A month ago I posted in preparation for my Hayward course, The Point of the Poem, inspired by the Martin Creed exhibition What’s the point of it? Now I am posting at the end of the course, which seemed to pass very quickly – perhaps in the way that Creed’s work is often about something that can happen in an instant, a sudden revelation.

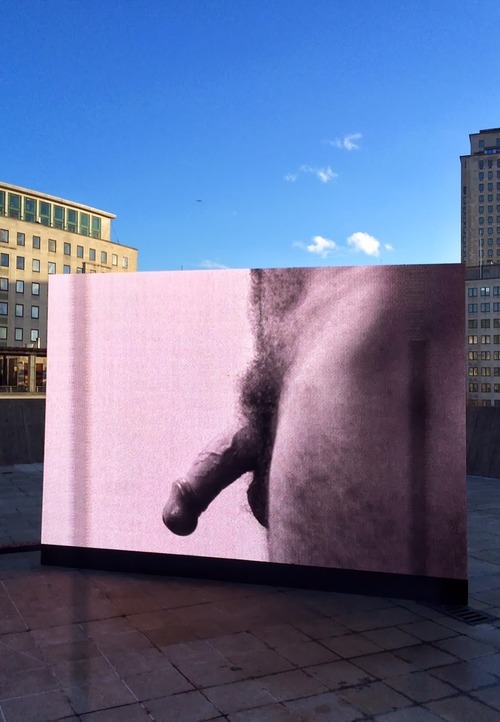

As predicted last month, we did go a little crazy, reciting Schwittersesque sound poems (even having a communal performance of laughter in the middle of the gallery), discussing Snowballs after experiencing the Balloon Room (or to give it its proper title, Half the Air in a Given Space), talking tempo after viewing a film of the rising and falling of a male organ (projected on an outdoor wall on a balcony of the Hayward – without doubt the strangest experience I have had in all my years of teaching). We ended the course on a good old fashioned debate about Creed’s work – its detractors labelling it puerile, tedious, shallow; its supporters calling it playful, humorous, celebratory.

And we did look at some fabulous poems along the way. From this sonnet by Edwin Morgan, a variation on a statement of John Cage’s (considering Creed’s use of repetition in his work):

Opening the Cage: 14 Variations on 14 Words

I have nothing to say and I am saying it and that is poetry – John Cage

I have to say poetry and is that nothing and am I saying it

I am and I have poetry to say and is that nothing saying it

I am nothing and I have poetry to say and that is saying it

I that am saying poetry have nothing and it is I and to say

And I say that I am to have poetry and saying it is nothing

I am poetry and nothing and saying it is to say that I have

To have nothing is poetry and I am saying that and I say it

Poetry is saying I have nothing and I am to say that and it

Saying nothing I am poetry and I have to say that and it is

It is and I am and I have poetry saying say that to nothing

It is saying poetry to nothing and I say I have and am that

Poetry is saying I have it and I am nothing and to say that

And that nothing is poetry I am saying and I have to say it

Saying poetry is nothing and to that I say I am and have it

To a dash of e.e. cummings (thinking about Creed’s obsession with counting:

one’s not half two

one’s not half two. It’s two are halves of one:

which halves reintegrating, shall occur

no death and any quantity; but than

all numerable mosts the actual more

minds ignorant of stern miraculous

this every truth-beware of heartless them

(given the scalpel, they dissect a kiss;

or, sold the reason, they undream a dream)

one is the song which fiends and angels sing:

all murdering lies by mortals told make two.

Let liars wilt, repaying life they’re loaned;

we (by a gift called dying born) must grow

deep in dark least ourselves remembering

love only rides his year.

All lose, whole find

To this riff on the letter ‘A’ by Christian Bök (examining the way Creed uses chance operations in the work – for example, his stripe paintings, the length of which are dictated by the length of the brushes in his pack)

from Chapter A

(for Hans Arp)

Awkward grammar appals a craftsman. A Dada bard

as daft as Tzara damns stagnant art and scrawls an

alpha (a slapdash arc and a backward zag) that mars

all stanzas and jams all ballads (what a scandal). A

madcap vandal crafts a small black ankh – a hand-

stamp that can stamp a wax pad and at last plant a

mark that sparks an ars magna (an abstract art that

charts a phrasal anagram). A pagan skald chants a dark

saga (a Mahabharata), as a papal cabal blackballs all

annals and tracts, all dramas and psalms: Kant and

Kafka, Marx and Marat. A law as harsh as a fatwa bans

all paragraphs that lack an A as a standard hallmark.

Mostly, I wanted to pick up on Creed’s love of experimenting, of having fun – entering the work from a place of indecision, indeterminacy, just waiting to see what would happen next. What happened for us was that a collection of surprising and extraordinary poems were generated. We have Creed’s crazy vision to thank.