Readers will know that I have been immersed in the fabulous Joseph Cornell show at the Royal Academy for the last month, as I have been running a course called Containing the World in Words. With Cornell’s dream boxes crowding my imagination, I took some time off to head to Venice for the Biennale (and the Redentore festival, which falls conveniently near my birthday). I discovered the city crammed with vitrines and glass cases of every description, marvelous wunderkammers stuffed with incredible objects. Cornell had travelled with me, and remains a guiding force for a new generation of artists concerned with collecting such things that represent their age, and preserving them for future generations.

Of course, Cornell is no stranger to

that city (or at least his works aren’t; he famously never travelled beyond New

York) as four of his magical boxes grace the mantelpieces in Peggy Guggenheim’s

palazzo. His fortune-telling parrot winks from its perch, and a ghostly palace

twinkles in mirrored gloom.

And over in another magical palace, the Tre Oci (the neo-gothic fantasy conceived by the artist Mario de Maria), Mark Dion presents several installations around the idea of taxonomy. Included is one of his ‘cases’, filled with finds dredged from the canals and lagoon of Venice. It resembles the heavy furnishings of the old-fashioned museum; Dion is of my generation, so will recall being dragged to such places as a child, institutions lined with great expanses of dark wood display cases, most of their treasures behind doors and panels and inside drawers. What I love about Dion’s cases is that they are thrown open, and so their contents are immediately visible – the museum exploded. The stuff of the canal, just broken bits and bobs, is presented as a rare find (just as Cornell made his dime-store materials into precious and coveted objects).

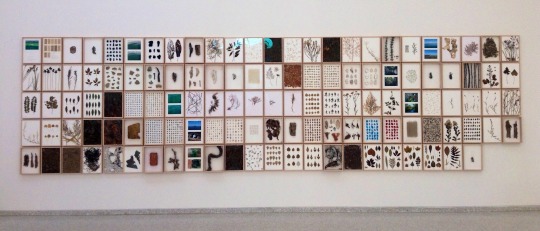

Another element to Dion’s work is one of ecological preservation. In this he is akin to herman de vries (who insists on spelling his name in lower-case letters ‘to avoid hierarchy’), the artist chosen to represent the Netherlands this year. Like Dion, de vries collected objects from the lagoon and the city for his Biennale installations. His background as a horticulturalist is evident in the series of framed plants and flowers, like those you might find pressed in a book as keepsakes. Unfortunately we were unable to get to the second part of his show, held on the deserted island of Lazzaretto Vecchio, which housed a plague hospital in the sixteenth century; there are known to be at least 1500 skeletons of plague victims buried on the island. This must have been a very poignant experience, as de vries work for me is concerned about the human mark on the land.

The human mark on the land is most

evident in Fiona Hall’s stunning installation for the Australian pavilion. Hall

plunges us into darkness, her museum cases dramatically spot lit, like the

theatrical presentation of the Renaissance Wunderkammers. But like de vries’s

meditation on death, present under the feet of those who make it out to

Lazzaretto Vecchio, Hall is telling us that humans may soon only exist as a

museum exhibition. Lining the walls around her elaborate displays are a number

of clocks, faces painted over with skulls, scythes, and other symbols of death.

Their ticking and chiming becomes an eerie reminder of our brief time on earth.

In the cases are the objects of human endeavor, such as atlases, but also

headlines that scream the truth of global warming, the destruction of the

natural environment. Standing in the centre of an octagon of cases, we too

become part of the ghastly installation. We too are museum pieces.

Which takes me back to Cornell, who, in his temporary residence in London, has reminded me to find wonderment in even the smallest tokens. So much of his work is also about time, and how, if we not careful to preserve the past, the great achievements we might have made will inevitably be lost.