In a 2008 issue of Cabinet magazine, Alan Jacobs writes of the connection between nudity and shame, beginning with Adam and Eve and their expulsion from Eden: http://www.cabinetmagazine.org/issues/31/jacobs.php. He concludes that even the strategically placed fig leaf is not enough to protect us from ‘exposure’:

Exposure cannot really be undone; what is revealed remains, in memory and image, even after it has been re-hidden. The words of the man and woman are transparently evasive. Likewise, the fig leaves merely call attention to what they are meant to hide, and in fact are another kind of evasion, another way of passing the blame, this time not to a creature or Being but to a part of the body, as though the sexual organs acted of their own accord — even though sexuality clearly plays no part in the story, in either its prohibitions or its rebellions.

In 1912, the artist Egon Schiele was arrested for sexually abusing a young girl. At the time, Schiele was painting striking portraits of some of Neulengbach’s local children, most of whom were poor and virtually homeless, and Schiele gave them shelter and a sense of purpose; this enraged the local bourgeoisie. When the police arrived at his studio to arrest him, they also seized a number of ‘pornographic’ drawings. Although the charges of sexual abuse were dropped, the judge found the artist guilty of exhibiting erotic drawings, one of which he burned publicly in front of the assembled courtroom. Schiele was imprisoned for a month.

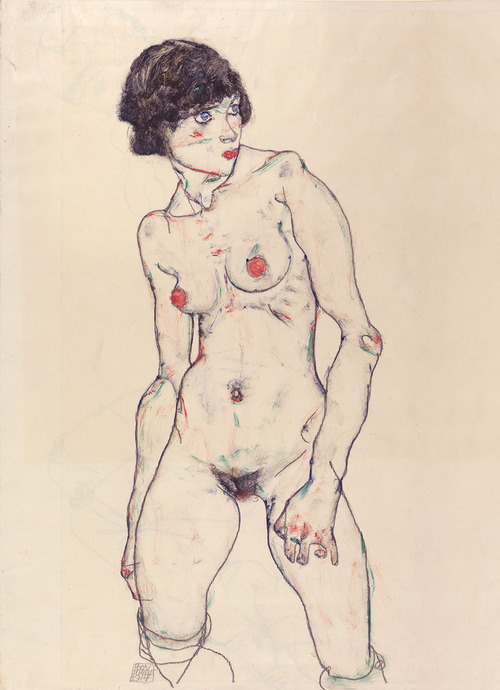

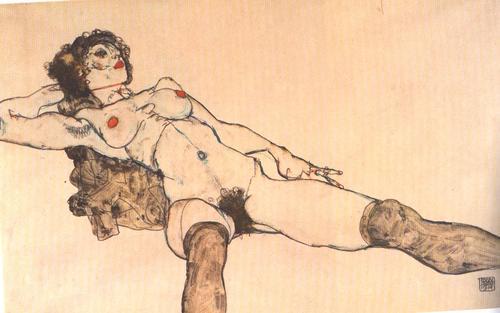

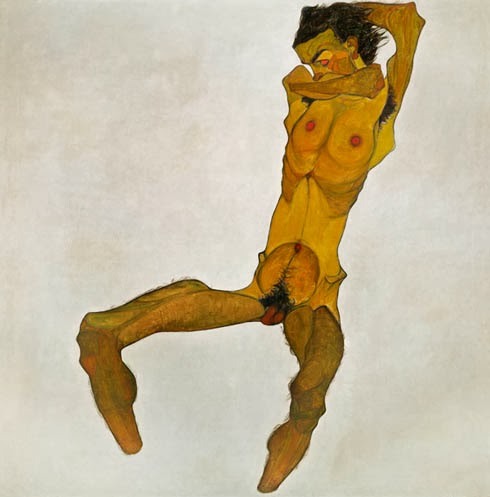

What the good people of Neulengbach really objected to was an artist who flagrantly depicted not simply the body, but its sexual organs, the part that is to blame for our sins. Schiele’s nudes are posed so that we see them from the feet upwards, as if we are crouched over them, their faces furthest from us, sometimes hidden or cropped from the drawing, so we are forced to focus on their centres of desire. They open their legs, finger their vulvas, so that we might see inside the ‘secret cave’, as John Updike said in a piece for the Schiele show at MoMA in 1997; they are not so much exposed as laid bare.

Six years after his brief imprisonment, Schiele would die at the age of 28 after contracting Spanish flu. Nearly 100 years on, his drawings are acceptable to polite society; in the pampered halls of the Courtauld, where they are currently on show, they are viewed by well-healed elderly ladies in cashmere twin sets. Of course at the beginning of the 21st century we are nearly blinded by the easy pornography that is just a mouse click away.

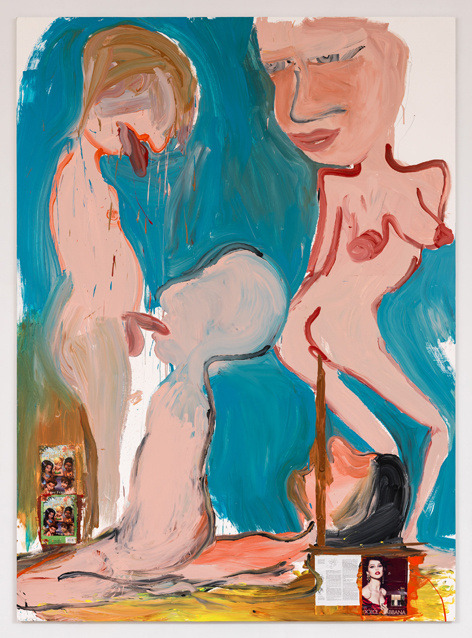

So they have lost the power to feel illicit; have they lost the power to shock? Compared to Paul McCarthy’s new paintings on display just a few miles away at Hauser and Wirth, they are pretty tame. McCarthy uses photographic images from hardcore porn, which are superimposed onto paintings of figures engaging in extreme sexual acts. His palette captures the stained hues of bodily fluids. Hauser and Wirth have blacked out the huge glass windows that face gentile Saville Row, so that entering the gallery is like entering an adult shop in Soho. McCarthy wants us to be shocked, disgusted. The paintings are ugly, his figures are grotesque. This has always been one of his motives as an artist, to present the body as a hideous object, ejecting foul liquids and odors.

But this is not Schiele’s aim. His palette often suggests bruised flesh or blood, but this is the body electric, to quote Whitman, the soul firing the skin from within. There is love in Schiele’s portraits, sexual love, but also something more – a respect for the living, breathing, procreating figure. There is also pain; the body is twisted, bent into tortured shapes. When we do catch a glimpse of a face, the expression often betrays this pain. Schiele depicts himself so often as a Christ figure, his arms outstretched, his gaunt body splayed open. His work was misunderstood, derided, burnt in public – it is not surprising he made this connection.

Somehow, even in pain and discomfort, he manages to convey beauty. It’s difficult to say why; perhaps it’s empathy; we are also naked under our clothes; our carefully constructed outer layers do not betray what’s beneath, the secret cave, the dark core, not only of our bodies, but of our emotional terrain.