Staphorst is a place you can’t quite place. I was expecting it to be rural, and it is, in a way. We travelled on three trains to get there; from London to Brussels, Brussels to Schiphol. And from Schiphol, heading north, through Rotterdam, towards Meppel; the landscape eventually yielding to wide, flat fields separated by irrigation canals and lined by rigid rows of poplars, with the odd farmhouse or windmill suggesting habitation. But once we had alighted from the train, I was surprised by the amount of traffic. While some of the older women still cycle on ancient pushbikes in traditional dress, there are a lot of cars for such a small town, all heading in convoy to low-built strip malls along the main street. In that respect it reminded me of suburban New Jersey. But the long farmhouses with their painted shutters and thatched roofs brought me quickly back to Holland. None of the houses along the main road are particularly old; although they resemble seventeenth-century dwellings, most were built in the early part of the twentieth century, giving the town a feel of a restored village (again, I thought of America, somewhere like Williamsburg, although Staphorst is not a tourist recreation – this is how people live). The farmsteads grew up in a straight line along the bog; a farmer’s son would build his house behind his parent’s house, and his children behind him, so all the houses are regimented along the main road, facing the same way. There are cows and sheep in the yards, milk pails hanging along the wall, thatched sheds in the back. It is considered to be one of the most religious places in Holland. The town falls silent on Sundays.

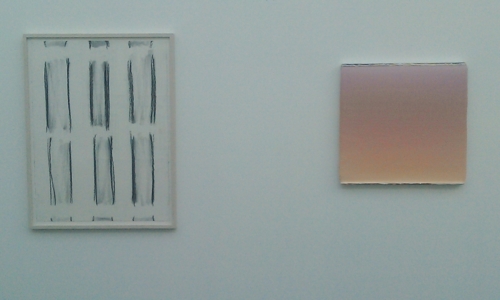

It is an odd place then to find an exhibition of contemporary art. But just on the outskirts of town, Hein Elferink has built a gallery next to his house. On the Saturday we were there, light was streaming through the large horizontal glass roof, and we could see the brown forms of winter trees crowding the sky. We were gathered for the private view of works by Linda Karshan and Marian Breedveld; Linda’s drawings, as always, stark in the best possible way, like charts to nowhere, next to Marian’s bright swipes of colour. They worked surprising well together, matched in their sense of pattern and motion (Linda and Marian discovered they had a common background in dance which informed both their works).

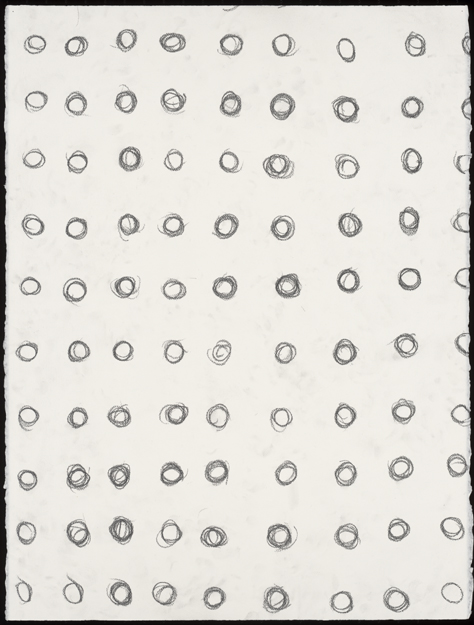

It was also the launch of Desire Paths, the edition of Linda’s new woodcuts and my corresponding poem. It is a beautiful production; the sheets emerging from an earth-coloured box, Linda’s woodcuts on delicate tissue-thin Japanese paper, but dark, grained, serious. My poem like an inscription carved in stone or on a tomb. Amazing to think that although Linda was in Connecticut, I was in London and Hein was in Staphorst, the finished result of our project is completely, stunningly integrated. Our paths finally came together, making the title of the work more relevant.

But this is what Hein does. He shows us his presses, his cases of metal type: Fournier (which is the font chosen for our edition), Baskerville, Gill Sans, Bembo. Classic faces. The paper he uses is thick and smooth, a creamy off-white. His boxes are covered in linen, the bindings hand-stitched. This is slow, meticulous work. The book as artifact, as artwork.

So maybe not so odd then, to be in Staphorst. The town is famous for its ‘stipwork’, a traditional kind of button embroidery that decorates caps and skirts. It is a place where people make things with their hands, the way they’ve been making things for years. There is devotion and patience in this kind of making, just as there is devotion and patience in making books, and pictures, and poems …