As a poet, I am always interested in what artists do with text, and how, once fixed in a piece, if that text retains / contains meaning, or if meaning is obscured in some way, or lost completely. At Basel this year (my first outing to the annual art fair), there were a number of artists playing with notions of found text / collage. In the first of a series of posts on the fair, I want to focus on the humble postcard – a source for several artists.

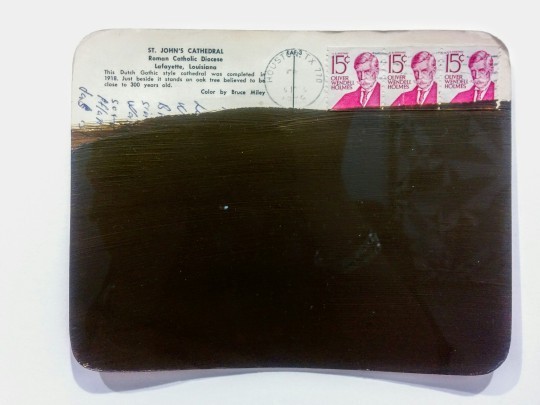

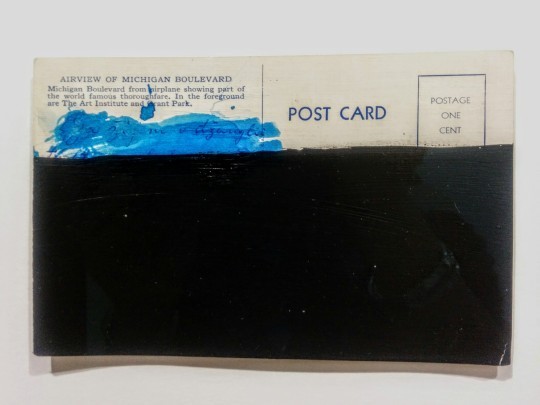

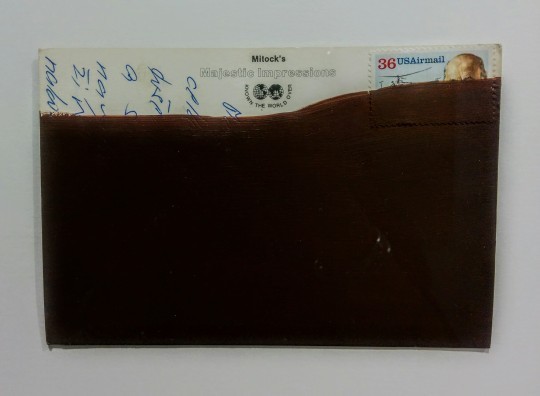

Roman Ondak is an artist concerned with process and record. I remember experiencing his installation at Tate St Ives some years ago, where he asked visitors to mark their height on the gallery wall with a pencil, then write their name and the date. The wall became an abstract drawing, a fluctuating line that looked like a tide marker (appropriate situated next to the sea). In his new piece, Messages, shown at Basel by Galerie Martin Janda, Ondak has taken a series of postcards, and redacted the writing with a sweep of heavy dark acrylic, leaving just a tantalising unreadable mass. The dark blocks are (again) like a tide consuming the text, something solid, oppressive – a tumour, a tomb. By choosing to show the cards text-side up, and then obliterating the greetings, we are left not knowing what the image is on the other side, or what the sender wanted to say about it. We are given clues – sometimes the printed text at the top reveals the location, and Ondak has preserved the stamps (I see him as a bit of a closet stamp collector); we can see all the cards shown in this selection originated in America – and weren’t sent yesterday. So notions of time, and how the past is obliterated, enter into the piece.

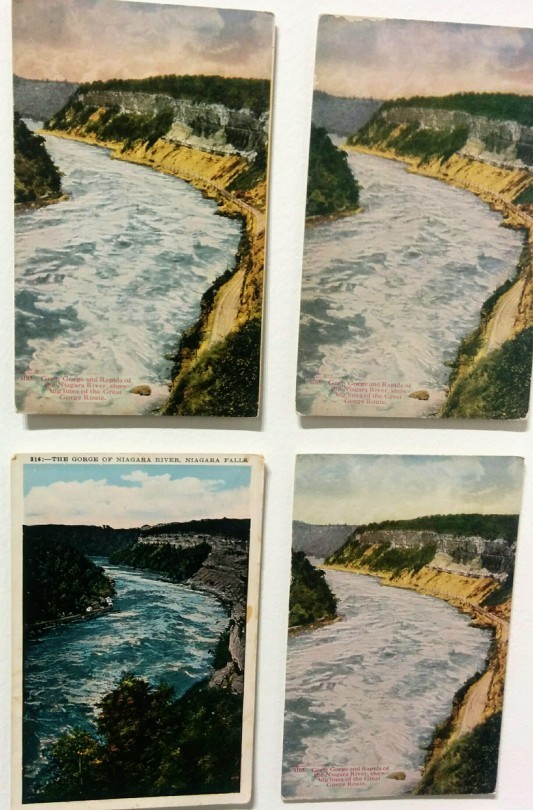

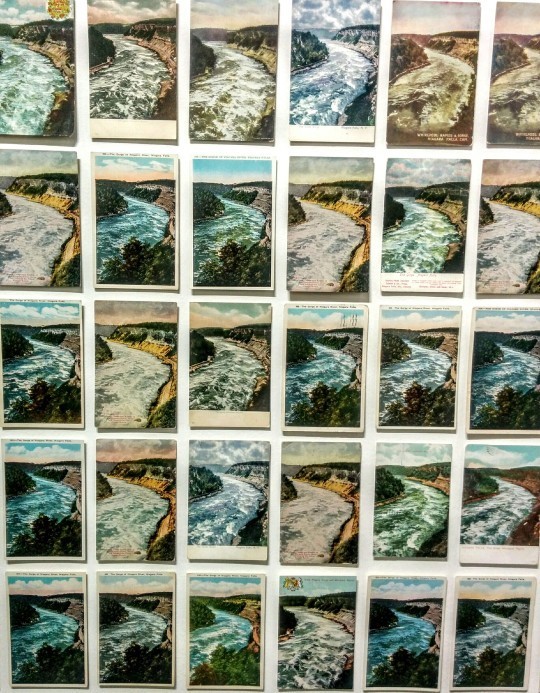

Zoe Leonard is an artist who is new to me, but looking at her other work online, she is predominantly interested in photography, exploring a theme exhaustively through a series of pictures, found and then pinned to the gallery wall. In her installation, The Gorge, on the Hauser and Wirth stand, she presents 240 postcards, all depicting a single location, the Gorge at Niagara Falls. Like Ondak’s cards, these are the kind you find stacked in boxes in antique shops, the senders and recipients long dead (and because the cards are presented face-out, we can only guess if they have been written on).

There is something both obsessive and detailed about looking at a whole wall of these, the cards often showing the same image, a body of water swirling towards a central whirlpool, like someone has pulled the plug in a bathtub. The textual element comes in the identification of the site – the font suggesting the cards are from the 50s and 60s (in addition to their faded quality). Niagara, of course, is famous as a honeymoon destination, a place of natural beauty, a tourist attraction. It sits on the border of two countries, America and Canada. It is the site of hydroelectric plants that provide power for both nations. Blondin the magician walked across the falls on a tightrope, carrying his manager on his shoulders. Marilyn Monroe and Joseph Cotton starred in the eponymous film, the strapline for which was “a raging torrent of emotion that even nature can’t control”. But there is something in the repetition that quells the torrent, creates a sense of boredom, flattens the drama.

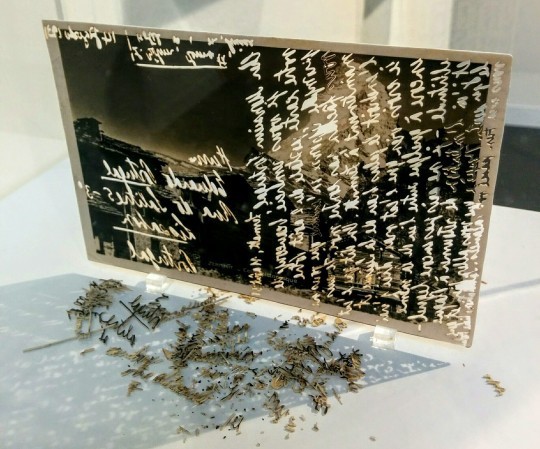

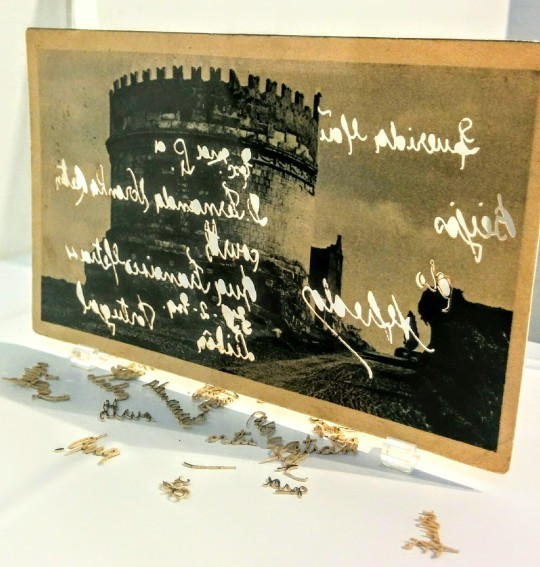

The Portuguese artist Carla Cabanas, showing at the Carlos Carvaho Gallery, takes a different approach. Her postcards become sculptures, mounted (so that the viewer can see both sides) inside a perspex box. The handwriting on each card has been carefully sliced away, letter by letter, allowing the cut-out letters to fall onto the box’s white floor. The scattered cuttings suggest some kind of damage, as if a letter-eating worm has attacked the browned surface (as with the other artists, Cabanas chooses antique postcards). Or perhaps they are a kind of extension of the image; one card depicts a little cabin at the foot of white-capped mountain, the letters like a snow drift. Although this ‘letter slicing’ preserves the text, it is still difficult to read; but I think it’s Cabanas’s way of tracing the hand that wrote the card, repeating the slow and deliberate action of writing, becoming the sender, speaking another voice.

What all three artists create with their found postcards is stasis – these rectangular vistas, written in one place and sent to another, are now halted, made into something else. The messages they transmitted have been hidden, so they are no longer vehicles of communication – just the opposite. Still, we understand what they mean, how we send them to people who are absent, with the familiar ‘wish you were here.’