St Ives remains with me even now I’ve returned to the urban hub of Stockwell – the hard beauty of the landscape matched by the clarity of the artists who depicted it. So with the landscape still very present, I was saddened to read of the passing on Sunday of Breon O’Casey, one of the last of the generation of St Ives artists apprenticed to Hepworth at Trewyn. It is of particular interest to me that O’Casey came from a literary background – his father was the playwright Sean O’Casey, a contemporary of Yeats. It is perhaps too easy then to say that his paintings have the feeling of small moments arrested in time: birds captured mid-flight, landscapes reduced to the elemental (a field in spring, a group of circles resembling a cairn or pagan stones, a constellation suspended in a night time sky). There is the exuberance of the French painters he loved, Braque and Matisse, but in the restrained and earthy palette of the Penwith School.

It was only a few months ago that I went to a show of his work at Somerset House. I didn’t actually know it was on; I’d just come from the Courtauld where there was a show of Cezanne’s sketches for The Card Players (an interesting transition, as it happens). It was a bleak winter day, flat grey and featureless; the sort of day you get in London in January and February, when one day blends into the next and seems to go on forever, and you are just waiting for a small sign of spring. And O’Casey cheered me, with his simple birds and flat squares of pure colour – the sort of painting that looks simple enough (well, maybe to those who can’t paint) but which is pared down and spare and studied, like a poem by Charles Simic. Difficult to accomplish without being twee or shallow. But O’Casey’s work is resonant, meaningful.

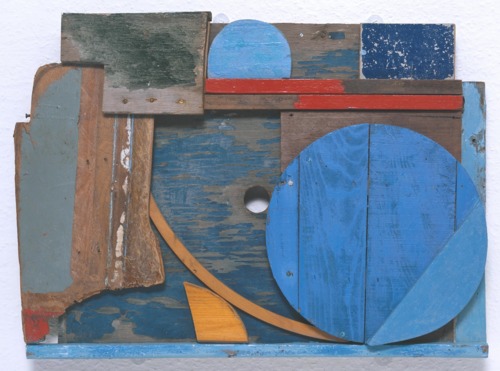

Take for example this painting, one of his many stylised depictions of birds, the title of which is Dark Blue Square. In that title there is a statement about proportion, measurement; I think of the way the sky is viewed from the ground, slivered between buildings or trees. It is a portion of sky, like the painter’s own patch. But then it appears in the bottom left of the picture, not at the top as we’d expect, so maybe our bird is swooping over a lake or reservoir. There is a paler shade of blue just touching its body – a shadow, a memory of light. The two brown columns that hold it are like tree trunks, or legs. A simple juxtaposition of shapes and colours, the colours simplified to brown, white, blue. But it’s the blue O’Casey wants us to focus on, bright and vital against the dark brown, the bird just passing through.

It’s like the last soldiers of the Great War, all those artists of that generation passing. They brought us modernism, which might feel like old hat now, but they were pioneers then (with Hepworth cracking the whip). And the work still feels valid and exciting.