Readers of this blog will know that I have written about the artist Berlinde de Bruyckere after discovering her at the Venice Biennale last year. Her vast piece, Cripplewood, had a profound effect – its twisted and injured limbs were crammed into the claustrophobic, church-dark space of the Belgian pavilion. As I wrote at the time, de Bruyckere began the piece after encountering a massive tree that had been uprooted by a storm and had fallen in the middle of a road. From this she imagined a ruined cathedral, its roof vault collapsed in on itself.

The current show at SMAK in Ghent includes this piece. Inside a light, large gallery, it has a very different impact. Still powerful, but this time the tree is visible to us, and we can see the trauma of its bloodied surface, its construction (wax, formed to resemble wood). It becomes more of a vast supine monster than felled tree, reaching its strange tentacles into the far corners of the gallery. Exposed to us in the harsh white, we see trauma made plain; stretches of grey laced with red.

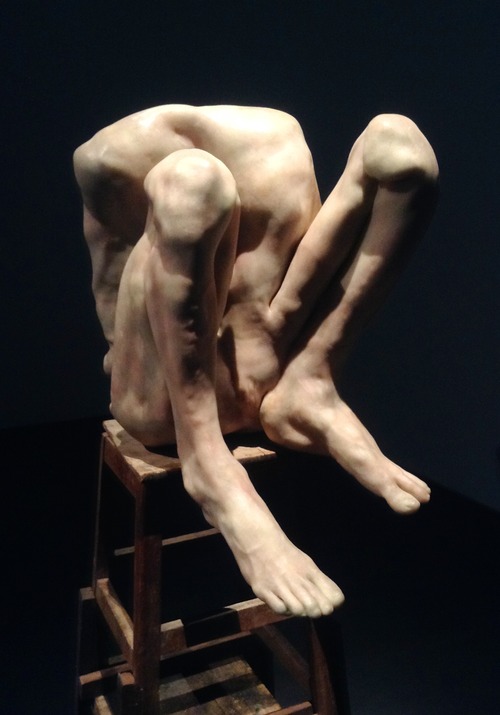

Trauma is the word I carry with me through the rest of the show. Here is the body bent over itself, as if trying to protect its delicate case, or the body jerked into an unnatural pose, pain coursing through every sinew. The pose is often one we recognise: de Bruyckere grew up in the city that gave us Van Eyke’s altarpiece, the centre of Netherlandish religious art, less beautiful and golden-hued than the Italian painters, more earthy and earthly; Christ resembles any ordinary man, he bleeds, we read pain in his face.

The other great influence is butchery. The artist’s father was a butcher and a recreational hunter, and she retains a childhood memory of animal carcasses strung up, exposing their inner workings. Into her monochrome palette one colour comes streaming: red. It’s the red of fresh blood, bright and horrible.

It is difficult to forget that this is the centenary of WWI, and scattered around the Belgian countryside are the grand cemeteries of that war. In de Bruyckere I’m also reminded of the sketches of the official war artist Henry Tonks, that displayed the most gruesome injuries (Tonks had trained as a doctor before he became an artist) but still managed to capture the humanity of his subjects, in their eyes, their composure. Having said that, the faces of de Bruyckere’s subjects are obscured; it’s the body that speaks.

It seems a strange thing to say, but the work is also beautiful. There is a delicacy and grace, especially in the drawings, where the pencil passes over the paper like a whisper.

This is a stunning and harrowing show. Having recently blogged about the Schiele exhibition, and the Nakeds at the Drawing Room (and having recently run a writing workshop for the Tracey Emin show at White Cube) it feels as if this is the culmination of thinking about the body and how it is exposed. I will be thinking about this work for a long time to come.