The metaphor of ‘poem as room’ is a common one – indeed the word stanza comes from the Italian for ‘a room or standing place’. A poem is self-contained; you can think of its walls as the white area around it. It occupies a space – on a page, in a book, and the dimensions of its words contain a music that can be played with the voice, as well as meanings that connect the external experience of print with the internal experience of thought and feeling. A poem explores the interior world of human beings, and in turn we live inside interiors – between walls, hidden from others, in spaces we build to hoard our privacy. Homes are structures, just as poems are structures.

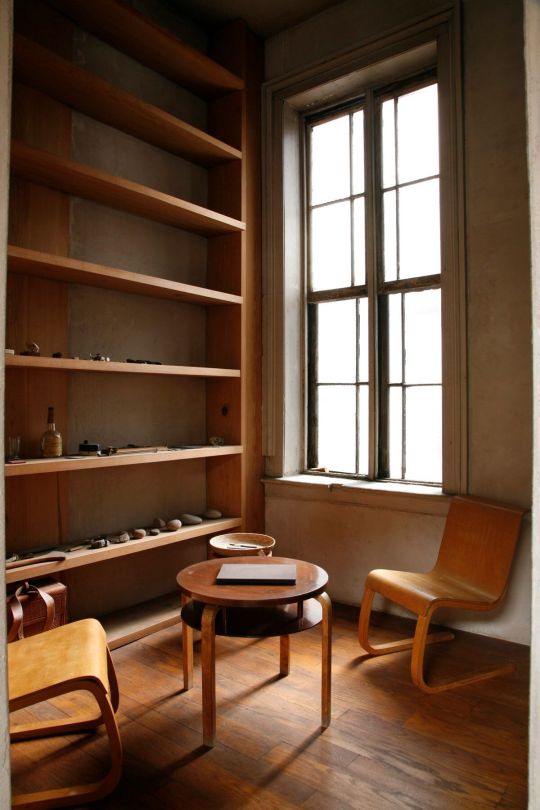

I was thinking of these connections again when visiting 101 Spring Street, which can’t simply be described as Donald Judd’s home and studio. 101 Spring Street was Judd’s first great experiment with structure. Walking through its vast open spaces now suggests these questions: how does someone live inside a building? And if that someone is an artist, how does he pay attention to what he places around him? How does that placement affect what he then makes?

In 1968 Judd purchased a five-story cast-iron building on the corner of Spring and Mercer in Soho. At the time, you could buy a whole warehouse around there for a song (Judd paid $68,000, money he’d acquired from an artists’ grant), as the surrounding streets were still pretty rough. But artists, always the front guard of urban renewal, could see the potential in those huge open spaces with enormous windows that let the light in.

In his 1989 essay 101 Spring Street, Judd outlines his ethos for the restoration of the building, which he found in a terrible state:

The given circumstances were very simple: the floors must be open; the right angle of windows on each floor must not be interrupted; and any changes must be compatible. My requirements were that the building be useful for living and working and more importantly, more definitely, be a space in which to install work of mine and of others.

(Here is a link on Places Journal to the essay in full: https://placesjournal.org/article/101-spring-street/)

What Judd created was building as sculptural installation. He took into account the proportions of the rooms, the height from floor to ceiling, and carefully considered where to place each object so that it might enter into a kind of dialogue with the building. That consideration moved from modest bowls and books, to tables and chairs (eventually, Judd would expand his practice into furniture making, perhaps as a way of exploring this issue) – to the intense light sculptures of his great friend Dan Flavin, and other art works, including a beautiful twisted wreck of car parts by John Chamberlain, and of course his own geometrical exercises in aluminium.

Judd and the artists of his generation were thinking about industry – how men forge in heat the shapes that contain us – right there in Soho, where the history of manufacturing began, and how to translate that into art. One reason Judd fell in love with 101 Spring was that it was made of cast iron, a material men have been using to make things since 5th century BC, when the Chinese produced cast iron pots.

I often think words have the look of something forged on the page. In letterpress printing (which involves hot metal press techniques), the words ‘bite’ into the paper, and you can see the mark of a word’s ‘teeth’ around it. Poetry in particular – as we’ve already said, the poem provides its own frame – the white field it occupies.

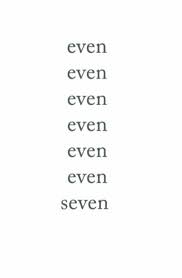

Here is a poem by Aram Saroyan, which I love for its simplicity, its basic mathematical pleasure, but also its architecture – its tribute to the classical perfection of columns. It plays with the known rules of grammar – if the ‘s’ added in the final line were at the end of the word, it would suggest plurality (but it would also tell a numerical lie, as seven is not an even number) but at the beginning, it simply tells us how many times the word ‘even’ has been repeated, while continuing the repetition. Saroyan was writing concrete poems (even the term nods to its architectural properties) like this one at the same time Judd was first pacing the floors at 101 Spring Street; Saroyan points to Judd as one of his influences. He said Judd’s work ‘balances the environment’; I love his balancing act with words. They are surprisingly solid.

In 1986, Judd wrote: A definition of art finally occurred to me. Art is everything at once. Insofar as it is less than that it is less art. In visual art the wholeness is visual. Aspects which are not visual are subtractions from the whole.

It seems to me that’s what happens with poems too. Saroyan’s structure is perhaps an extreme example, but if you try to remove one word (like in Jenga), you risk the whole thing toppling. I left 101 Spring Street thinking about form, and how important it is in making things, anything really – sculptures, buildings, pots, poems – and how difficult it is to achieve. And how Judd spent his whole life looking and experimenting, and retained the patience to keep trying.

With my thanks to the Judd Foundation for their permission to reprint the photographs of 101 Spring Street included in this post.

Charlie Rubin. 2nd floor, 101 Spring Street, New York, NY.

Joshua White. Exterior, 101 Spring Street, New York, NY.

Mauricio Alejo. Library, 3rd floor, 101 Spring Street, New York, NY.

All images © Judd Foundation / Artists Rights Society (ARS)