I have spent the last couple of weeks in and out of the Hayward Gallery, in anticipation of the Poets After Dark event in April. I am one of the ‘dark poets’ – ten of us in total – commissioned to write a new poem inspired by the Hayward’s current exhibition, Light Show. The exhibition brings together artists who work with light in various ways: there are minimalist works from Dan Flavin, an immersive piece by James Turrell that plunges you into darkness and then confuses your concept of space, a wild strobe-lit ‘night garden’ by the Icelandic artist Olafur Eliasson, Katie Patterson’s single bulb which simulates moon glow, Leo Villareal’s waterfall cascade of LEDs. The overall effect is to remind us how light (and sometimes the absence of it) effects our moods and minds, and of course, how technology (sometimes very simple or antiquated) creates the ability to make work that moves and changes before our eyes like a magic trick. The whole show is about magic, and illusion, and disorientation.

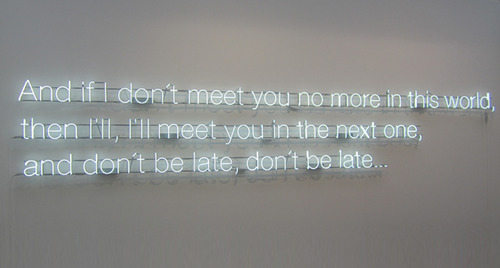

But even before I went round, I had an idea of which piece I would choose. I have been a fan of Cerith Wyn Evans’ work for some years now, and when I discovered that the piece for the Hayward took as its starting point a line from a poem by James Merrill, it seemed the natural choice. Merrill’s line, ‘Trace me back to some loud, shallow, chill, underlying motive’s overspill’, is from the epic poem The Changing Light at Sandover, a 500-plus page formal exploration of his experiences with his partner, David Jackson, summoning spirits through the Ouija board. In their years of occult searchings, they managed to contact Auden, Yeats, Maya Deren and a Roman sage named Ephraim, to name a few. These voices appear throughout the poem as dramatis personae, and serve to guide, and sometimes chide, their mortal hosts. The overall effect is impressive, if not bonkers. One might dismiss Sandover as eccentric (if not formally accomplished) ramblings, and quite a bit of it is. But it also serves as a vehicle to record Merrill’s thoughts about mortality and afterlife, and the here-and-now life he led with Jackson. In ‘The Book of Ephraim’, Merrill talks about ‘one floating realm’, the other world, as opposed to ‘one we feel is ours, and call the real.’ And within the real, momentous events occur, which the poet attempts to process:

We take long walks among the flying leaves

And ponder turnings taken by our lives

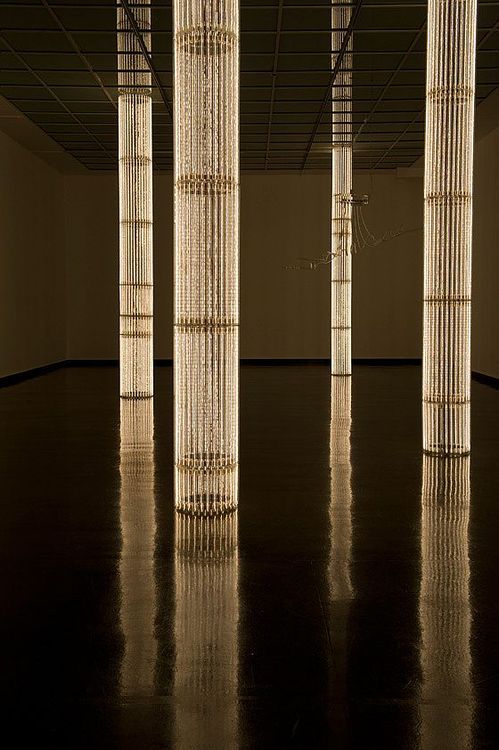

Wyn Evans’ piece is not about this realm – the real, so much as the other – the floating. The work comprises three standing columns made out of obsolete incandescent strip lights, the harsh lightscape of classrooms and public-sector offices. Wyn Evans says of these columns: ‘They are in suspension, between heaven and earth. They have a life of their own.’ Indeed, they do – I have spent several hours sitting in their presence, watching then flare to light, and to heat (suggesting the presence of the physical body) then fade, with a bluish quivering after light, into cold darkness. The effect is haunting, moving. I can sit for some time, not writing, just watching their hypnotic movement (and watching other gallery visitors approach them, holding out their hands to catch their warmth, as if they might embrace them). I’ve jotted down a few lines in my notebook in an effort to try and work out what I think they are: columns, circles, towers, amusement arcades and how they work: elements, visible wires, like a magic trick exposed.

My poem is forming itself slowly. It started with a line from Merrill, which I’ve now removed, as he felt too strong a presence (perhaps like his Oujia board party guests), although Merrill seems to be hovering over it, a benign ghost. It feels like a slow unravelling, which is perhaps appropriate for the vastness of the subject. One line of Merrill’s stays with me:

A whole small globe – our life, our life, our life.

Information and tickets for Poets After Dark here:

http://www.southbankcentre.co.uk/whats-on/poets-after-dark-70624