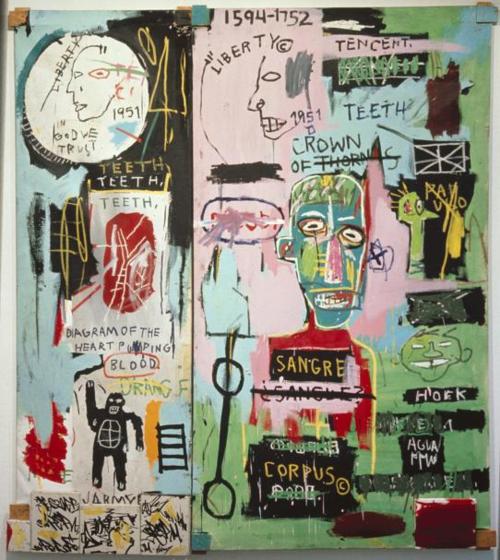

For the past few weeks (in preparation for the poetry workshop I’m running on Saturday) I’ve been staring at images of Jean-Michel Basquiat, beautiful trickster in his customised football helmet, or with his dreads standing on end like Mickey Mouse ears, in his paint-splattered Armani suit, or posing next to his surrogate father Warhol. I’ve been staring at reproductions of his paintings in books, canvases littered with the stuff in his head: skulls, lists of jazz greats, cartoon characters, da Vinci-style machinations, fragments of poems, SAMO© graffiti, cereal packets, etc, etc. I’ve been looking at those images – of him, of his paintings – for years, and I’ve been trying to work out what keeps drawing me in…

Read MoreJean-Michel Basquiat

To repel ghosts

I am staring at the iconic photograph of the late artist Jean-Michel Basquiat by Lizzie Himmel, the one where he is posed on a red leather chair in his studio. Painted directly onto the wall behind him is a lumpy black figure, part cartoon, part gremlin, with bared teeth. Gremlin and artist are facing each other. Basquiat is wearing a pinstripe suit and a tie, but he is clearly artist rather than businessman; the cuffs of his trousers are dirty, he is barefoot. One foot is propped against a toppled chair. He holds his paintbrush aloft. It is 1985 and he is at the height of his fame. Three years later he’ll be dead.

The photograph is blown up to fit the wall so that he is larger than life, confronting visitors arriving at his Musée d’Art Moderne retrospective. People are streaming into the museum to see his work; they are photographing his photograph, posing in front of his image. Mostly young girls; too young to remember him. But he is forever 25 years old in this photo – cocky, beautiful, haunted. If he had lived, he would have been 50 this year.

As I am walking through the show, I’m thinking about Jackson Pollock. Not necessarily the first artist you might connect with Basquiat, but since I’ve been immersing myself in Pollock’s life and work for the last few months, he is never far away. They were both ‘untrained’ talents. True, they both went to art school, but what they created was not something that was taught to them. Both were undisciplined, liberated, self-destructive, and what they brought to their art was an expression of chaos, the world turned on its side. If Pollock had lived, he might have admired the young Basquiat, from the perspective of the older artist who had ‘been there, done that’.

Basquiat’s world is bright and throwaway, but there are always gremlins and ghosts in the background, random scrawls crossed out, eradicated. He is often referred to as a graffiti artist, but the graffiti here are the jottings of the psyche, the ‘heart as arena’. These jottings link him most closely to Twombly, but the latter artist had a greater library from which to draw, quoting Rilke and Keats on his canvases. Basquiat’s references mix the high and the low; the language of billboards and ad campaigns merged with snippets from Greek myth, the names of gods and kings (which makes me think of O’Hara at his best, as in ‘The Day Lady Died’). The texts in Basquiat’s paintings give the viewer a way to read his mind. In Eroica II, one of his last paintings, the images disappear completely and the canvas is given over to words; a litany of ‘b’s from a slang dictionary: ‘balls: testicles / bang: injection of narcotics or sex / bark: human skin’. It is as if his gremlins are speaking directly to us, mischievous and deathly in the same breath. On the side, the phrase “man dies”, written in shadowy grey. In the end, he was not able to repel his ghosts.