I’ve been trying to work out what it is I love about Antwerp. On one level, it’s like a fantasy, with its dark Medieval spires, cobbled streets and Netherlandish gargoyles crouching in the doorways of patrician stone buildings. There is something about scale as well; I know I’ve written here before of the charm of smaller cities, ones where the centre fits onto a single map and you feel you might be able to get the measure of the place in a few days.

It’s also very beautiful. We first meet the eponymous hero of Sebald’s Austerlitz as he is sketching the waiting room in the grand Centraal Station, and what follows is an amazing history of its construction:

when Belgium, a little patch of yellowish grey barely visible on the map of the world, spread its sphere of influence to the African continent with its colonial enterprises, when deals of huge proportions were done on the capital markets and raw-materials exchanges of Brussels, and the citizens of Belgium, full of boundless optimism, believed that their country, which had been subject so long to foreign rule and was divided and disunited in itself, was about to become a great new economic power.

It’s where the novel begins, in that incredible vast bourgeois station, which lends drama and opulence to arrival. Something of that sense of spreading across continents remains too as you exit the station: the citizens of the dissolved empire are all around. The station is next door to the zoo – I can’t think of another major city where you would find such a juxtaposition, which strikes me somehow as very Belgian, or at least Flemish – the more I travel around Flanders, the more I get the Belgian sense of humour, which is a bit rude, a little surreal. I love the sound of Flemish, its guttural drama. So much less refined than French; a dirty joke would certainly sound better in Flemish (maybe that accounts for their bawdiness). Part of the beauty of Flemish for me is not understanding a word of it, allowing the sound to float over me like some discordant piece of music.

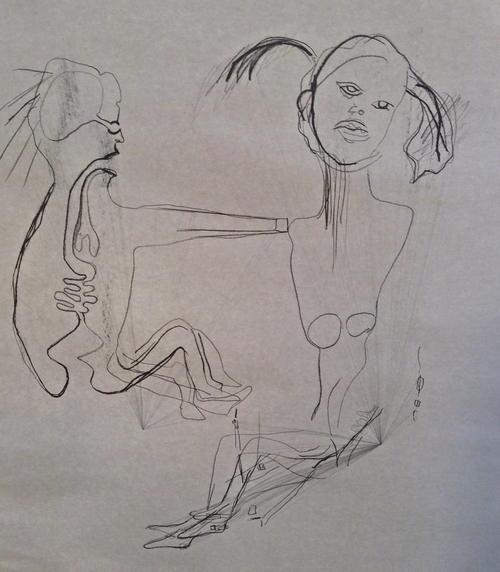

And so to Zeno X, and the new Mark Manders show. I discovered Manders’ work when he was representing the Netherlands at the 2013 Venice Biennale (he is Dutch, but has been based in Ghent for many years) and posted my impressions here at the time. Going to his show first, almost straight off the train, grounded me for the rest of the weekend. Manders’ project is about how we define ourselves in relation to our surroundings, so that many of the works are variations on the theme of self-portrait (the next day, I found myself thinking of Manders while staring at Van Eyke’s depictions of the great and the good of his day).

It’s an important consideration in a place like Belgium, where people move in and out of different languages – the most obvious shift being from Flemish to French. His work always seems to be in the process of being made, so nothing is ever quite finished, even once it appears within the pristine walls of the gallery. His piece, Landscape with Fake Dictionary, suggests this dilemma of navigating a city where many different languages are being spoken, but you can’t understand any of them. It put me in mind of the ‘fake newspapers’ he created for his Biennale show – all real (English) words, but thrown together to create nonsense.

Fakes kept appearing after that, from Manders’ fellow Zeno X artist Kees Goudzwaard, and his trompe-l'œil paintings that appear to be held together by strips of tape – he constructs a model with tape and then meticulously paints strips that give the illusion of tape.

And then the many extraordinary still lives from the collection of the Royal Academy, which at the moment have found a temporary space in the seventeenth-century mansion of the former mayor, Nicholas Rockox. How exciting to find these paintings in the sort of setting they were made for – domestic and intimate. The curators have constructed cabinets of curiosities around the building, matching the painted still lives with assemblages of rocks and stones and glass.

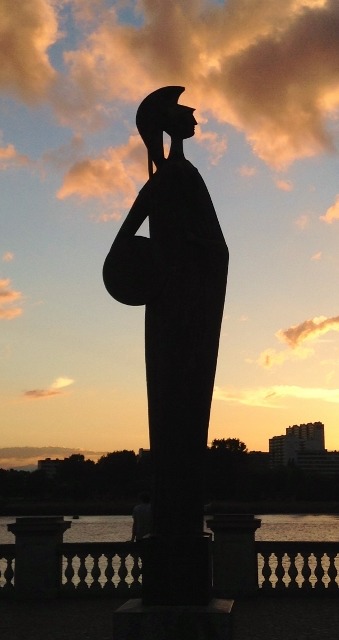

A kind of fake – at the very least, highly theatrical but at home in a place that suits theatre, the evening light gilding the spire of Our Lady.