When the photographer Tessa Traeger was a child she knew two brothers, Thomas and Godfrey Batting, first cousins of her grandmother, who ran a chemist shop in Tunbridge Wells. They remained bachelors (although both proposed at various times to Traeger’s widowed mother, who refused them). They were keen astronomers and avid collectors (and, by all accounts, great hoarders). Tom bought paintings at the local auctions, but Godfrey, an amateur photographer, collected cameras and early photographs (including the works of Dr Francis Smart and Thomas Sims). Their shop supplied all the photographers of the town with cameras, tripods, glass plates and darkroom materials.

When Traeger made the decision to train as a photographer, Godfrey was appalled, and wrote to Traeger’s mother to say that it was ‘no profession for a woman’ and that she should keep it as a ‘pretty hobby’. Despite that, Godfrey left his entire collection of photographs and equipment to her, as he knew no one else in the family would want them.

That was in 1971, and although Traeger used many of the items in the collection in her work (mainly still life photography for magazines such as Vogue) she knew that the vast collection of glass negatives would need to wait until she had the time to work out what to do with them. Now in her seventies, she has begun the massive project of sorting through the negatives, creating new work. Traeger writes:

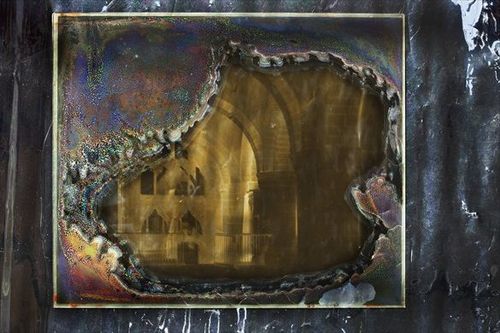

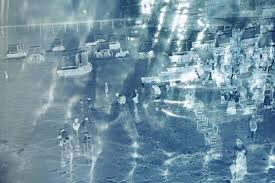

What interested me was that some of the negatives are in excellent condition and yet others were crumbling away in the most colourful chemical and fungal displays … The fungus is usually more pronounced in the dense parts of the emulsion and almost non-existent where the negative is thin, thus convincing me that it is flourishing on the silver gelatine emulsion. I started to photograph these decaying emulsions digitally … by using lighting and mirrors I was able to enter the mysterious world of the very beginnings of photography with the strangest narratives playing out before me never fully understood …

The results are the most haunting images I have seen. I’m reminded of spirit photos, which were popular in the 1860s, and which claimed to capture ghosts or spirits of the dead. People believed in them; they wanted proof that their loved ones still existed, even in ephemeral form.

But these spirit photos were created through double exposures, one of the first experiments in photographic manipulation. Traeger’s photos are not frauds, or studio inventions – they come to us through the process of decay and corruption, their subjects sometimes just visible through a haze of chemical erosion. The erosion is a rainbow of blues and greens and golds, spreading like a lovely disease; a ship sails into a cloud of evil poison, a face crazes like a broken porcelain bowl. Accident and damage, yes, but beautiful and frightening and moving in equal measure.

An early advertisement for photography admonished its new customers to Secure the Shadow, Ere the Substance Fade, Let Nature imitate what Nature made. Traeger’s project is not so much about securing the shadow before the substance fades, as showing that fading itself. Her new photos from the old negatives remind us of our own mortality, how even science is fallible, how nothing is permanent. Traeger says of her images:

They are a hymn to the layered mystery of time and light in photography, and to the miraculous work of its pioneers. I have picked my way through the lost garden of old prints and negatives, discovering new ways of seeing the forgotten walk on the beach, the boat leaving the harbour, the church door swinging wide on a vanished afternoon.

Traeger has only skimmed the surface of Godfrey’s legacy. Her project is to continue capturing what is left of these images before they fade away completely.

Tessa Traeger: Chemistry of Light is on at Purdy Hicks Gallery until 21st February:

http://www.purdyhicks.com/

Liz Jobey’s article about Traeger’s work in the FT: http://www.ft.com/cms/s/2/a417beb8-5f75-11e2-be51-00144feab49a.html#axzz2JN5WHa00