In 1945, WS Graham wrote to Sven Berlin about Alfred Wallis’s paintings: ‘It’s like the work of the angel in the man and both not knowing each other very well.’ In the following year, Graham would write his poem ‘The Voyages of Alfred Wallis’, which begins with the lines:

Worldhauled, he’s grounded on God’s great bank,

Keelheaved to Heaven, waved into boatfilled arms,

Falls his homecoming leaving that old sea testament,

Watching the restless land sail rigged alongside

Townful of shallows, gulls on the sailing roofs.

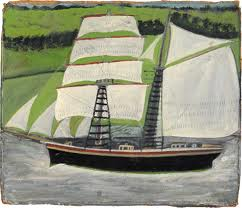

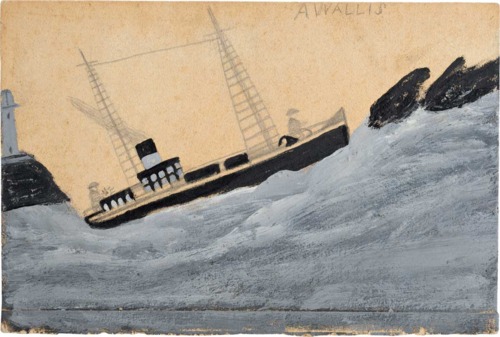

Only Graham could begin a poem with ‘worldhauled’, an invention, a conflation, heavy and labourious. In it we also see ‘wordhauled’: the idea that language is also heavy, difficult to fathom. Hard to know what Wallis might have made of it (the poem was written four years after his death); he was a man of simple words. He had no formal education. The only book he had read was the Bible (hence ‘God’s great bank, / Keelheaved to Heaven … leaving that old sea testament’). He had no training as an artist. Painting was something he took up ‘for company’ when his wife died. Everyone knows the famous story of how Ben Nicholson and Christopher Wood came upon Wallis and his paintings by accident, as they walked past his open door on Back Road West during a drawing holiday in St Ives in 1928; subsequently, how Wallis’s strange naïve pictures of boats askew, his spatially-challenged seascapes altered the course of British modernist painting. Hard to know what Wallis would have thought of his fame, the fact that his paintings have travelled farther than even a seasoned mariner could imagine, or that his rough works – mostly house paint on cardboard or wood – command five figures in auction houses (Wallis died in the poorhouse at Madron).

Graham’s poem predates the kind of fame Wallis was to achieve, although Berlin was already at work on the first serious monograph. Graham explained to Berlin in another letter that Wallis represented ‘a symbol of that energy which manifests itself in all kinds of places, so often when it is shouted for and encouraged by all the gear and disguise of “rolling eye” etc. – not appearing – and at times appearing, as in Wallis, seemingly “in spite of”.’ A typically Graham-like sentence, full of energy, stops and starts, a snaking trail of (il)logic. Kind of like Wallis’s landscapes, which are never accurate maps of a place, but are born out of ‘what used to be … what you will never see any more’ to use Wallis’s description. A life lived on the sea, already in the past when Wallis started painting, reconstructed from memory. That’s why nothing is to scale in Wallis’s paintings; apart from the fact he lacked the formal training of perspective, the huge waves ready to engulf the boat are exactly how they looked to the young mariner; the tiny houses hugging the harbor already in the distance as the schooner pushes out to sea.

Back to Graham. He had been reading the great Anglo-Saxon poem The Seafarer when he wrote his tribute to Wallis. The strong compound constructions of words come partly from this:

Sitting day-long

at an oar’s end clenched against clinging sorrow,

breast-drought I have borne, and bitternesses too.

I have coursed my keel through care-halls without end

over furled foam, I forward in the bows

through the narrowing night, numb, watching

for the cliffs we beat along.

Graham would have been deeply affected by those lines, a poet who spent his entire life next to the sea, and who understood Wallis’s great respect for its power to both lull and destroy. Graham ends his Wallis poem like this:

Falls into home his prayerspray. He’s there to lie

Seagreat and small, contrary and rare as sand.

Oils overcome and keep his inward voyage.

An Ararat shore, loud limpet stuck to its terror,

Drags home the bible keel from a returning sea

And four black shouting steerers stationed on movement

Call out arrival over the landgreat houseboat.

The ship of land with birds on seven trees

Calls out farewell like Melville talking down on

Nightfall’s devoted barque and the parable whale.

What shipcry falls? The holy families of foam

Fall into wilderness and ‘over the jasper sea’.

The gulls wade into silence. What deep seasaint

Whispered this keel out of its element?

‘Over the jasper sea’ is one of the most beautiful images in Graham. Wallis would have known it well. It comes from a hymn:

Hark tis the voice of angels

Born in a song to me

Over the fields of glory

Over the jasper sea.

Alfred Wallis: Ships and Boats is at Kettle’s Yard until 8th July

http://www.kettlesyard.co.uk/exhibitions/2012/wallis/index.php

I will be running a writing workshop looking at the influence of Wallis on poets such as Graham, Merwin, Clemo and Christopher Reid on Sunday 10th June

http://www.kettlesyard.co.uk/education/adults.html#658