There has been much debate recently (mostly between other poets) as to whether poetry is going through a renaissance or a slow death. In a recent article in The Guardian, Jackie Kay affirms that this is a wonderful time for poetry: ‘In this bleak midwinter, with the recession and bad weather, poetry may be helping us to keep body and soul together. At a time when everything is being cut, closed down, diminished and discontinued, the forecast for poetry is surprisingly fair.’

In one respect, she is right. Poetry is more visible in the broadsheets and on radio and television cultural review programmes (although still the poor relation to fiction), and poets are the recipients of high-profile prizes. But why should that be surprising?! Why do we still need to make excuses for poetry’s existence, and make poetry more palatable to people by telling them how good it will make them feel?

For those of us on the inside, we have been aware of small surges of media interest when there is something ‘interesting’ to report in the poetry world (and what is interesting to the broadsheets is hardly ever the poetry itself). It is still not clear to me, as a poet, how many people out there read poetry (especially those who are not poets themselves) and for what purpose? Is poetry’s purpose ‘to keep body and soul together’? Or is its purpose to challenge the reader in some way, to unsettle, to alter his / her thinking? Can it do both?

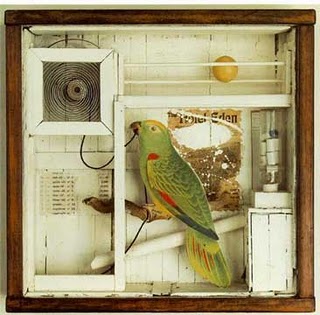

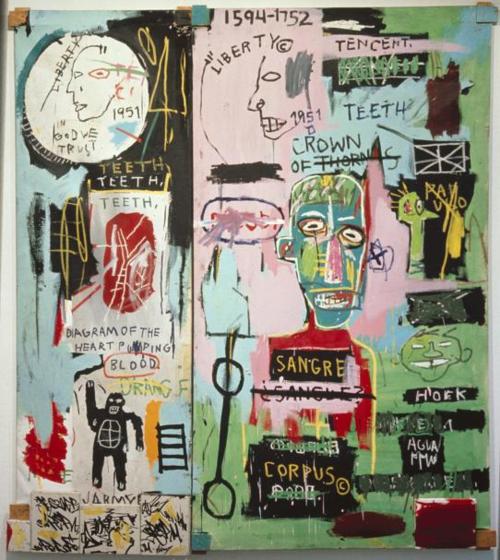

Some poets engaged in this current debate feel that poetry (more specifically, poetry in the UK) is going through a conservative period. Although I don’t disagree, I wonder if there has always been a chasm between practitioners’ interests and public reception. Although the Turner Prize is a well-established and reputable award in the art world, every year we go through the predictable tabloid jibes and knee-jerk outrage. Is it really art? Should it get public funding? Instead of trying to understand something which appears to be difficult or challenging, it’s easier (and more fun) to ridicule it.

Not to say that poetry gets that sort of public attention (possibly for financial reasons). Even in this so-called renaissance, I suspect it is still a fairly small percentage of the population who read contemporary poetry, compared to the number of people who attend contemporary art exhibitions. But why should this be? I went back to Randall Jarrell’s excellent essay ‘The Obscurity of the Poet’ and was unsurprised to find that his piece, written in 1950, sadly has not dated, and some of what he says could be said to be true today.

Jarrell’s main argument is that not just modern poetry, but all poetry, could be considered obscure through sheer neglect. He laments the fact that even educated readers no longer make the effort to read poetry, and because they are out of the habit of reading poetry, and because they view poetry as “obscure”, they assume it is therefore “difficult”.

The truth of the matter is that some poetry is difficult. Some poetry, like some art, is meant to be difficult and unsettling and provoking; it’s not meant to make us feel warm and fuzzy inside. But something that challenges and upsets us can also be affirming, in that suddenly we see the world differently, sometimes more clearly.

So instead of saying how wonderful it is that people are bothering to notice poetry at all, shouldn’t the media (and poets who act as spokespeople for other poets in the media) focus on why poetry is important, and not just as a salve for the soul?

I’ll leave the last word to Randall Jarrell:

“Art matters not merely because it is the most magnificent ornament and the most nearly unfailing occupation of our lives, but because it is life itself. From Christ to Freud we have believed that, if we know the truth, the truth will set us free: art is indispensible because so much of this truth can be learned through works of art and through works of art alone — for which of us could have learned for himself what Proust and Chekhov, Hardy and Yeats and Rilke, Shakespeare and Homer learned for us?”

http://www.guardian.co.uk/theguardian/2011/jan/29/poets-poetry-stage-roar-renaissance

http://en.wikiquote.org/wiki/Randall_Jarrell#Poetry_and_the_Age_.281953.29_.5Bessays.5D