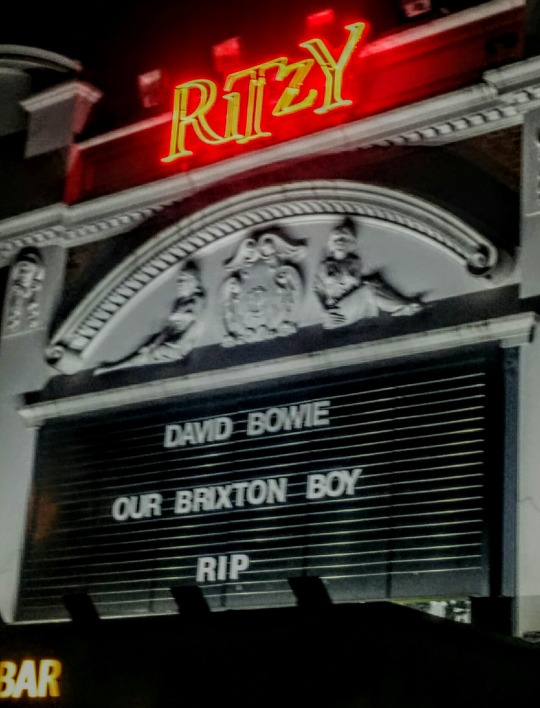

On Monday night, I stood in a crowd outside the Ritzy Cinema in Brixton.

The marquee above us read:

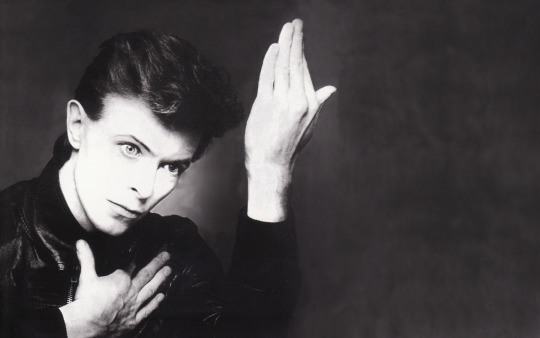

It seemed inconceivable that Bowie was really gone, although he’d always been like an alien who’d just dropped in for a while to see what was happening on earth before tripping off to other galaxies (I am thinking especially of his role as Thomas Jerome Newton in The Man Who Fell to Earth, a part that Bowie didn’t play as much as inhabit). He appeared to be immortal, perhaps because of his many reincarnations, from Ziggy Stardust, to Aladdin Sane, to the Thin White Duke. No one expected that he might actually die one day, and even on Monday morning, when the news was first announced quietly on his official Twitter site, no one believed it; people were still claiming it was a hoax until Bowie’s son, Duncan Jones, confirmed it, posting a photograph of Bowie as a young dad, hoisting little Zowie / Duncan on his shoulders. Since then social media has been overloaded with Bowie tributes and photos … but it still doesn’t seem real, just as he didn’t seem real.

For me the damascene moment was quite late, 1979 to be exact. Perhaps because suburban New Jersey was a backwater compared to sexy London, and American radio was blaring good old fashioned guitar rock like the Eagles and ZZ Top. I was navigating the first wave of British pop, always at least ten years out of date, first through the Beatles, then through the Yardbirds, Cream, the Zombies, the Moody Blues, early Pink Floyd. I was of course aware of Bowie. ‘Fame’ had been a big hit in the American charts. But it was his arrival on Saturday Night Live on December 15th 1979, when he played ‘Boys Keep Swinging’ with Klaus Nomi and Joey Arias as backing singers, all of them wearing tight pencil skirts, which coincided for me with the swirling epicenter of puberty. I was fourteen at the time, and very aware of boys, but not ones in skirts, and Bowie was the most beautiful man I’d ever seen. It was confusing, but also exciting, and that performance opened up the possibility that there were men who didn’t wear flannel shirts and swig Bud out of the bottle (and that they were probably all in London). I was a particularly awkward and gangly fourteen-year-old, still trying to overcome the tyranny of braces and glasses, and it would be a few more years until I embraced glitter eyeshadow and vintage tuxedo jackets, but seeing Bowie that night was a revelation. I felt like a misfit growing up in New Jersey – never accepted by the horsey set or the cheerleaders – but for the first time I could see how you might be proud of your difference, how you could construct a character out of your strangeness.

I covered the walls of my room in Bowie posters. He was a different man

in each one, a chameleon lover. I bought all his albums. I still have them in a

box somewhere, although I don’t have a turntable to play them on (I have him on

iTunes now). I know they would scratch and skip, because I played them to

death. He was the soundtrack to my later teenage years, and because of him I

started to be who I am now. ‘Heroes’ was my anthem, my ultimate desert island

disc, and it still is – the greatest cold war love song of all time.

In Brixton on Monday we stood in vigil. A guy in turned up in Windrush Square with a sound system in the back of his van, and we danced in the street. People had painted Aladdin Sane lightening bolts across their faces. Even the police were dancing. It was spontaneous, happy. But it still doesn’t seem real, and I am waiting for him to pop up any minute and tell us it was all a joke. But I’m listening to Blackstar as I’m writing this, and he’s singing Something happened on the day he died / Spirit rose a metre and stepped aside and it’s clearly his way of saying farewell. For me, the star will always remain lit.