On another art crawl around London with Paul Carey Kent. Paul’s walks are now so popular that sometimes twenty or more people are trailing after him (he walks fast) from one gallery to another (and

in all, he is known and greeted warmly). These walks are not just a way to see

what’s on in London, but also a way for artists and writers to meet and compare

notes, look at things together and sometimes have a good old fashioned argument

about what works and what doesn’t. Paul always plans the itinerary in advance,

and today, we are covering Kings Cross, Old Street and Bloomsbury.

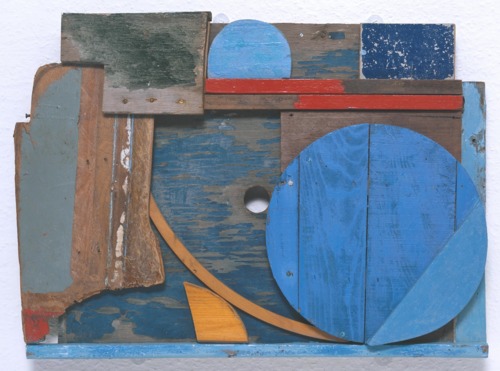

Next door to each other, in Victoria Miro and Parasol Unit respectively, are new shows from Sarah Sze and Katy Moran. A dialogue emerges between the two artists (women of roughly the same generation) centered around collecting and assembling. Although Moran’s work is on the surface more traditional, focused on painting, it’s what she crams into her small-scale canvases that is surprising. Her titles suggest the bright and kooky world of cartoons, circus, the world in all its variety, and they give a hint that the paintings are more than they appear. From a distance, they are densely patterned, energetic abstract swirls, but only when you get up close do you realize that they contain multilayered collaged bits from books and magazines, often masked or veiled by Moran’s brush. Figures emerge from the chaos of paint. Moran turns the canvas around while she’s working, so everything’s turned on its head, and there’s often no clear way in, we just need to follow her down the particular maze she leading us through.

I saw her work first at Tate St Ives some years ago, and while I liked it then, the new paintings seem to be richer, more worked, more complex – the difference between early Pound and the Cantos. Like opening an attic door and peering into the darkness and clutter, knowing you will find treasure.

Although there are silkscreen prints in Sarah Sze’s show (not so successful for me), she is primarily a sculptor, or more accurately, a compiler of installations. I was impressed with her Venice Biennale show in 2013, when she turned the United States Pavilion into the lab of a mad scientist, the strange assemblage actually snaking its way out of the building.

I loved the chaos and bustle, but also felt there was too much (and my photos capture certain individual elements I loved rather than trying to encompass the entire installation).

Here at Victoria Miro, not everything works. The installation on the lower level seems without focus. The piece is

called Still Life with Desk, and the individual elements don’t seem to add up

to much, apart from maybe trying to get at what’s in the head of the artist or

writer at the moment of creation. It’s the piece upstairs, Calendar Series,

that impressed me and reminded me of the best moments of her Venice show.

The

floor is covered in front pages from The New York Times, spanning a period of

months from July to October 2013. Sze has doctored the cover photographs,

replaced them with images that appear to be from the natural and celestial

worlds, created an assemblage of three-dimensional objects to match the photos.

The pages is lit with a series of desk lamps, each casting a small pool of

light over its chosen page in the darkened space. I think of labs, libraries,

archives, places of study or research, the object of the research perhaps

newsworthy, but odd in its isolation, its difficulty to categorise in any

satisfactory manner.

I’ve focused on those two exhibitions in detail, but we also covered the extraordinary Richard Serra show at Gagosian http://www.gagosian.com/exhibitions/richard-serra–october-11-2014 the disturbingly beautiful sculptures of David Altmejd at Modern Art http://www.modernart.net/view.html?id=1,4,1260,1261 and the gorgeous ‘tapestries’ made from old bottle caps and bits of metal by El Anatsui at the October Gallery http://www.octobergallery.co.uk/exhibitions/2015els/index.shtml . All worth catching.