In Italo Calvino’s book Invisible Cities, the explorer Marco Polo returns from his voyages to regale Kublai Khan with stories of the many and varied places he visited in his travels. But as his narratives progress, the ruler begins to question the reliability of his young adventurer. It becomes clear that the numerous cities Polo claims to have visited are merely different facets of one city – Venice, Polo’s home town. What to make of these ‘imagined’ cities once the truth is known? The book becomes not a travelogue, but a work of psychogeography, an imagining of many possible experiences within one urban centre, where buildings, people and ritual come together:

The city, however, does not tell its past, but contains it like the lines of a hand, written in the corners of the streets, the gratings of the windows, the banisters of the steps, the antennae of the lightning rods, the poles of the flags, every segment marked in turn with scratches, indentations, scrolls …

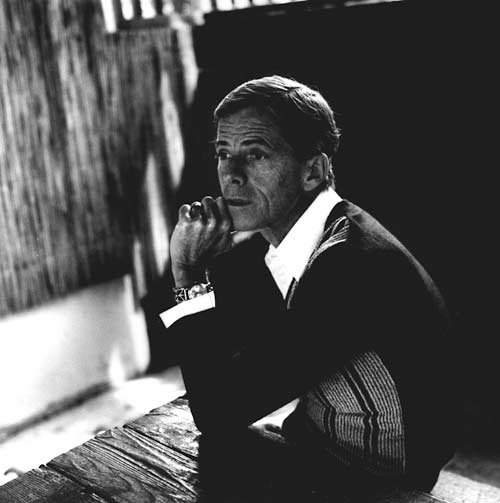

I remembered Calvino when visiting Julie Mehretu’s current exhibition at White Cube, Bermondsey. It was not my first encounter with Mehretu’s work, having seen her paintings first in Venice (making the connection to Calvino more overt), then in Kassel. Two very different urban experiences: I have written about both cities here on Invective, and it strikes me now that both Venice and Kassel are appropriate sites for Mehretu’s project. Venice represents the meeting of east and west, a strange confection of ornate palazzi but also brooding corners and dark dead-ends. Kassel is a palimpsest – a city that will never shake its complete destruction, even through its reconstruction.

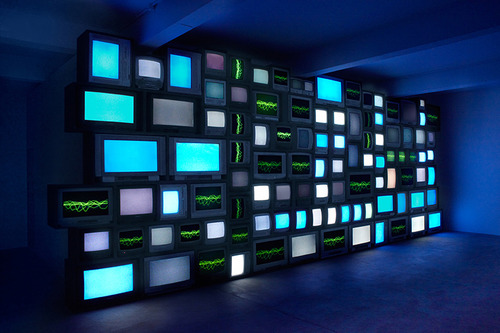

Mehretu’s cityscapes, like Calvino’s, are unreliable. You cannot move freely through the streets or chart a route between two places. Through a layering of architectural drawings – showing features such as columns and porticos – and city planning documents, Mehretu builds a place of frenetic energy and multiple diversions. Over these layered architectural elements, she creates a series of smudges and lines – almost destroying her creations, in the same way the wrecking ball levels buildings everyday (slow to erect, fast to collapse) – and over that, she paints coloured acrylic flourishes, long arcs and stripes, like graffiti (the unofficial street art that she cites as one of her influences). She says of these ‘marks’:

I think of my abstract mark-making as a type of sign lexicon, signifier, or language for characters that hold identity and have social agency. The characters in my maps plotted, journeyed, evolved, and built civilizations. I charted, analyzed, and mapped their experience and development: their cities, their suburbs, their conflicts, and their wars. The paintings occurred in an intangible no-place: a blank terrain, an abstracted map space. As I continued to work I needed a context for the marks, the characters. By combining many types of architectural plans and drawings I tried to create a metaphoric, tectonic view of structural history. I wanted to bring my drawing into time and place.

She calls the finished canvases ‘story maps of no location’, every city and no city at once. The idea of stories, of narratives, of characters, brings us back to psychogeography, which is concerned with the emotional responses of the individual to a city. Recently in this blog I mentioned Rebecca Solnit’s alternative mapping of her home town, San Francisco, and her definition of places as ‘stable locations with unstable converging forces.’ Mehretu’s approach is similar; she says:

I am interested in the potential of ‘psychogeographies’, which suggest that within an invisible and invented space, the individual can tap a resource of self-determination and resistance.

Her recent ‘Mogamma’ paintings contain overlaid images taken from 31 different squares which became centres for revolt and conflict during the Arab Spring. These are ‘charged places’ for Mehretu, and even post-revolution, they hold the turmoil of their association to these events in their very bricks. Mehretu herself fled a place of conflict – Addis Ababa during the Ethio-Somali war – when she was seven years old. In her work, she is placing herself back in the centre of conflict, asking the question: ‘how do I look at myself in this moment? How do I exist in a larger social and historical moment?’ The crisis, as a human being, globally, environmentally, politically, is always to consider how much power the artists’ mark has in our time.

I’ll end with a poem by Weldon Kees which seems to chime with Mehretu’s project:

To Build a Quiet City in His Mind

To build a quiet city in his mind:

A single overwhelming wish; to build,

Not hastily, for there is so much wind,

So many eager smilers to be killed,

Obstructions one might overlook in haste:

The ruined structures cluttering the past,

A little at a time and slow is best,

Crawling as though through endless corridors,

Remembering always there are many doors

That open to admit the captured guest

Once only.

Yet in spite of loss and guilt

And hurricanes of time, it might be built:

A refuge, permanent, with trees that shade

When all the other cities die and fade.