As we are getting used to Zooming in on each other, I have become fascinated by the pictures people have on their walls. Last week when Matt Hancock gave a virtual Coronavirus briefing, he chose to stand in front of a Damien Hirst spin painting depicting the Queen, donated to the Government in 2015. Was that Hancock’s way of saying he has his finger on the pulse, that he’s both traditional and contemporary? Or were advisors simply trying to find an image to appeal to the beleaguered nation – while drawing attention away from a man who is very clearly unsuitable to the current challenge?

As so much of this blog has been dedicated to visiting art in other places, I thought this would be the ideal time to talk about the pictures on my own walls, which, although I see them every day, I perhaps don’t examine in such detail in busier times, and to consider what they say about me.

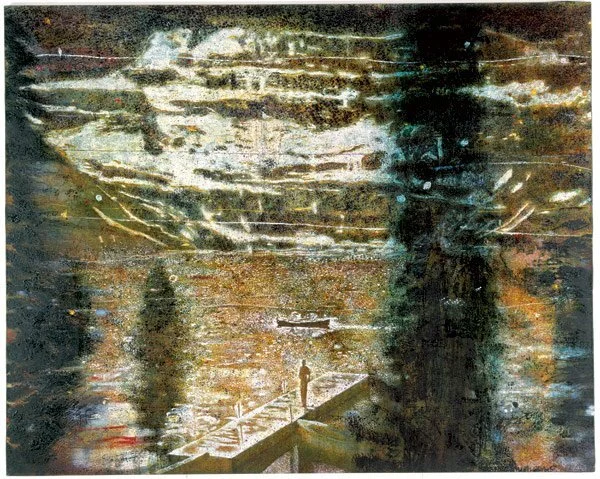

I bought the lithograph by Peter Doig shown above at an art fair twenty-five years ago, part of a portfolio series. It’s from Doig’s pre-Trinidad period; I’ve always responded to the sombre mood of his earlier works more than his bright Caribbean landscapes. Doig grew up in Canada, and so his frame of reference is similar to mine – his snowy landscapes were based on actual childhood places, but also on the densely-wooded mazes of 70s horror movies, such as Friday the 13th. I watched those movies too (sometimes hiding my eyes just as the axe made contact with its victim) which made my excursions into the wildernesses of New Jersey even more thrilling. Nature was real, and on the doorstep, but also mysterious. I’ve written before about my habit of hoarding nests and bird skulls and odd-shaped stones – something I do to this day. No matter where you end up (I think of myself now as an urban dweller) your early formative landscape is the one that remains with you. I see my own childhood in Doig’s woods and lakes and pines.

The filter of memory gives the picture a sepia tint like an old tintype, but that particular brown also screams 1970s: forest holiday cabins, ranch-style restaurants, Lincoln Logs, hand-tooled cowboy boots, simulated wood-grain panels on the sides of station wagons. It’s also the brown of old masters, which gives it the look of a renaissance pen and ink drawing.

The contrast to those modulations of brown is white. More often than not, it’s snowing in Doig’s Canadian landscapes. It snows a lot in Canada, as it did in New Jersey when I was growing up. Here the snow is a polka dot pattern laced through the sky, reflected in the lake. This is a child’s drawing of snow, depicted in great globes of white, more like stars or planets suspended in the sky. It’s like Currier and Ives on acid. When it snows now, it’s never as exciting as it was when I was a child, and the snow was just the way Doig shows it – brightening that brown veneer of boredom.

In this picture, I can travel not only to these silent woods, but back in years. It is a place of calm. I don’t feel a sense of dread despite the filmic source; Doig’s sites are backdrops, landscapes devoid of their human elements. When he does introduce a figure, he is always alone, miniscule in the vastness of the towering trees around him. In that sense, his Canadian landscapes are the perfect vision of peace for us in our isolated times.

Peter Doig, Jetty, 1994