Rodin said:

There are unknown forces in nature; when we give ourselves wholly to her, without reserve, she lends them to us; she shows us these forms, which our watching eyes do not see, which our intelligence does not understand or suspect.

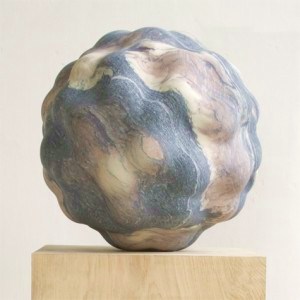

Peter Randall-Page's work feels ‘unmade’; strange organic shapes mimicking pods and seeds. The pieces on display at the Jerwood Space are sculpted from rare Rossa Luna marble, which is cool and smooth, multi-hued, from pale beige to bruised purple. Like dark planets.

Down the road on Hopton Street, behind the gates of the 18th century almshouses, two pocked, charcoal-dark forms frame the path; as if they have landed there from nowhere, as if they have been there forever. We saw them in twilight, which lended them added mystery. The wall pieces next door at Purdy Hicks resemble Indian vegetable prints or recent aboriginal art. The rust-red clays reminded me that autumn is truly upon us.

http://www.jerwoodgallery.org/news/jerwood-news/peter-randallpage-jerwood-space