To Middlesbrough, for my workshop on Poetry and Memorial, occasioned by Julian Stair’s extraordinary exhibition at mima, Quietus: the vessel, death and the human body. I have been a long-time admirer of Julian’s beautiful urns and sarcophagi, and my poem ‘The Firing’ was based on his work (here it is, along with some other poems from the book Fetch, on Michelle McGrane’s Peony Moon site: http://peonymoon.wordpress.com/tag/tamar-yoseloffs-the-firing/).

It was a glorious day, and the sun beamed brightly into the education room, where we spent the afternoon reading poems and talking about that most taboo and difficult of subjects: death. We started with some thoughts on the title of the show, and the meaning of ‘quietus’, a word we’ve lost in modern grammar, but charged with multiple meanings: a release, a calming, and perhaps more accurately for Julian’s show, a place between life and death. The word comes from the Latin quietus est = ‘he is discharged’, as from a debt. In Shakespeare’s Sonnet 126, all the meanings of the word come together in the final line:

Sonnet 126

O thou, my lovely boy, who in thy power

Dost hold Time’s fickle glass, his sickle, hour;

Who hast by waning grown, and therein show'st

Thy lovers withering as thy sweet self grow'st;

If Nature, sovereign mistress over wrack,

As thou goest onwards, still will pluck thee back,

She keeps thee to this purpose, that her skill

May time disgrace and wretched minutes kill.

Yet fear her, O thou minion of her pleasure!

She may detain, but not still keep, her treasure:

Her audit, though delay’d, answer’d must be,

And her quietus is to render thee.

( )

( )

We pondered the ‘missing’ couplet. Is this a deliberate silence, to echo the silence of passing? The 12th line feels like an ending, a closure, but Shakespeare is too great a master of the sonnet not to be hinting as more by the absence of lines 13 and 14.

We moved from Shakespeare, to Sir Thomas Browne (readers of Invective will already know of my love for his essay ‘Urne-Buriall’) to Sylvia Plath’s haunting and strange ‘Edge’, the final poem she wrote before taking her life. In it, she talks about the dead woman as ‘perfected’, and compares her to a classical statue:

Edge

The woman is perfected.

Her dead

Body wears the smile of accomplishment,

The illusion of a Greek necessity

Flows in the scrolls of her toga,

Her bare

Feet seem to be saying:

We have come so far, it is over.

Each dead child coiled, a white serpent,

One at each little

Pitcher of milk, now empty.

She has folded

Them back into her body as petals

Of a rose close when the garden

Stiffens and odors bleed

From the sweet, deep throats of the night flower.

The moon has nothing to be sad about,

Staring from her hood of bone.

She is used to this sort of thing.

Her blacks crackle and drag.

Does the last line refer to the blackness of night, and by extension, the total blackness of death? Some critics think that ‘blacks’ could be mourning clothes, a stiff taffeta gown, as donned by a Victorian widow, another kind of costume the woman might wear (like the toga). Others think that ‘blacks’ are a reference to stage curtains, perhaps a pun on ‘it’s curtains for her’ but also evoking death as an act of theatre (which takes us back to ‘Lady Lazarus’ and the ‘peanut-crunching crowd’, the poet’s audience, her witnesses to the attempts she made on her life).

We read ‘Child Burial’ by Paula Meehan, a painful and terrible elegy about the loss of a child. And ‘Because I could not stop for death’ by Emily Dickinson, where death is a suitor, a kindly gentleman caller willing to pick you up in his carriage and take a you on leisurely drive out to the cemetery. And then we had a break for lunch and a walk around the galleries.

Although poems are normally two-dimensional objects, there is always the hand and heart of the poet behind them, and so I can’t help but picture the author, at his or her desk, in the act of writing the poem. I always think of Plath’s desperate last days during that cold London winter when I read ‘Edge’, and it makes the poem even more unbearable. There is something about Julian’s pieces that are at once personal and public, like poems. They often take on human forms – as Julian points out, the terms for the parts of pots are taken directly from the body:

The concept of anthropomorphism is central to the identity of pottery. We use bodily terms such as neck, shoulder, hip and foot to describe the constituent parts of a pot. And the very nature of the vessel as a container, a holder of things, is analogous to the idea of the body as a physical container for the soul or spirit.

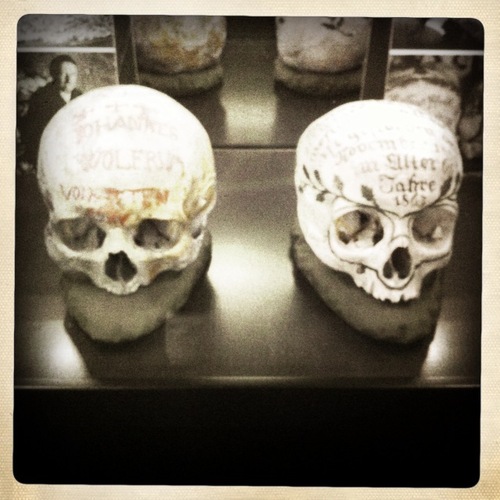

The Reliquary for a Common Man is a single jar of bone china. To say it contains the ashes of Julian’s uncle, Les Cox, does not describe it fully – some of his ash was used in the fabric of the jar itself. Perhaps the best way to think of this jar is as an ‘auto-icon’, a memorial that contains physical remains of the subject. Most reliquaries contain bones or other fragments of saints, so this is not a new idea, but somehow one which has become alien to us at the beginning of the 21st century. The room where the jar is displayed contains two screens, one showing home movies from the 50s and 60s, the other a series of still photographs which trace Les from childhood to old age. A recording of his voice plays into the darkened gallery. The effect should have been ghostly, but actually, I felt Les’s presence very strongly, his living presence – and I have never been susceptible to spiritualism or stories from beyond the grave. I was in the room with him, not only his image and his voice, but also some small physical fact of him, absorbed into the jar. Isn’t it true we become something else when we die – the shape and scale of us no longer exists. Maybe this is what Plath was striving for in ‘Edge’ – to take a different shape, to make herself into something else.

The other piece that especially moved me was the Columbarium – a word I’ve always loved, which comes from the Latin for ‘dove’, because the shape and compartments resembled a dovecote, but also makes me thing of the dove of peace, the holy spirit rising beyond the body. Julian’s Columbarium consists of 130 pots which create a tower, to suggest a community, the way we all come together democratically in death.

We came together again after lunch to share our poems, which were all extraordinary statements on the process of remembering and honouring. The whole experience was, surprisingly, joyful and life-affirming.

Julian’s show continues at mima until 11th November:

http://www.visitmima.com/exhibitions/currentdetail.php?id=98