For the past few weeks (in preparation for the poetry workshop I’m running on Saturday) I’ve been staring at images of Jean-Michel Basquiat, beautiful trickster in his customised football helmet, or with his dreads standing on end like Mickey Mouse ears, in his paint-splattered Armani suit, or posing next to his surrogate father Warhol. I’ve been staring at reproductions of his paintings in books, canvases littered with the stuff in his head: skulls, lists of jazz greats, cartoon characters, da Vinci-style machinations, fragments of poems, SAMO© graffiti, cereal packets, etc, etc. I’ve been looking at those images – of him, of his paintings – for years, and I’ve been trying to work out what keeps drawing me in…

Read MoreDemolition job

As I write, the remains of the upstairs bathroom are being removed from my house in chunks, the builders having taken a mallet to it. It is the norm around here in leafy Stockwell, where skips and scaffolding are a regular occurrence in our endless need to remove the vestiges of previous inhabitants and their now-antique ways, to ‘improve’…

Read MoreBaselines

As a poet, I am always interested in what artists do with text, and how, once fixed in a piece, if that text retains / contains meaning, or if meaning is obscured in some way, or lost completely. At Basel this year (my first outing to the annual art fair), there were a number of artists playing with notions of found text / collage. In the first of a series of posts on the fair, I want to focus on the humble postcard – a source for several artists.

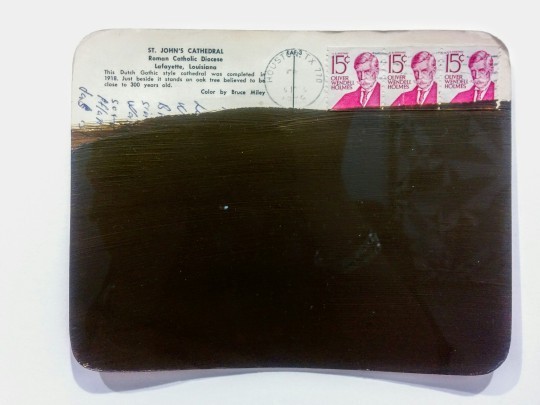

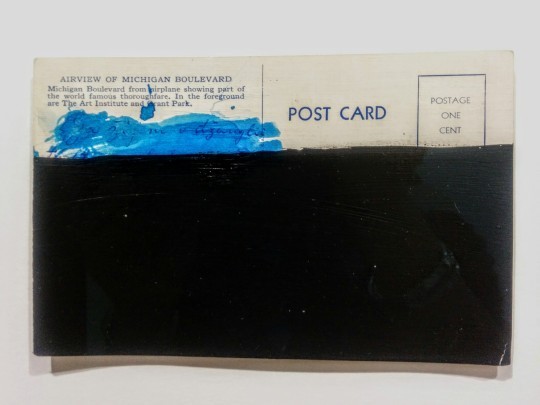

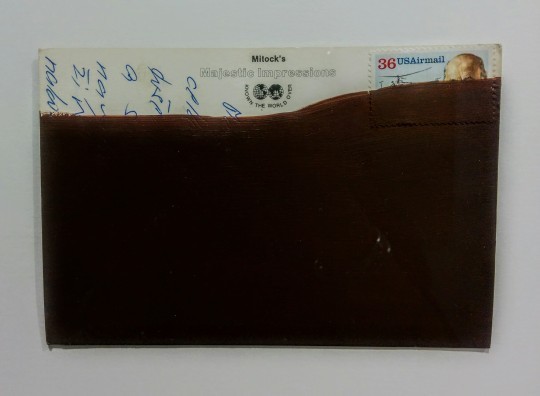

Roman Ondak is an artist concerned with process and record. I remember experiencing his installation at Tate St Ives some years ago, where he asked visitors to mark their height on the gallery wall with a pencil, then write their name and the date. The wall became an abstract drawing, a fluctuating line that looked like a tide marker (appropriate situated next to the sea). In his new piece, Messages, shown at Basel by Galerie Martin Janda, Ondak has taken a series of postcards, and redacted the writing with a sweep of heavy dark acrylic, leaving just a tantalising unreadable mass. The dark blocks are (again) like a tide consuming the text, something solid, oppressive – a tumour, a tomb. By choosing to show the cards text-side up, and then obliterating the greetings, we are left not knowing what the image is on the other side, or what the sender wanted to say about it. We are given clues – sometimes the printed text at the top reveals the location, and Ondak has preserved the stamps (I see him as a bit of a closet stamp collector); we can see all the cards shown in this selection originated in America – and weren’t sent yesterday. So notions of time, and how the past is obliterated, enter into the piece.

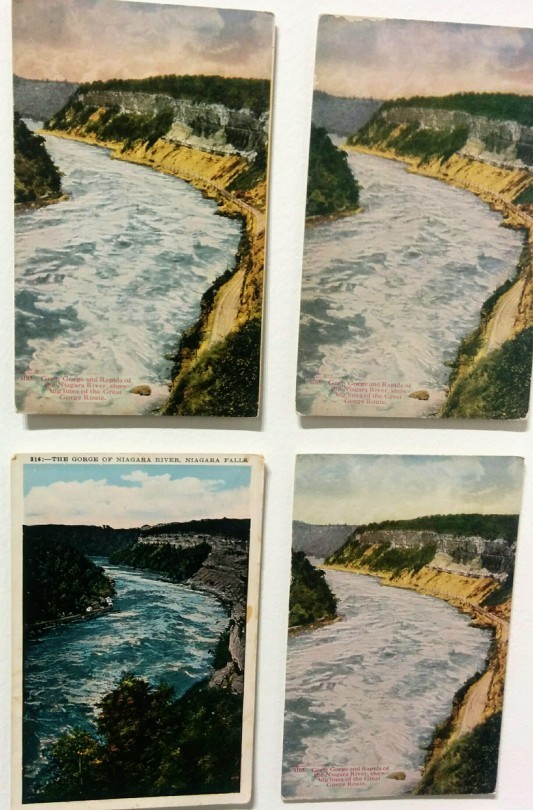

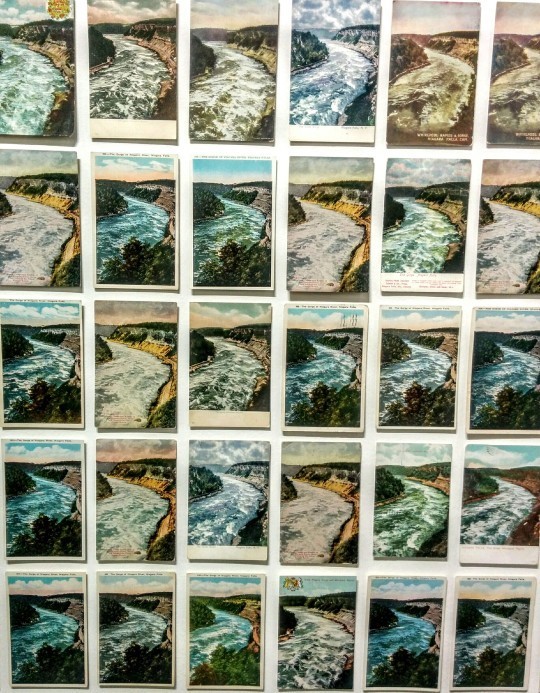

Zoe Leonard is an artist who is new to me, but looking at her other work online, she is predominantly interested in photography, exploring a theme exhaustively through a series of pictures, found and then pinned to the gallery wall. In her installation, The Gorge, on the Hauser and Wirth stand, she presents 240 postcards, all depicting a single location, the Gorge at Niagara Falls. Like Ondak’s cards, these are the kind you find stacked in boxes in antique shops, the senders and recipients long dead (and because the cards are presented face-out, we can only guess if they have been written on).

There is something both obsessive and detailed about looking at a whole wall of these, the cards often showing the same image, a body of water swirling towards a central whirlpool, like someone has pulled the plug in a bathtub. The textual element comes in the identification of the site – the font suggesting the cards are from the 50s and 60s (in addition to their faded quality). Niagara, of course, is famous as a honeymoon destination, a place of natural beauty, a tourist attraction. It sits on the border of two countries, America and Canada. It is the site of hydroelectric plants that provide power for both nations. Blondin the magician walked across the falls on a tightrope, carrying his manager on his shoulders. Marilyn Monroe and Joseph Cotton starred in the eponymous film, the strapline for which was “a raging torrent of emotion that even nature can’t control”. But there is something in the repetition that quells the torrent, creates a sense of boredom, flattens the drama.

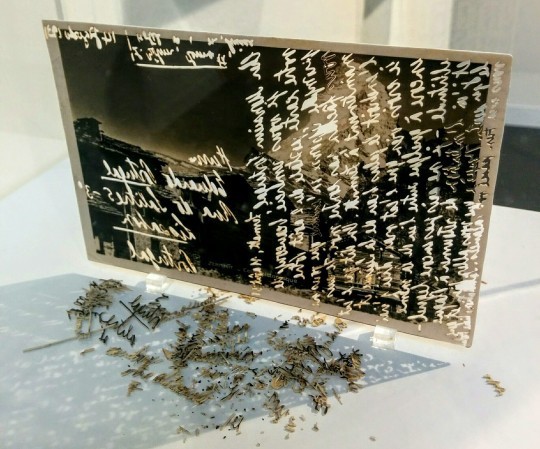

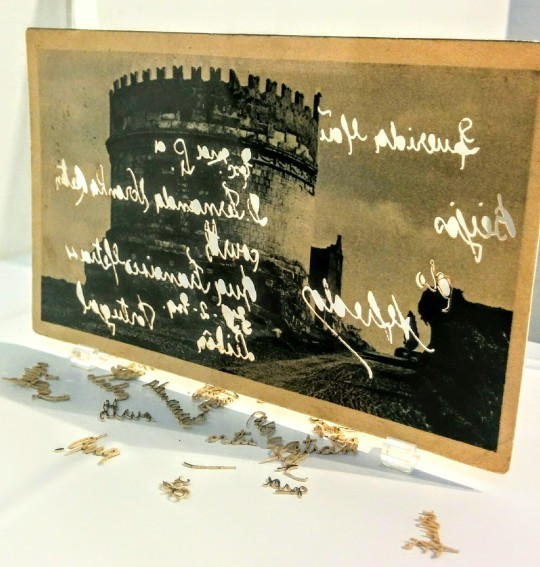

The Portuguese artist Carla Cabanas, showing at the Carlos Carvaho Gallery, takes a different approach. Her postcards become sculptures, mounted (so that the viewer can see both sides) inside a perspex box. The handwriting on each card has been carefully sliced away, letter by letter, allowing the cut-out letters to fall onto the box’s white floor. The scattered cuttings suggest some kind of damage, as if a letter-eating worm has attacked the browned surface (as with the other artists, Cabanas chooses antique postcards). Or perhaps they are a kind of extension of the image; one card depicts a little cabin at the foot of white-capped mountain, the letters like a snow drift. Although this ‘letter slicing’ preserves the text, it is still difficult to read; but I think it’s Cabanas’s way of tracing the hand that wrote the card, repeating the slow and deliberate action of writing, becoming the sender, speaking another voice.

What all three artists create with their found postcards is stasis – these rectangular vistas, written in one place and sent to another, are now halted, made into something else. The messages they transmitted have been hidden, so they are no longer vehicles of communication – just the opposite. Still, we understand what they mean, how we send them to people who are absent, with the familiar ‘wish you were here.’

One little room = an everywhere

The metaphor of ‘poem as room’ is a common one – indeed the word stanza comes from the Italian for ‘a room or standing place’. A poem is self-contained; you can think of its walls as the white area around it. It occupies a space – on a page, in a book, and the dimensions of its words contain a music that can be played with the voice, as well as meanings that connect the external experience of print with the internal experience of thought and feeling. A poem explores the interior world of human beings, and in turn we live inside interiors – between walls, hidden from others, in spaces we build to hoard our privacy. Homes are structures, just as poems are structures.

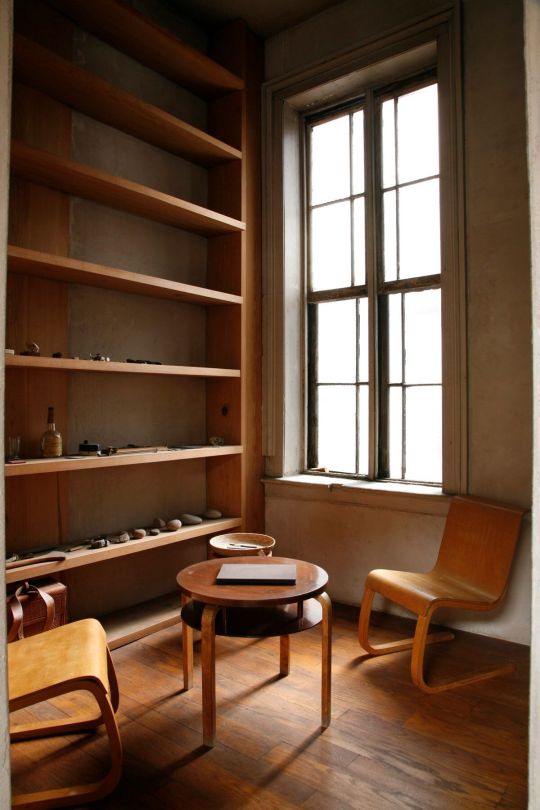

I was thinking of these connections again when visiting 101 Spring Street, which can’t simply be described as Donald Judd’s home and studio. 101 Spring Street was Judd’s first great experiment with structure. Walking through its vast open spaces now suggests these questions: how does someone live inside a building? And if that someone is an artist, how does he pay attention to what he places around him? How does that placement affect what he then makes?

In 1968 Judd purchased a five-story cast-iron building on the corner of Spring and Mercer in Soho. At the time, you could buy a whole warehouse around there for a song (Judd paid $68,000, money he’d acquired from an artists’ grant), as the surrounding streets were still pretty rough. But artists, always the front guard of urban renewal, could see the potential in those huge open spaces with enormous windows that let the light in.

In his 1989 essay 101 Spring Street, Judd outlines his ethos for the restoration of the building, which he found in a terrible state:

The given circumstances were very simple: the floors must be open; the right angle of windows on each floor must not be interrupted; and any changes must be compatible. My requirements were that the building be useful for living and working and more importantly, more definitely, be a space in which to install work of mine and of others.

(Here is a link on Places Journal to the essay in full: https://placesjournal.org/article/101-spring-street/)

What Judd created was building as sculptural installation. He took into account the proportions of the rooms, the height from floor to ceiling, and carefully considered where to place each object so that it might enter into a kind of dialogue with the building. That consideration moved from modest bowls and books, to tables and chairs (eventually, Judd would expand his practice into furniture making, perhaps as a way of exploring this issue) – to the intense light sculptures of his great friend Dan Flavin, and other art works, including a beautiful twisted wreck of car parts by John Chamberlain, and of course his own geometrical exercises in aluminium.

Judd and the artists of his generation were thinking about industry – how men forge in heat the shapes that contain us – right there in Soho, where the history of manufacturing began, and how to translate that into art. One reason Judd fell in love with 101 Spring was that it was made of cast iron, a material men have been using to make things since 5th century BC, when the Chinese produced cast iron pots.

I often think words have the look of something forged on the page. In letterpress printing (which involves hot metal press techniques), the words ‘bite’ into the paper, and you can see the mark of a word’s ‘teeth’ around it. Poetry in particular – as we’ve already said, the poem provides its own frame – the white field it occupies.

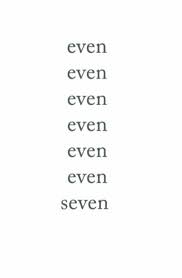

Here is a poem by Aram Saroyan, which I love for its simplicity, its basic mathematical pleasure, but also its architecture – its tribute to the classical perfection of columns. It plays with the known rules of grammar – if the ‘s’ added in the final line were at the end of the word, it would suggest plurality (but it would also tell a numerical lie, as seven is not an even number) but at the beginning, it simply tells us how many times the word ‘even’ has been repeated, while continuing the repetition. Saroyan was writing concrete poems (even the term nods to its architectural properties) like this one at the same time Judd was first pacing the floors at 101 Spring Street; Saroyan points to Judd as one of his influences. He said Judd’s work ‘balances the environment’; I love his balancing act with words. They are surprisingly solid.

In 1986, Judd wrote: A definition of art finally occurred to me. Art is everything at once. Insofar as it is less than that it is less art. In visual art the wholeness is visual. Aspects which are not visual are subtractions from the whole.

It seems to me that’s what happens with poems too. Saroyan’s structure is perhaps an extreme example, but if you try to remove one word (like in Jenga), you risk the whole thing toppling. I left 101 Spring Street thinking about form, and how important it is in making things, anything really – sculptures, buildings, pots, poems – and how difficult it is to achieve. And how Judd spent his whole life looking and experimenting, and retained the patience to keep trying.

With my thanks to the Judd Foundation for their permission to reprint the photographs of 101 Spring Street included in this post.

Charlie Rubin. 2nd floor, 101 Spring Street, New York, NY.

Joshua White. Exterior, 101 Spring Street, New York, NY.

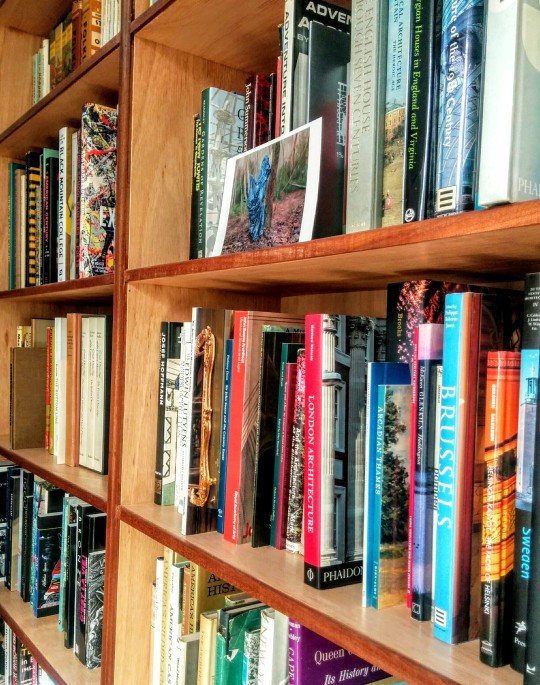

Mauricio Alejo. Library, 3rd floor, 101 Spring Street, New York, NY.

All images © Judd Foundation / Artists Rights Society (ARS)

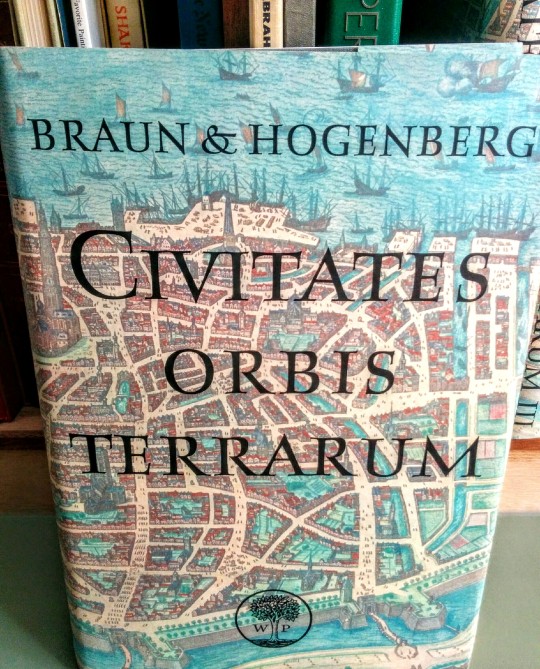

Unpacking a library

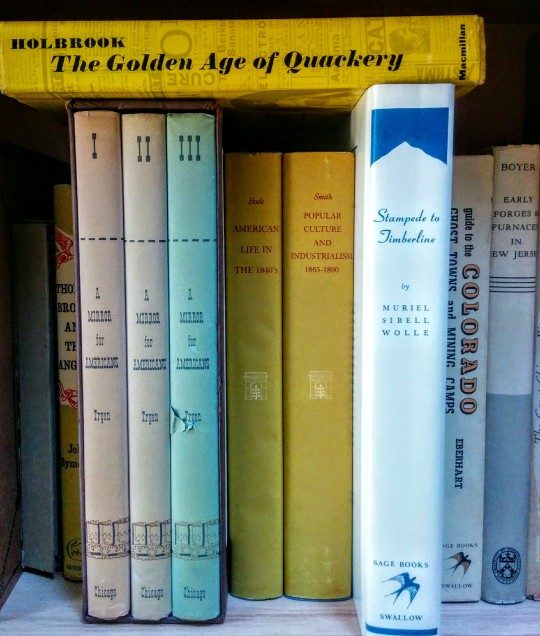

After my father died in 2007, I put what was left of his library in storage. It’s hard to say how many books he’d had originally, maybe 10,000. He started his career as a publisher when he was in his early thirties, and so the books he’d seen into the world formed a large part of the collection, as well as books from fellow publishers, authors who were also friends, books on subjects that interested him – American history, philosophy, literature, Judaica. When I was a child, I used to spend hours in the room that contained his library. It was separated from the main body of the house by a glass patio – as a result, it was always a few degrees colder than in the rest of the house. That cold air has stayed with me, as if each time I open a book, it gives off a puff of breeze to wake me up.

I find it difficult now to remember other rooms in my childhood house – I must have spent more time in the kitchen, which was at the other end of the patio, but I can’t recall much about it, apart from a hazy notion of its layout. But I can picture the library as if I’d just left it, even the smell. Gaston Bachelard says:

We comfort ourselves by reliving memories of protection. Something closed must retain our memories, while leaving them their original value as images. Memories of the outside world will never have the same tonality as those of home and, by recalling these memories, we add to our store of dreams; we are never real historians, but always near poets, and our emotion is perhaps nothing but an expression of a poetry that was lost.

I took that idea of my father’s library as a protecting space, cut off from the rest of the house, as a image to begin this poem:

The Library

The fire was never lit. Cold, her body

was alert to words, her pores open to knowledge.

Sealed off from the rest of the house, padded

with paper and board, the only sound was the turning

of the page, a whisper, her shallow breath.

Gone. The books scattered to far corners,

cities a thousand miles away, strange

against paperbacks with rainbow covers,

they still carry the scent of deerskin and beeswax,

mildew—travellers from an antique land.

The model ship that used to drift the dark oak desk

is lost, never to reach the new world,

never to return home. She would touch

its windless sails, wonder at how they could make

everything so small. A planet reduced.

As my parents downsized, so did the library’s holdings. Finally the last two thousand or so books were boxed and removed from my mother’s house in West Windsor, her final US address before she moved to London, where she lived for her remaining five years. After navigating the Atlantic, the books landed in a warehouse in Bury St Edmunds, in huge crates (I went to visit them once in situ, and was reminded of the final scene in Citizen Kane). And now they have found a new home, mingling with their much younger companions – the books I’ve assembled over the years.

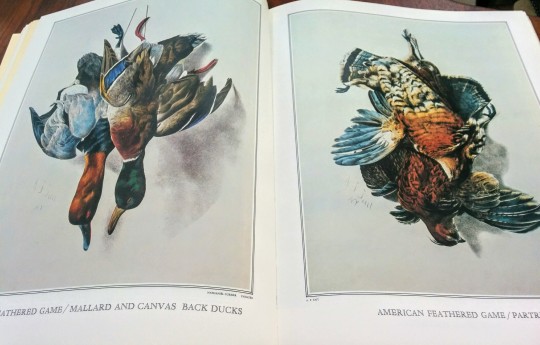

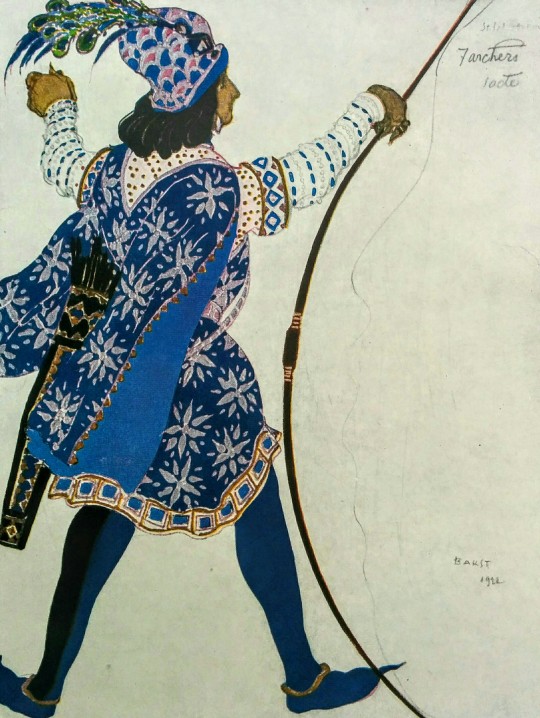

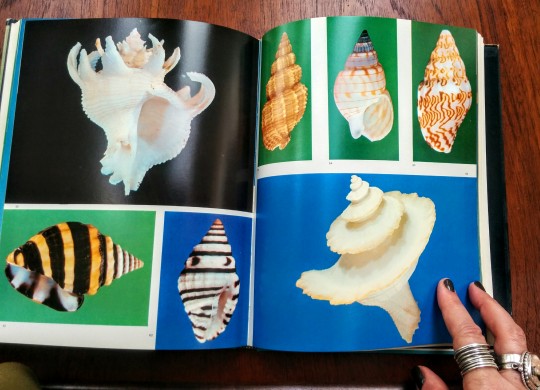

This is just a small survey of my father’s library. Books on type design, on Russian theatre, on sea shells, oversized atlases and surveys of Currier and Ives and Audubon prints. I am now their keeper.