I arrived in Spain just as the news was breaking back home of Seamus Heaney’s death. Earlier in the week, in preparation for my course, I had been reading ‘Summer 1969’ from ‘Singing School’, Heaney’s account of vacationing in Madrid at the very moment when civilian protesters were being gunned down by the constabulary on the Falls Road. Heaney’s inability to forget what is going on in his home while he is ‘suffering / Only the bullying sun’ leads him to a greater dilemma – what can he, as a poet, say to make a difference.

It’s the old refrain of Auden’s: ‘poetry makes nothing happen’, written on hearing the news of the death of Yeats. And the same cycle of suffering and inability, the effort (and possibly failure) to make a difference is present in his poem, which equally could be a statement on Heaney’s work (now complete):

Mad Ireland hurt you into poetry.

Now Ireland has her madness and her weather still,

For poetry makes nothing happen: it survives

In the valley of its making where executives

Would never want to tamper, flows on south

From ranches of isolation and the busy griefs,

Raw towns that we believe and die in; it survives,

A way of happening, a mouth.

Followers of Invective will know I have quoted those lines before. They never date – sadly, as I abandoned the news section of my paper on the plane, with its headlines speculating the possible American invasion of Syria.

Despite the Syrian crisis and the sad news of Heaney’s passing, I was glad to be back at the Almàssera Vella, with Christopher and Marisa North, who for part of the year generously open their home as a retreat for writers – a stunning place to gather and spend a pleasurable week in the sun (very hot, certainly, but more nourishing than bullying) talking about poetry and art. We were fortunate in our group to have two sculptors and a former artists’ model, so the discussion took on many aspects and angles. We started with Wallace Stevens’ ‘The Man with the Blue Guitar’, written around the same time as Auden’s tribute to Yeats, with the world on the brink of yet another world war; it’s tempting to see the two poets in dialogue, as Stevens presents his imperative to the writer or artist:

Throw away the lights, the definitions,

And say of what you see in the dark

That it is this or that it is that,

But do not use the rotted names.

How should you walk in that space and know

Nothing of the madness of space,

Nothing of its jocular procreations?

Throw the lights away. Nothing must stand

Between you and the shapes you take

When the crust of shape has been destroyed.

You as you are? You are yourself.

The blue guitar surprises you.

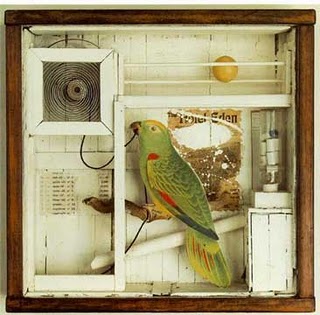

Stevens’s blue guitar is an instrument of invention, a metaphor for how we construct metaphor. Despite the destroyed shapes and rotted names we continue to try and make sense of the world, even if it feels sometimes as if no one is listening or looking. Stevens, of course, is the presiding spirit of this blog, and it’s his poetry I have often turned to as a model of how to construct my own. Like Heaney, Stevens is really talking about the world and the reality of the world, and how reality is sometimes bleak, but like Heaney, Stevens will guide rather than preach. His blue guitar, by way of Picasso and Braque, stands for the imagination, a reflection of us that isn’t us, but something that sings our pleasures and pain. We can’t change reality, instead we ‘patch’ the world as best we can; poet as invisible mender.

So round the table in the blue house, we sat talking about Stevens’ blue guitar, and Jorie Graham, Charles Simic, Frank O’Hara, the latter becoming another kind of presiding spirit for us. We decided to write a ‘lunch poem’ every day, although we had to trade O’Hara’s frenetic Manhattan for sleepy Relleu (the village going into siesta mode just as we were gearing up for our afternoon’s writing).

It was O’Hara who declared it ‘a fine day for seeing’, and when we piled into a couple of cars on the Tuesday, the sun still shining, we were more than ready to look at some art. We took a detour on the way to Alicante to visit a 2000-year-old olive tree, growing a few hundred yards from the motorway, down a dirt track. It was an amazing sight, its great, gnarled branches twisting up and into a canopy of small silvery leaves. Later, in the gallery when we considered issues of texture and complexity, looking at sculptures by Sempere and Chillida, we recalled the smooth wood of the olive, rubbed white in places, like bone – reality as metaphor, a symbol of stubborn survival.

The Museo de Arte Contemporáneo de Alicante is a revelation. Three floors of modern and contemporary art, mainly by Spanish artists, many who were new to us. The building itself is a sculpture – all white marble and stone, a clean space for seeing, a true meeting of architectural vision and user-friendly space, with balconies on the upper floors that open to vistas of the galleries below and to the hills and castle outside.

It is a symbol of pre-recession ambition and civic pride, all the more surprising in a town where most visitors head straight for the promenade and the beach; as a result, we had the place pretty much to ourselves (the museum attendants actually outnumbering us). It is incredible that more people are not taking advantage of this remarkable gallery (which offers free entry). The fact that there is no catalogue of the collection, not even a postcard or two, perhaps reflects its underuse. So we had to record our experience in our poems (and a few stolen snapshots).

The next day we piled back into cars and drove to the nearby village of Sella, and into the hills, the craggy puig molten copper in the late afternoon sun. We climbed higher and higher into the Tafarmach ridge, finally reaching the home and studio of Terry Lee and his wife Pam (who paints under the name Olivia Firth). We talked with them about their work, their notion of landscape; how we carry the landscapes of our past and of our imaginations with us (Terry often bringing together his adopted Spanish hillside and his native Derbyshire in the same painting). And I thought of Heaney again, how in his poem he can’t help think of the reek of the flax-dam as he passes through the fish market of Madrid, how he finds Goya’s cudgels in the Prado, and thinks of them as ‘two berserks’ who ‘club each other to death / For honour’s sake, greaved in a bog, and sinking.’ The visit to Terry and Pam, to the remote and extraordinary landscape in which they live and work, was an inspiration to us to think about how we might make space for our work, even in the noisy corner of a busy city.

And all too soon it was time to return to our respective cities and cloudier skies, away from the dreaming space of the Almàssera. But many poems are still to be written, as we carry the landscape in our minds, one more folded sunset.