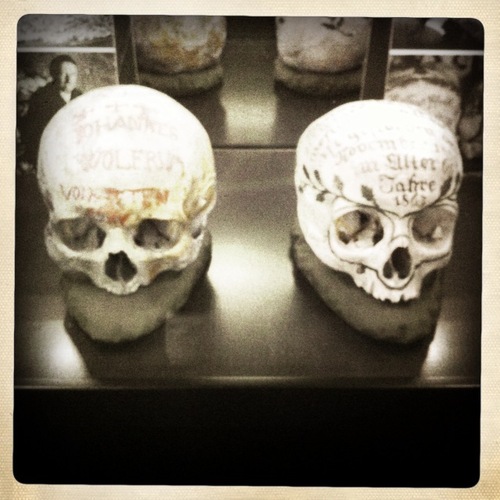

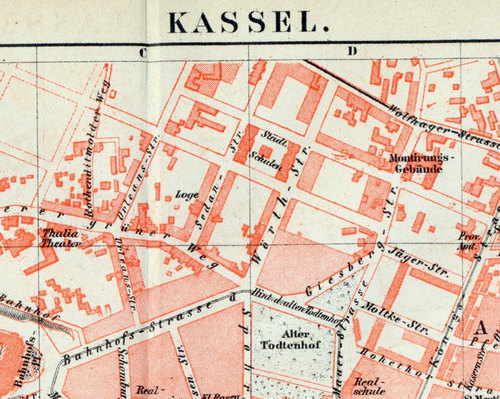

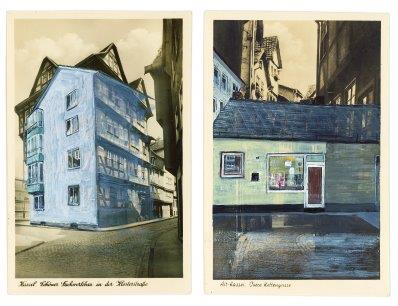

One of the great highlights of my recent trip to Kassel was a visit to the Museum für Sepulkralkultur, which is, surprisingly, a bright and airy modern building housing the most incredible collection of objects associated with death, funeral practice and mourning rites. How pleasant it was, as the sunlight streamed through the windows, to be walking amongst coffins and skulls, so beautifully preserved and cased, like precious objects. Because these things are precious, they are the stuff of us.

The Encyclopedia of Death and Dying (a truly wonderful internet resource) says this about the phenomena of the ‘death museum’:

The fact that the museums are relatively new or still in their founding or building phases seems to indicate a changing attitude toward death and dying. Questions about dying with dignity, modern forms of funeral services, or an adequate way of mourning and remembrance are more insistent in the twenty-first century than they were in the 1980 … These museums primarily foster a culture-historical approach related to the public interest in history, culture, and the arts. Therefore, collections and exhibitions focus strongly on the impressive examples of funeral and cemetery culture, pictorial documents of these events, and curiosities.

But the idea of a museum of funeral culture would have come as no surprise to Sir Thomas Browne, the seventeenth century physician and philosopher, whose essay Urne-Buriall is still one of the most eloquent and moving considerations on the disposal of human remains:

When the Funerall pyre was out, and the last valediction was over, men took a lasting adieu of their interred Friends, little expecting the curiosity of future ages should comment upon their ashes, and having no old experience of the duration of their Reliques, held no opinion of such after considerations.

But who knows the fate of his bones, or how often he is to be buried? Who hath the Oracle of his ashes, or whether they are to be scattered? The Reliques of many lie like the ruines of Pompeys, in all parts of the earth; And when they arrive at your hands, theses may seem to have wandered far, who in a direct and Meridian Travell, have but few miles of known Earth between your self and the Pole.

The way Browne introduces his subject in those opening lines moves his readers from a consideration of ‘men’, i.e. ‘mankind’, through a series of rhetorical questions, to face themselves, through his direct second-person address, as he asks them to imagine holding the relics of the dead, like Hamlet holding Yorick’s skull.

Thus, the museum of death is a place that each of us should visit, not only as a way of coming to terms with our own fate, but as a way of preserving those who have come before. In my previous posts, I have mentioned how Kassel is a place that never lets us forget the past, and so perhaps it is a particularly appropriate location not only for such thoughts, but also for a building that gathers historical and cultural archives about how we honour the dead, established for the purposes of education and research. We will never be able to examine the subject completely dispassionately (as, apart from birth, it is the one thing that all of us will share and experience) but instead of living in fear of death, perhaps we can make use of it, as Browne says:

to preserve the living, and make the dead to live, to keep men out of their Urnes, and discourse of humane fragments in them, is not impertinent unto our profession; whose study is life and death, who daily behold examples of mortality, and of all men least need artificial memento’s, or coffins by our bed side, to minde us of our graves.

http://www.deathreference.com/index.html

http://www.sepulkralmuseum.de/en/home1.html

photos by Amy Stein

There are no words to describe the beauty of Skye.

There are no words to describe the beauty of Skye.