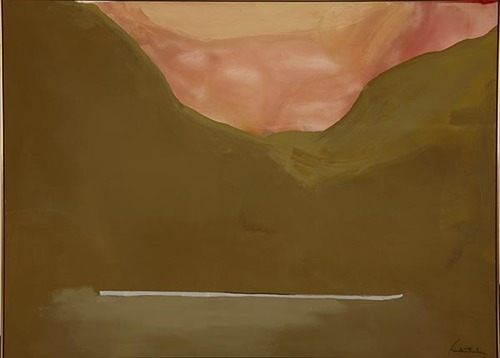

Helen Frankenthaler wrote of her 1972 painting, ‘Burnt Norton’:

I was thinking about Eliot, making order out of chaos, of light and dark. Like Eliot’s poem, the painting’s simplicity is arrived at after a great deal of complexity. My work is never playful. This seemed at the time an especially serious and weighty picture to solve.

The resulting work seems to be a distillation of what she found in Eliot’s poem, deceptively simple in its reduction, until you learn that Frankenthaler worked on the grey-blue horizontal line that interrupts the brown near the lower edge of the picture for many weeks until she got it right. Is that line the ‘still point of the turning world’ that Eliot envisioned, something not fixed, but not static? The line hovers in Frankenthaler’s painting, ‘a white light still and moving’; it could be a body of water, a break in the relentless brown of the hulking shape that dominates the canvas – a dark mountain range. There is a dip, a view through to a lighter horizon tinged with rose (the exact colour of ‘dust on a bowl of rose leaves’), something seen but not quite reached.

Eliot’s poem is about time, how from the present moment stretches both past and future. In Frankenthaler’s painting, it is tempting to see that line she struggled with for so long as the present, the dark mountain as the past, the rosy glow in the distance as the future. But that is perhaps too simple – a way of desiring meaning from a painter whose vision is never absolute. In that respect, Eliot is Frankenthaler’s perfect poet, dense and difficult in his subjects, but light and lyrical in his words.

Walking around the current Making Painting show at Turner Contemporary, I was struck again by what a brave painter Frankenthaler was, how she took all those butch abstract expressionist movements and softened them. But that makes her sound uncertain, and her canvases are big, bold, exploring colour and light the way Matisse did, but with the lyrical focus of Monet (I found the show’s attempt at a comparison with Turner distracting – he’s not the first painter I would think of as an influence on Frankenthaler, although when you look at their approach to similar subjects, of course there are some similarities). A film of her working shows her kneeling over a huge canvas placed on the floor – the technique of Pollock’s which freed her. But unlike Pollock, all bravado and splash, her gestures are slow, deliberate. And yet she is not as famous as he is, although she deserves to be. You look at Frankenthaler’s work and see the whole scope of Color Field painting opening up with those first grand gestures.

Frank O’Hara knew it. Eliot, for all his classicism, would not be the right poet to repay the compliment. O’Hara wrote of Frankenthaler’s work:

she is the medium of her material, never polishing her insights into a rhetorical statement, but rather letting the truth stand forth plainly and of itself.

But Eliot was more in my mind than O’Hara as I came out onto the front in Margate, thinking again of his efforts to connect nothing with nothing, and how Frankenthaler somehow nails it.