In 1905 the Austrian author Stefan Zweig wrote an essay describing the summer season in Ostend, which was then the North Sea’s answer to Monte Carlo. He speaks of the elegant women promenading on the front, the delicate art nouveau architecture. Zweig was in Ostend when Archduke Franz Ferdinand was assassinated in 1914, heralding the beginning of WWI. The Germans were to capture the port, as well as most of the Belgian coast, the following year. Although Ostend suffered extensive damage, ‘La Reine des Plages’ made a comeback as the premier jazz age resort of Northern Europe. But WWII was to bring greater destruction and an end to the concept of the ‘summer season’. It is a place that represents a way of life which no longer exists.

The Ostend you see today still retains traces of its glory, in blocks of Deco flats skirting the Digue like ocean liners, in sweeping Horta balconies above betting shops and chain stores. It is like so many once-grand British seaside resorts; but where places like Blackpool survive on kitsch, and Folkestone and Margate attempt to reinvent themselves as art destinations, Ostend strikes me as irredeemably depressing.

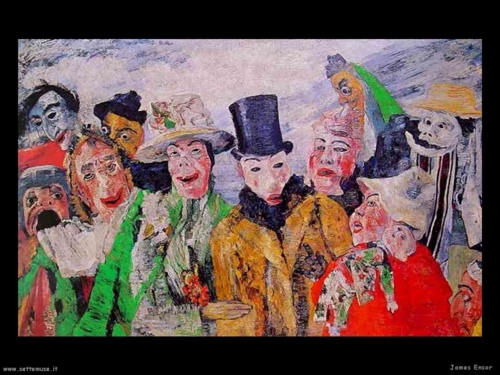

I suspect the Flemish day-trippers around me don’t share my view. On a slightly overcast August Saturday, they come pouring off the train, groups of girls tottering in skyscraper heels ready to hit the shops, and men with tattoos and cans. They remind me of the hoards that pack the sandy beach in James Ensor’s drawings (modern-day versions of Breughel’s village scenes). Ensor is the most famous son of Ostend; an artist who remained faithful to the place that gave him his vision. He would have seen it in its heyday, and watched its decline. He never decamped to Paris or the States; although by the end of his life he was famous (the Belgian government made him a Baron). He stayed in Ostend, in a flat over the souvenir shop his mother ran selling carnival masks and shells. After his death in 1949, the shop and flat were opened as a museum. It is his museum that has brought me here.

I have been a fan of Ensor’s work for nearly 30 years. He is like no other artist, in his mix of the figurative and the surreal, the broadly comic (which comes from his Flemish roots; but also from his English roots, and the tradition of Hogarth and Gilray) and the morbidly serious. Here is a world of colour and carnival, but in the centre of it, death and loneliness. In his greatest work, the monumental ‘The Entry of Christ into Brussels’, the tiny figure of Jesus is isolated, alone, almost lost (like ‘Where’s Wally?’) in the tapestry of humanity cramming the streets. The reason for the celebration becomes sidelined by the desperate need to be part of the crowd.

To be honest, the house is an enormous disappointment. There is something shabby and sad about the place. Screenprint reproductions of his paintings line the walls, the real thing shipped to grander galleries (his paintings ended up seeing the world the artist never visited). There is his harmonium, the easel where he painted, but in the dark Edwardian gloom, it is impossible to see how anyone could be inspired.

Unless of course your message is all about isolation, like that tiny figure no longer central to most people’s lives. The masks the artist’s mother sold from the downstairs shop keep appearing, as if you could change your identity, become someone else, by wearing one. Skeletons dance and put on frilly hats, but they are there as a reminder. He lived here all alone for the last third of his life, and watched the world change from one tiny lace curtained window.

Ostend speaks to me of failure. A place of grandeur struck down by one war, which lifted itself up, only to be practically leveled by another. And now it has given up. While I stand on the Digue, looking out over the sea towards England, riots are brewing in London, which will spread, like the fires the rioters light, to other cities. I wonder what Ensor would have made of the world now.