Strolling through the gardens of the Musée Rodin, I am thinking about getting older. Inevitable, seeing as it is my birthday – always a time for taking stock of the things I have yet to do, as well as the things I have done (and some I would rather forget). The sky is cloudy, there’s a light drizzle in the air, just enough to make me reach for my umbrella. Autumnal, rather than high summer. The manicured paths remind me of Last Year at Marienbad, which I’ve just seen again. The film made no sense to me when I first watched it in my twenties, but now I get it. It’s all about time – how memory is unstable, unreliable; how the mind twists narratives, creates new ones, until it is impossible to know what really happened, especially between two people with different motives towards an outcome. Some memories are like sealed rooms, like the over-decorated salons of the hotel in the film.

I move from the gardens into Rodin’s house, the Hotel Biron, a grand rococo mansion he occupied at the turn of the last century. It has a faded splendour about it, although perhaps too overly-restored to resemble the ramshackle palace that Rodin knew. Room after room of dusty nudes, all that passion stilled. Again and again the same theme: the elderly artist reaching upwards to embrace the torso of a young woman, his muse, both of them emerging from the marble or stone or clay, only half-realised. It is Pygmalion, no doubt, but also perhaps the mature Rodin, straining to hold on to the youthful Camille Claudel. Rilke, who was for many years Rodin’s assistant, and who lived with him here, said:

Rodin developed his memory into a resource that is at once reliable and always ready. During the sitting his eye sees far more than he can record at the time. He forgets none of it, and often the real work begins, drawn from the rich store of his memory, only after the model has left.

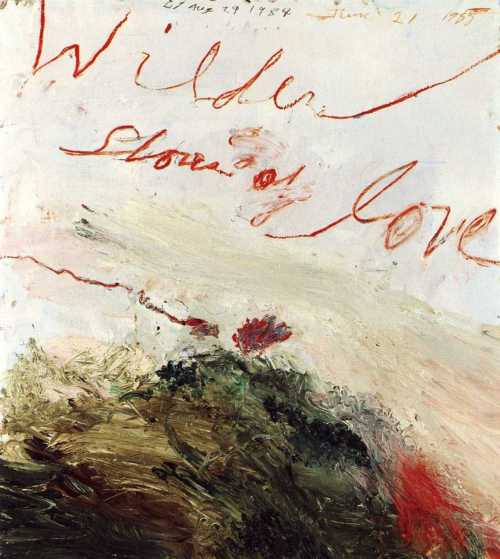

These are visions which visit the artist; he conjures them from air and sets them in stone. It was Rodin who told Rilke that in order to understand a thing you have to observe it intensely, burn it into memory. While living in the Hotel Biron, the young Rilke wrote: we transform these Things; they aren’t real, they are only the reflections upon the polished surface of our being.

In a breezy new building next to the old mansion, there are sculptures by Twombly and Giacometti and Beuys – Rodin’s successors, or as the exhibition describes them, ‘ambassadors’, I suppose because they are the bringers of the new. Their pieces sit alongside Rodin’s and re-envigorate them, lift them from the airless salons of the Biron to make us see again how modern they are. But what I find most moving is a corridor of Rodin’s studies for various busts, the heads of the great and the good awaiting commemoration, running alongside Ugo Rondinone’s Diary of Clouds, amorphous lumps of clay sitting side by side in pigeonholes which as you walk alongside them, take on moving, altering shapes.

Something about these busts to be set in stone next to the embodiment of clouds drives home this idea of the haze of memory that we increasingly occupy with age. The longer we live, the more experiences we need to store and process, and eventually pull out of ourselves to set down in whatever form we find to record them.