On the occasion of Linda Karshan’s retrospective at the Redfern, I wanted to post an essay I wrote about our collaborative project, Marks, which was published as a limited edition artist’s book by Pratt Contemporary Editions in 2007. Linda’s show features work from 1992 to 2010 and is on until 16th October.

http://www.prattcontemporaryart.co.uk/Linda%20Karshan/Karshan%20LOPF1.html

http://www.redfern-gallery.com/pages/artistinfo/16.html

23rd February 2005

A threat of snow. The sky’s light grey, strangely empty. Linda and I meet in the Oval late morning, each in our serious heavy-duty coats, go for a coffee near the station. We talk about real North American winters, the sort of cold that enters your bones, real snow. Not like here, where everything grinds to a halt with the first flakes. We talk about how artists and writers come together, sometimes easily, sometimes with difficulty, and decide we don’t want to plan anything. Nothing should be forced.

We drive south; through Brixton, Camberwell, Dulwich. The landscape changes from urban tower blocks and concrete, to 30s houses that dream of suburbs; that terrain which is so familiar to us of well-cared-for lawns and doormats that say welcome. Linda has mentioned before that she can identify with the childhood in my poems. America is about childhood for both of us now, since we have lived our whole adult lives somewhere else. I think of a quote from Nathaniel Hawthorne:

The years, after all, have a kind of emptiness when we spend too many of them on a foreign shore. We defer the reality of life, in such cases, until a future moment when we shall again breathe our native air; but, by and by there are no future moments; or, if we do return, we find that the native air has lost its invigorating quality, and that life has shifted its reality to the spot where we have deemed ourselves only temporary residents. Thus, between two countries we have none at all, or only that little space of either in which we finally lay down our discontented bones.

My mother used to carry that quote inside her wallet, the paper brown and brittle, and so I knew it from very early on, before I had any inkling that one day I would be an expatriate, as Hawthorne was, as Linda is. I always wondered what it meant for my mother, who is 76 and has always lived in America. Could she somehow sense my future in it? She must have cut it out of an article published in ArtNews Annual in 1966, where it was in turn quoted by John Ashbery, writing on American painters in Paris. Later, driving home, Linda will tell me about her year at the Sorbonne, the excitement of Paris in the 60s, the time of the painters in Ashbery’s article, and how she knew it was the place for her, and I will remember that same feeling of arrival in the late eighties, when I first moved to London.

But that’s later. We park on a tree-lined residential street, Sunray Avenue (like Cornell’s Utopia Parkway) and I can’t guess where Linda is taking me. I follow her up the driveway of a family house with a bright pink corrugated metal garage door. It tilts open to reveal chairs, a mirror, a bicycle, a filing cabinet, stacks of boxes. It is a surprise, but later it makes sense to me, that you should have to pass through that space of memory and nostalgia, the contents of a family’s life, to get to Linda’s studio.

She takes me through another door, and we are in a small white corridor between the house and the back garden. We open another door and head up the garden path. Through the window, I can see into the kitchen of the house. Cluttered, with a big pine table. A woman is seated at the table, drinking her coffee, watching us. We walk past a trampoline, a child’s model fairy castle. There is snow lying on the tree branches, a light frost on the grass. At the end of the garden is a plain wooden building, with a small porch, like a Scandinavian hut. It looks at if it has travelled through the sky, landed here.

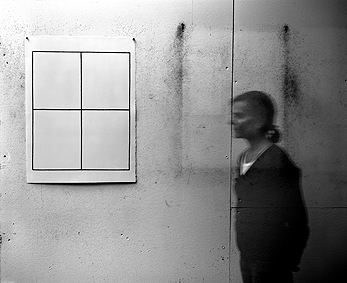

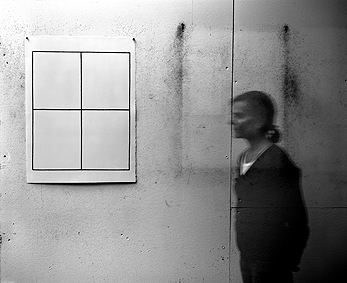

Linda opens the last door, Alice negotiating Wonderland, and we are in the studio. It’s like one of those spartan New England churches. Linda had mentioned the spiders, and how when she had arrived in the studio Monday morning, she found their webs matched one of her grids. And here are the webs, cross stitched into the beams. Linda had been wondering what she wanted me to see when I first walked in, and when she arrived in the studio Monday morning, she found what she wanted to show me was already there. And here are the pictures, the clean white of the paper against the studio wall, a halo of pinpricks around them, from other pictures that have occupied this space.

But I won’t talk about the pictures. What I write will talk about the pictures.

Linda pulls out other drawings from thick stacks in the corner, explains how one led to the next, which led to the next. Everything is chance. I tell her I’m reading Molloy. She has mentioned his sucking stones in her writing, and I’ve been trying to make sense of the reference. I get it now—the comfort of doing something you understand, you’ve done often. Something primitive, almost childlike. I pick up my copy, read her the line:

If you think of the forms and light of other days, it is without regret.

I already have an idea that this will be my beginning, as I look at the bright grey light that fills the studio. Everything is chance.

We spend the morning talking, looking at drawings, books. Feeling our way in. Thinking about progression. We drive to the Dulwich Picture Gallery to have lunch. There is snow on the lawn. We talk about Soane and how his buildings look like mausolea. Solid, irrefutable. Soane wanted to control space, the relationships of things inside a room. What Linda does is like the blueprint, a way of reading space. A map of the interior.

We go back to the studio, with Soane’s symmetry in our heads, read Donne’s ‘A Valediction forbidding mourning’ which ends with the line:

Thy firmnes makes my circle just,

And makes me end, where I begunne.

Then Linda starts to draw, and I watch her make the line down the centre of the paper, in her rubber gloves, like a surgeon halving the body with a scalpel. The precision of it. I know that this image will go into the poem, that moment of beginning, of entry. Here’s my beginning… Linda talks as she draws, she counts silently, she taps her foot. She tosses a drawing to the floor, it floats like a sail. She crosses the room, leaves her footprint on the paper as she passes. She takes up another paper, the same motions, the lines traced and retraced, she turns it over, finds the ghost of the drawing beneath, begins to trace the lines again. As I watch her, I am writing, just randomly, things I’m thinking, things she’s saying. The writing is coming out in short lines, almost following the motion of Linda’s hand. This feels right to me.

Before we go, Linda shows me a folder of work done by children who visited her Soane exhibition. They were asked to describe her drawings. One of them wrote:

There were spaces. They were made out of space.

We drive back north, through London in rush hour, but I am thinking of space, how difficult it is to leave the studio, return to the world of things. Linda makes this journey every day, from her home to the studio and back. A to B to A. The way we navigate our places, the way we move through space.

Something else one of the children wrote about Linda’s drawings:

The whole earth is like that.

Yes, it is.