Readers may recall I blogged about a fascinating walk I did last year, in the company of the poet Stephen Watts, exploring hidden corners of the East End that appear in WG Sebald’s novel Austerlitz. Keen to revisit some of those locations, my Hercules co-publisher Vici MacDonald and I took a small group of generous sponsors of Heart Archives (including author Sue Rose) on a short perambulation around the old Jewish cemeteries of Mile End. We were fortunate in meeting up with Susie Clapham, architect and chronicler of lost street furniture http://anomaliesofloststreetfurniture.blogspot.co.uk/. She has taken a special interest in the cemeteries, especially the one at Bancroft Road. More on that later.

We began in Alderney Road, where Stephen also began with his group some months back. As I mentioned in my previous post, Alderney Road is the location of the oldest Ashkenazi cemetery in the UK. Although Sebald chose to situate his protagonist in a house adjacent to the burial ground, he is unable to see into over the high wall. This seems to me to be a typical Sebaldean device – to give us a glimpse, a speck of knowledge, so that the quest becomes as crucial as the discovery. But just as Austerlitz is one day lucky enough to come across the open door in the wall, we too were given access.

It is, as I’ve said before, a beautiful and moving place, as Austerlitz says, ‘a fairy tale which, like life itself, had grown older with the passing of time.’ It may have meant more seeing as a fair proportion our little group, including Sue and myself, have Ashkenazi roots. Standing there I was reminded of a line from one of Sue’s poems, ‘Mahler 9’, in which she writes: ‘we all carry our dead / with us on a quest for new homes, the klezmer dance / in our head propelling us forward, the fiddle pulling us back.’

Susie took us round the corner into the Bancroft Road cemetery, which I had previously only seen from the street (many only glimpse it momentarily from the train, as they arrive into London via Liverpool Street), and what struck me most was how vulnerable that small plot feels amid the council blocks and early Victorian terraces of Stepney. The apple tree stranded at the far end by the fence, its fruit rotten and spoiled on the ground, seemed a metaphor for what has happened to the place, bombed in the war, vandalised in later years. There were a few stones still standing, some still legible. We were moved by the grave of a child, his stone although toppled, intact.

That ‘quest for new homes’ is something too that struck a chord with our group, assembled as we were from America, Canada and the Czech Republic. We found ourselves next on the Queen Mary campus, surrounded by bleary-eyed weekend students, viewing the Velho Novo Cemetery, a desert of the dead amidst the stark brick architecture of the modern university. I have written about the history of the Sephardi cemeteries when I visited with Stephen, but it is worth mentioning how strange these sites are in their modern context, especially the one bang in the middle of campus.

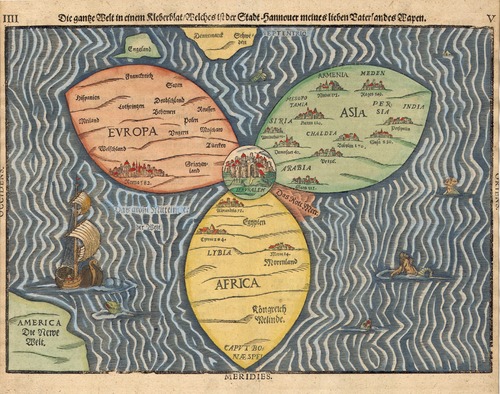

But it was the Velho Old which was most hidden, most secret of them all. A security guard escorted us through back alleys of the campus to a gate on the side of one of the dormitories, then through a courtyard enclosed in a metal fence, before finally opening a gate at the end. There is a fascinating history of the Velho Old site here: http://www.findagrave.com/cgi-bin/fg.cgi?page=cr&CRid=2246135. It is the oldest Jewish cemetery in the UK, the land gifted to the Sephardic community by Oliver Cromwell. It must be one of the most peaceful locations in London, but also one of the most alien. The traces of Hebrew and Portuguese (most of the inscriptions have been rubbed clean by age and pollution), the foreignness of the names we could still make out – all seemed to belong not only to another age, but another land altogether.

Possibly the oddest moment of our tour was when a local resident on the other side of the fence (ironically, an American) started speaking to us, shocked to find anyone in the cemetery (‘no one is ever in here’, he said). ‘Don’t worry, we’re not ghosts’ one of our party replied. But actually, it felt as if we were, as I always feel when visiting a cemetery, that strange exhilaration of being alive, with the dead under my feet, and thinking of the famous epitaph as I am now so you shall be.

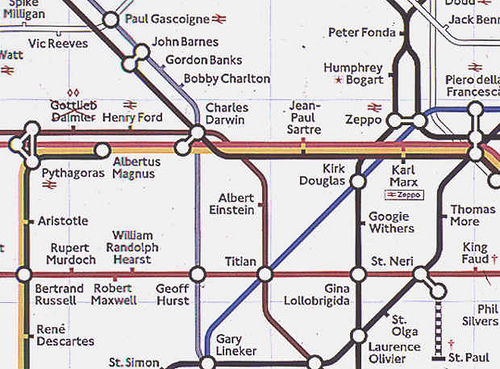

Formerly is an attempt to erect some unofficial blue plaques. The exhibition is looking lovely in its spot high over the Thames in the Poetry Library. From next week, we will be inviting visitors to create their own psychogeographical texts, based on their own wanderings, their personal maps. Watch this space.

Formerly is an attempt to erect some unofficial blue plaques. The exhibition is looking lovely in its spot high over the Thames in the Poetry Library. From next week, we will be inviting visitors to create their own psychogeographical texts, based on their own wanderings, their personal maps. Watch this space.