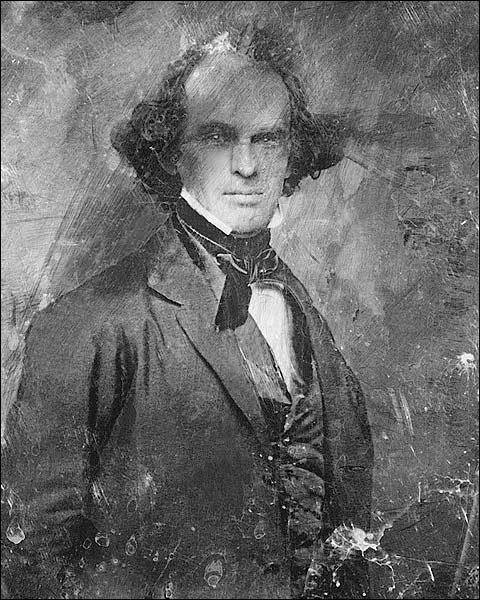

The novelist Nathaniel Hawthorne served for four years as US consul in Liverpool. During his time in England he wrote the following:

The years, after all, have a kind of emptiness when we spend too many of them on a foreign shore. We defer the reality of life, in such cases, until a future moment when we shall again breathe our native air; but, by and by there are no future moments; or, if we do return, we find that the native air has lost its invigorating quality, and that life has shifted its reality to the spot where we have deemed ourselves only temporary residents. Thus, between two countries we have none at all, or only that little space of either in which we finally lay down our discontented bones.

My mother used to carry this quote inside her wallet, which is when I first came across it, long before I had myself become an expatriate. My mother would not have known when she cut it out of ArtNews Annual in 1966 (where it was in turn quoted by John Ashbery in an article about American painters in Paris) that she was to spend the last five years of her life in London. But something attracted her to Hawthorne’s words, perhaps a sense that she was in some way an outsider, especially during her childhood in Newburgh, New York. She found the invigorating air Hawthorne talks about in Manhattan, a place (with a Native American name) that doesn’t really belong to America, international and cosmopolitan as it is. And I found that invigorating air in London, so I’ve never really believed Hawthorne’s assessment. For years now I’ve maintained that I become more foreign each time I return to the US, and to a certain degree this is true. My accent puzzles people, they can’t place me, can’t work out where I’m from. But in my 28th year as a Londoner, I feel as if Hawthorne’s words are pertinent, and I am going through an identity crisis.

This came to the fore during my visit to SUNY Fredonia, where I had been invited to give a talk and a reading of my work. The students seemed especially curious to know how I ended up in London (most of them were around the age I was when I left the US), if I found British words and expressions creeping into my work, if I thought I had a different view of London than those who’d been born there. During the reading I found myself darting between New York (I read a number of poems from my Jackson Pollock sequence) and London (characterised by Vici’s Formerly photographs). London is my home now, but there is something that continues to draw me to my birth country, especially now that the ties I have to it are increasingly diminishing.

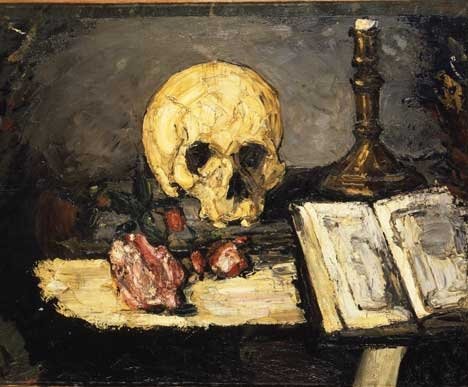

My father would have been 100 earlier this month. I started my trip at his grave, with a copy of Christina Rossetti’s Selected Poems, a stone to lay, and some of my mother’s ashes to scatter. Rossetti has been a poet very much present for me over the last few months. If Rossetti has a ‘theme’ (and I believe most poets do) it is mortality and remembrance. It has struck me powerfully in recent days that once someone is permanently gone from your life, your memories are all you have left; selected and constructed from life, but still edited highlights, and therefore often unreliable. I have always loved this poem by Sheenagh Pugh, which for me captures perfectly this condition:

Times Like Places

There are times like places: there is weather

the shape of moments. Dark afternoons

by a fire are Craster in the rain

and a pub they happened on, unlooked-for

and welcoming, while a North Sea gale

spat spume at the rattling windows.

And most August middays can take him

to the village in Sachsen-Anhalt,

its windows shuttered against the sun

and a hen sleeping in the dusty road,

the day they picked cherries in a garden

so quiet, they could hear each other breathe.

Nor can he ever be on a ferry,

looking back at a boat’s wake, and not think

of the still, glassy morning off the Hook,

when it dawned on him they didn’t talk

in sentences any more: didn’t need to,

each knowing what the other would say.

The worst was Aberdeen, when they walked

the length of Union Street not speaking,

choking up, glancing sideways at each other,

but never at the same time. Black cats

and windy bridges bring it all back,

eyes stinging. Yet even this memory

is dear to him, now that no place or weather

or time of day can happen to them both.

On clear winter nights, he scans the sky

for Orion’s three-starred belt, remembering

whose arms warmed him, the cold night

he first saw it, who told him its name.

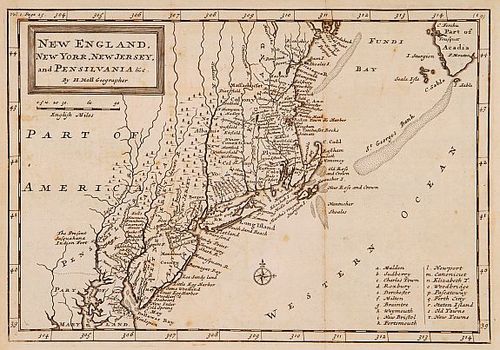

It is that idea that place, as much as the people who occupy it, also vanishes with time. With this in mind, my husband and I took a drive through Colts Neck, the small township in New Jersey where I spent the first seventeen years of my life. My mother had a framed picture of our house on her wall in London; the house is still standing, but it is much altered, and I found myself wondering if we had come to the right house, even though I knew for certain it was the one. I would have stayed in the car, but Andrew, curious about the place I’d talked about for years, got out and rang the bell. And someone was home, a woman who had lived in the house for the past 26 years, which immediately cheered me – someone loved it enough to invest a good portion of her life there. She asked if I wanted to have a walk around the grounds, and I said yes, even though part of me wanted to drive away immediately. What was strange was the sense of confusion I had in a place I thought I would always be able to navigate, as I knew every blade of grass. But that is because my childhood home has been sealed in memory, and in the land of memory, nothing ever changes. But the memory bank for the house closed thirty years ago, and in real time, much has happened, people have got on with their lives. I found the only way I could really navigate the familiar alien terrain was by certain trees that were still standing; many had gone. But I came away thinking that as much as I remembered, I was not remembered. The house was not sentimental, it would hold whoever occupied it, the same floorboards would creek under different feet. The windowsill in my old room where I’d carved my initials had been certainly painted over years ago.

In her years in London she missed America terribly, the familiar air. As much as she always loved London, her memory of the city stretches back to the early 50s, and the many years she came with my father. The London I live in was sometimes difficult for her, as most cities are when you are older. She used to love the towpath along the Delaware and Raritan Canal, where she walked for many years. As I walked the towpath for the first time in many years, I thought about why we love places, why they become important to us. Canals are interesting places, a man-made intervention in the landscape created to connect one body of water to another. Longtime Hopewell resident Paul Muldoon has written about the canal, making the connection between himself, the Irish poet living in America, and the Irish navvies who dug the canal (many losing their lives in the process) nearly 150 years ago.

My mother just thought it was a pretty place to walk. And it is – the long towpath separating canal from river, so you feel as if you are on a island, isolated from the busy world around you. But it is also a place of connections: land to water, water to water. She didn’t know she’d be making the long journey over the ocean so late in life. I realised as I scattered more of her ashes on the towpath that I was bringing her home, to her invigorating air.