Another poem from my Pollock sequence. Pollock wanted James Dean to play him in the movie of his life, which would be like getting James Franco (brilliant as Ginsberg but far too beautiful) to play him now instead of Ed Harris, who was tough, edgy, tortured (and not too beautiful), and who had enough of Pollock’s physical attributes to pass for the real thing. Pollock was attractive to women, but he was a bruiser, with a heavy, hangdog face. He looked like his paintings look: difficult, untidy, unpredictable.

But you can see why when Pollock looked in the mirror, he saw Dean. His ego (and a reasonable amount of drink) allowed him to envision himself as a film star, an idol, and the press agreed. When Life magazine ran a photo feature with the headline, Is This the Greatest Living Artist in the United States?, Pollock knew the answer was YES. It was 1949, long before Basquiat and Tracey Emin were even born, but it was Pollock who gave them the model for artist as temperamental star; so that the art and the personality become intertwined in people’s minds (and sometimes the personality becomes a greater force).

But there was an inner Dean in Pollock too: the biker-jacket-and-Marlboro aesthetic, the tormented genius. Pollock recognised Dean as a kindred spirit. He also recognised someone who knew how to “manage” his image. And they crossed into each other’s worlds; Dean wrote poetry, Pollock was the star of Hans Namuth’s films where painting becomes an action sequence (like a fight or a car chase).

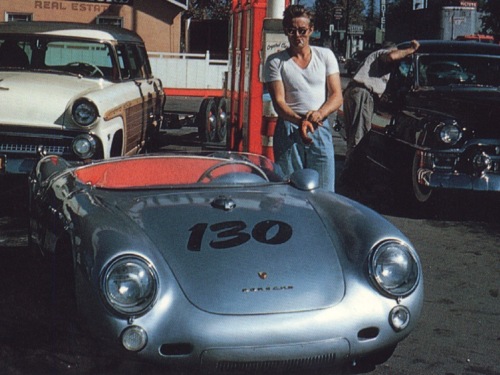

They were both killed in car accidents, within a year of each other. Dean died on 30th September 1955 at the age of 24. His Porsche 550 Spyder, known as “Little Bastard” was completely destroyed in a head-on collision. Rebel Without a Cause was released posthumously. In that film, Dean’s character, Jim Stark, is challenged to a “chicken run”, a drag race towards a cliff edge in stolen cars. Pollock was a fan of the movie. It is commonly accepted that his “accident” was probably not an accident. On his way back from a party on 11th August 1956, he drove his Oldsmobile convertible into a tree. He had been drinking. He was 44. One of his passengers, Edith Metzger, was also killed, but his lover, Ruth Kligman, survived (earning her the nickname “Death Car Girl”).

So here’s the poem. The passages in italics are lines from Rebel Without a Cause.

Rebel without a Cause

Lights. Camera. Action. Paint

whirls off the brush, as he drips

and dives:

GREATEST LIVING ARTIST IN AMERICA

Posing with his new Oldsmobile,

itching to take her out

for a spin, take in a matinee.

At the Regal lights dim

on the plush red, Jimmy’s face

reels on the screen:

Once you been up there

you know you’ve been someplace.

The boy in Warnercolor, the boy

in the newsreel. Wheels

spun out, Porsche scrapped.

Like the magic trick, sawn in half.

The artist slumps in the row at the back.

He’s seen this flick before:

I don’t know what to do anymore.

Except maybe die.

Good trick:

exit stage right

before you crash and burn,

because tomorrow you’ll be nothing.

Better to be a dead hero

than a deadbeat. Plush red,

lights dim.

You can wake up now,

the universe has ended.