I’m a guest on the Royal Academy’s blog today, talking about the two-way influence of poetry and Joseph Cornell, ahead of my course Containing the World in Words

https://www.royalacademy.org.uk/article/joseph-cornell-poetry

© Tamar Yoseloff 2024

I’m a guest on the Royal Academy’s blog today, talking about the two-way influence of poetry and Joseph Cornell, ahead of my course Containing the World in Words

https://www.royalacademy.org.uk/article/joseph-cornell-poetry

Last week was a busy one. But I’m always

happy to be busy when it means new books are finding their way into the world.

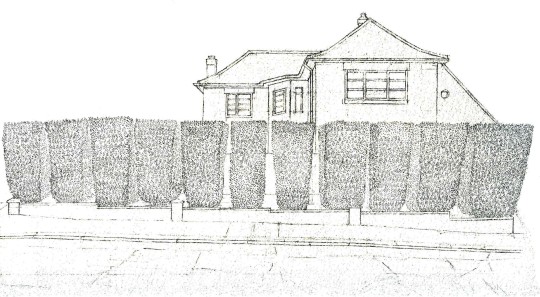

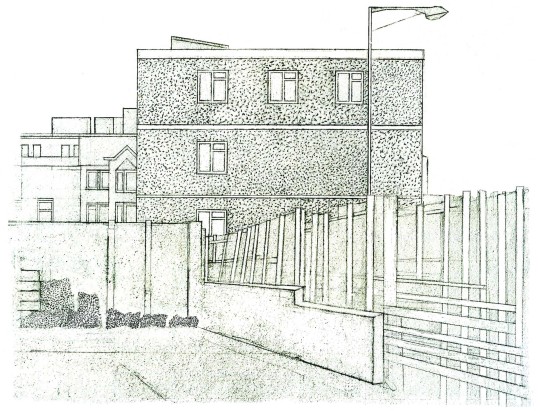

On Monday we celebrated the opening of David Harker’s new show at the Poetry Café (he’s in the picture with art critic and blogger Paul Carey Kent). Readers will know that my association with David began a couple of years ago, and we have been collaborating ever since. It made sense to bring the poems I’ve been writing together with the images that have inspired them, and so Monday also marked the publication of our book, Nowheres.

The title is taken from one of the poems that describes its location, somewhere along a motorway in Andalucía, as ‘the definition of nowhere’. But then a lot of the locations in David’s drawings could be described similarly, neither here nor there, possibly on the way to somewhere else, but often not destinations in themselves. David and I have remarked how the new drawings are unpopulated, but the once-presence of people is often indicated, through graffiti, or a well-manicured hedge, or a hole in a fence. David’s locations are always man-made environments, often on the point of collapse (or past it, in the case of his drawings of ruins). In writing my poems, I had other poetic nowheres in my head: the disused shed; the platform at Adlestrop; Stevens’ great structure, now a minor house. These are all images that attract me for making somewhere of nowhere, just by suggesting that these are places where people once came to make something, and somehow failed. The poem is the attempt perhaps to make something out of nothing, to suggest there is still hope.

Anyhow, David makes very beautiful drawings

out of these nowhere places, and the book is an equally beautiful production of

our combined efforts.

On Thursday, Vici and I launched the latest

Hercules Editions book, Silents by

Claire Crowther. Claire’s poetry taps into the misty world of early film, its

shadows and flickery movements, its voiceless wide-eyed expressions. The launch

was at the incredible Cinema Museum, the home of the Ronald Grant Archive,

which we raided for the book’s images.

The Museum is like one of those dreams you

might have of walking through a haunted house at night with the ghosts of the

past hot on your heels. The place is cluttered with old cinema marquees and

lobby cards, black and white stills of B-list actresses very nearly forgotten,

Technicolor posters. The building was once the Lambeth Workhouse, and the child

Charlie Chaplin, the original little tramp, was briefly a resident, when his

mother was too destitute to afford their lodgings nearby in Kennington.

Before the reading, we showed Nosferatu on the big screen in the main

hall. I was envisioning it as something to have on in the background, but I was

pleasantly surprised to see at least half our guests sitting in rapt attention

as Max

Schreck mounted the

stairs, his elongated claws reaching out for his victim. The pianist Alcyona

Mick played along to the film, and made us all yearn for the days when the organ would rise from the floor of the cinema as if by magic (familiar from

films about the golden age of film).

It was the perfect venue for Claire’s unsettling and strange poems.

Both books are now well and truly launched. Nowheres is available from the Poetry Café for the duration of David’s show: https://poetrysociety.org.uk/poetry-cafe/exh/

Silents is available from the Hercules website: www.herculeseditions.com

David and I will be running a cross-disciplinary workshop at the Poetry Café on 6th June: http://www.poetryschool.com/courses-workshops/face-to-face/crossing-the-line.php

There is an episode in Ben Lerner’s novel Leaving the Atocha Station in which the

American protagonist is taken to Granada by Isabel, a love interest. For

reasons to do with the complexity of their relationship, they spend a night in

the city then leave abruptly, without visiting the Alhambra – their intended

destination. The protagonist wonders if he would be ‘the only American in

history who visited Granada without seeing the Alhambra.’

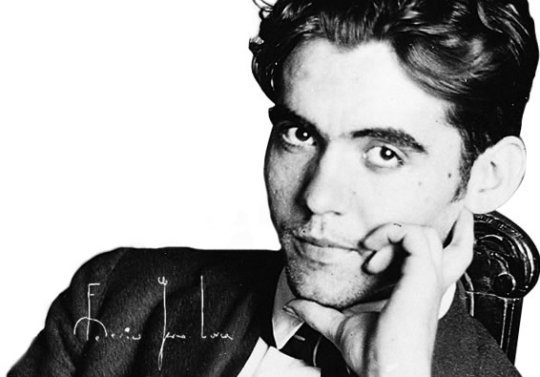

I may be one of the few poets who visited Granada without seeing Lorca,

or at least his home. We dutifully travelled out to Fuente Vaqueros,

his birthplace and the site of a museum dedicated to his life and work, only to

find it closed for the 1 de mayo festivo. I was at least

heartened to discover a few Spanish tourists also attempting to ring the bell, and

nodding in solidarity over our mutually missed experience, before sloping away

in frustration.

However, Lorca’s presence shaped the visit. Like

Lanyon’s view of Cornwall, it often takes someone born into a landscape to show

it to you properly. A far cry from the elaborate prose of Washington Irving,

Lorca’s Granada is a place of simplicity and strangeness, of ‘deep and crooked

light’, heavy with ‘putrefying perfumes’ where death and life occupy a single

location. Nature is always busy and noisy, the frogs ‘the muezzins of shadow’.

In the Albayzín

and the hills of Sacromonte, it is easy to find his ancient streets preserved.

In Manuel de Falla’s house, we even found a chair in which the

poet sat to hear the first performance of one of the composer’s works.

There is

a lot of blood in Lorca’s poems, and I noticed those sharp gasps of red

everywhere, in the soil itself, in the traditional costumes (because of the

festivo, women all over town were kitted out in full flamenco gear), in the

paintings of saints embracing their martyrdom adorning the monasteries.

It is

difficult to remember that this place of extraordinary beauty has always been a

place of dispute, from the violent removals of Islamic kings jostling for

power; to the Inquisition, and the expulsion of the Muslims and Jews under

Catholic rule; to the Civil War, and Lorca’s murder somewhere near the sleepy

village of Viznar.

I may not have made the pilgrimage to Lorca’s house

that I’d been planning (at least I stood outside the door!) but I will be able

to envision his landscape now when I read his poems. And visiting during the festivo,

this poem in particular (translated by Jerome Rothenberg) captures exactly the

mood:

Floating Bridges

Oh what a crush of people

invisible reborn

make their way to into this garden

for their eternal rest!

Every step we take on earth

brings us to a new world.

Every foot supported

on a floating bridge.

And I know there is no

straight road in this world –

only a giant labyrinth

of intersecting crossroads.

And steadily our feet

keep walking & creating

– Like enormous fans –

These roads in embryo.

Oh garden of white

theories! garden

of all I am not, all

I could & should have been!

Vita Sackville West called it ‘a sinister little flower, in the mournful colour of decay’. The poet and botanist Geoffrey Grigson referred to them as ‘snaky, deadly beauties’. Anne Ridler described it as ‘delicate’ and ‘rare’: ‘You enter creeping, like the snake / You’re named for . . . ‘. Denise Levertov would have it as ‘our talisman in sorrow’. It has been called the Leper Lily, Lazarus Bell, Drooping Tulip, Bloody Warrior, Turk’s Head and the Mournful Bell of Sodom. It’s dramatic, with its curved amethyst hood, like a fin de siècle heroine. And poisonous, the Lucrezia Borgia of the flower world.

During

our week in the Dordogne, as the guests of Anne Berkeley, Sue Rose and I were

treated to the sight of a field dotted with snakes head fritillaries. Even

there, where they are more abundant than at home (introduced into the English

garden sometime in the eighteenth century) we had to search, skirting the paths

along the Dronne, attempting to spot bright dashes of purple, like rare jewels

in the grass. But there was a satisfaction in the hunt; eventually spotting

them, flamboyant and shy at the same time, in the early April sun. We had

missed their full blooming, caught them as they were on their way out, not to

come again until next spring. Poisonous, beautiful and fleeting.

It’s a bit like writing, which we had assembled to do together (this activity we normally practice in isolation). Somehow going away with other writers provides a kind of team spirit – there is nothing so inspiring (and daunting) as the sight of another writer getting down to business, happily tapping away on her laptop. But maybe not so odd – after all, the poem is something you create for yourself first, but then you are encouraged to share it, to allow the reader to become part of the bargain you strike when you first put pen to paper (or fingers to laptop).

I

have spoken here before about the freedom of writing away from home, how the

anxieties and tasks of every day life are briefly forgotten when you are

somewhere else. The joy of writing is that you need very little in the way of

equipment to engage in it, and you can easily move from one place to another

where there are fewer distractions (apart from the noisy nightingale, who

seemed to be at it for much of the day as well).

Back

home, it seemed I wasn’t quite finished with my fritillary spotting. As they

had already departed my garden (where I’ve planted a small pot of them – not

quite as exciting as finding them in the wild), I was thrilled to find a lone

one among the cowslips in the churchyard at Tudeley in Kent. And here, another curious

transplant – stained glass windows by Chagall in the medieval church. My friend

Lynne Rees and I had made an excursion to see them, and the sun shone on our

efforts.

Chagall was initially commissioned to design a window in memory of Sarah D'Avigdor-Goldsmid, who died in a boating accident in 1963. He subsequently designed the rest, making it the only church in the world to have all its windows by Chagall; the final one was installed in 1985, the year the artist died at the age of 98.

They are perfect in their surprising setting; exuberant, bright, but also somberly moving. It seemed appropriate to be there, back in my adopted country, looking at the work of a fellow Russian Jewish émigré, who made his home in France, where I’d just been.

And so we bloom where we are planted …

Occasionally people ask me about the derivation of the name of this blog. Regrettably, I can’t take credit – it’s the title of a poem by Wallace Stevens. When I first started, I posted a

statement on why I chose it:

In his poem ‘Invective Against Swans’, Stevens has a dig at those lovely birds, bringing them down a peg by calling them ‘ganders’ (which are actually male geese), dismissing their ‘bland motions’. I suspect Stevens had no serious gripe against swans; nor do I. They are decorative, they transform a landscape into a painting, they make me hum Tchaikovsky to myself. But stick them into a poem, specifically a contemporary poem, and they become a metaphor for all that is trite and precious. And that’s Stevens’ beef, all those ‘white feathers’ and ‘chilly chariots’. There he was, facing a newish century, a brave new world that had shaken itself out of a war; a new poet trying to find a new way of saying things. He is railing against the grandiose, the clichéd, the humourless. Never one to miss a joke: ‘gander’ is also colloquial in boon dock Florida for ‘a quick glance’, as in ‘get a gander of that’; also colloquial for the village simpleton, as idiotic as a goose. And as we’re talking specifically about a ‘male goose’, could the poet be referring back to himself, possibly to all his fellow bards (how close that is to ‘birds’!) as well?

I suppose my aim in this blog has always been to explain my notion of what I find beautiful in the world, which is not always typical (swans being an easy measure of ‘typical beauty’). Stevens has been one of my guides. His work has made me interrogate image and language. When I was thinking what to call this collection of random thoughts, he seemed to provide the right phrase. I am not the only poet to reference Stevens in this way. One of my favourite contemporary presses is Shearsman, its name taken from a line in ‘The Man with the Blue Guitar’: ‘The man bent over his guitar / A shearsman of sorts.’ The musician becoming a maker (a shearsman being a cutter of cloth), as is the painter (Picasso) or the poet (Stevens). The poem is a manifesto for the making of art, and therefore the shearsman is an appropriate symbol for a press that espouses the made poem, an object that sometimes challenges convention, like Stevens, like Picasso.

I have recently discovered that an electronic duo based in Brussels have named themselves after one of my poems. Here is a link to Mannequins on 7th Street:

https://soundcloud.com/mannequinson7thstreet

On their site, they talk about the name as an ambient reference to the general chaos of city life, something they attempt to reflect in their music. Ironically, the poem came not from the place itself, but from a drawing by Anthony Eyton; so like the shearsman of Stevens’ poem, who presides over poet, painter and musician, the title Tony gave his drawing now radiates out over all of us.

It makes me think too of how some artists have the right name. Sometimes a name even becomes an adjective for an artist’s practice; to say a poem is Plathian is to say its images are dark and strange, its language clipped and sparse. Plath’s name is monosyllabic, it sounds like the noise that a pebble makes hitting the water. She loved the assonance of soft ‘a’s.

I have a name that is invented. The story, although intensely personal to me, is really a common one: my grandparents arrived at the port of Galveston, Texas, with their papers in Cyrillic and not a word of English. The desk clerk asked them to say their name aloud, and he took it down as he heard it. YO-SEL-OFF. As a poet, I value the strange name that no one can spell, that was made up on the spot, that makes me sound rare and exotic, the grandchild of Russian immigrants who went to a new country to make a new life. After all, we are always inventing ourselves, making up names for what we create.