One of my favourite books, In Ruins, considers our perpetual fascination and joy at the sight of a crumbled wall or toppled tower. Its author, the art historian Christopher Woodward, writes:

When we contemplate ruins, we contemplate our own future. To statesmen, ruins predict the fall of Empires, and to philosophers the futility of mortal man’s aspirations. To a poet, the decay of a monument represents the dissolution of the individual ego in the flow of Time; to a painter or architect, the fragments of a stupendous antiquity call into question the purpose of their art. Why struggle with a brush or chisel to create the beauty of wholeness when far greater works have been destroyed by Time?

Yet in the last hundred years, perhaps since the notion of Total War was born, we are far more likely to rip it up and start again. It was certainly necessary to rebuild from scratch in the wake of bombs that destroyed entire cities (as evidenced in my recent trip to Kassel). Those parts of London which were particularly targeted are conspicuous in their uniform 60s architecture – the Elephant and Castle immediately springs to mind. But the recent (and completely brilliant) BBC documentary The History of Our Streets also told of a desire on the part of local councils to sweep away the old and replace it with the new (sort of like Mussolini’s plans for Rome). Blocks and blocks of perfectly sturdy Victorian terraces were demolished to make way for modern tower blocks (a number of which have already been condemned and torn down, while Victorian housing steadfastly remains standing). It was the Poet Laureate of the day, Sir John Betjeman, who spearheaded the twentieth-century campaign to save older buildings of architectural merit from the wrecking ball. The organisation that he started, SPAB (the Society for the Preservation of Ancient Buildings) continues his work to this day by assigning listed status to buildings in an effort to protect them for the future.

I’m not saying that old is always necessarily better, but more that sometimes it is valuable to remember what came before. The character of London, that mix of ancient and modern, was to a large degree, determined by where the bombs fell, but it usefully shows us who were are and who we were at the same time.

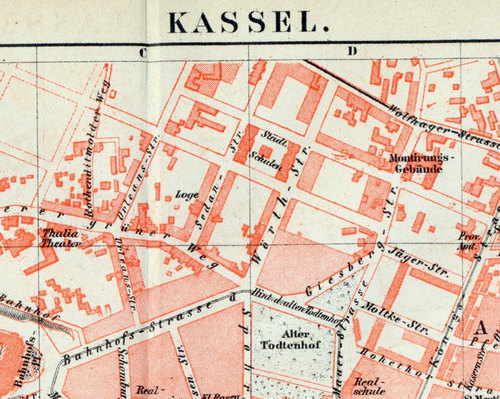

Back to Kassel, where that character is harder to determine. As I mentioned in my last post, 90% of the city centre was annihilated, and so there was little left standing to preserve. Although the Fridericianum was completely rebuilt in 18th century-style, the impulse was to start from scratch, and so most of the centre is permanently locked in the 60s and 70s.

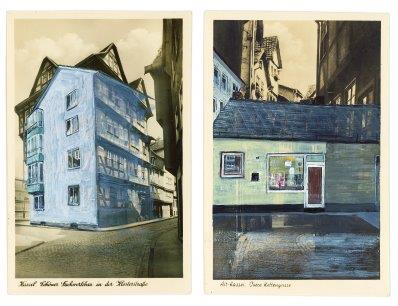

Which is why Tacita Dean’s piece for Documenta 13 is so fascinating. As a long-standing resident of Berlin, Dean understands the impulse to start again (although Berlin, as I’ve said before, is a great city for the recycling of buildings, and you can find traces of the Wall marked in a discreet pathway beneath your feet). She has collected a number of pre-war postcards of Kassel, showing views of the old city centre, and has painted over them to show what stands there now. In my previous post, I talked about my friend Siriol Troup and how she likes to go round Kassel with a guidebook from 1901; Dean’s piece stems from a similar desire – to understand what came before, what it was like before your time.

To understand what it was like before your time is the second dimension to the piece. Dean then sent the cards by post to Kabul c/o Jolyon Leslie, the former CEO of the Aga Khan Trust for Culture. But the project is dedicated to another Jolyon, her late father. So she sent postcards of a place which no longer exists because of war destruction to a place which is currently going through what Kassel went through nearly seventy years ago; and addressed them to a man who shares a name with the father of the artist, who is no longer alive to receive them. The piece seems then to be about inheritance, noting things that have disappeared so that future generations do not forget to record what they have before it is gone.

A related installation is about bringing Kabul to Kassel, having already sent Kassel to Kabul. In the staircase of an ex-finance office (an older building, possibly from the twenties, which survived the bombs) Dean has installed a large panorama of the rivers and mountains of Afghanistan. These are drawn on chalk on large blackboards, so that the viewer could be a child in a classroom learning of this distant place which is being obliterated from the map (I remember a similar experience when I was growing up, learning about Viet Nam while the country in which I lived was destroying it). The chalkboards could also represent the fleeting nature of the landscape (which, like chalk, can be wiped away), although there is something more permanent about a mountain or a river than about man’s built environment, which can be toppled with one smart bomb.

Dean’s double work for Documenta is one of the most moving and beautiful I have seen recently which represents both our time and the past, and the desire to preserve and record, even those things which have already left us.

More images of Dean’s piece here: http://www.contemporaryartdaily.com/2012/06/documenta-13-tacita-dean/

Photos by Amy Stein and Andrew Lindesay