Last week was a busy one. But I’m always

happy to be busy when it means new books are finding their way into the world.

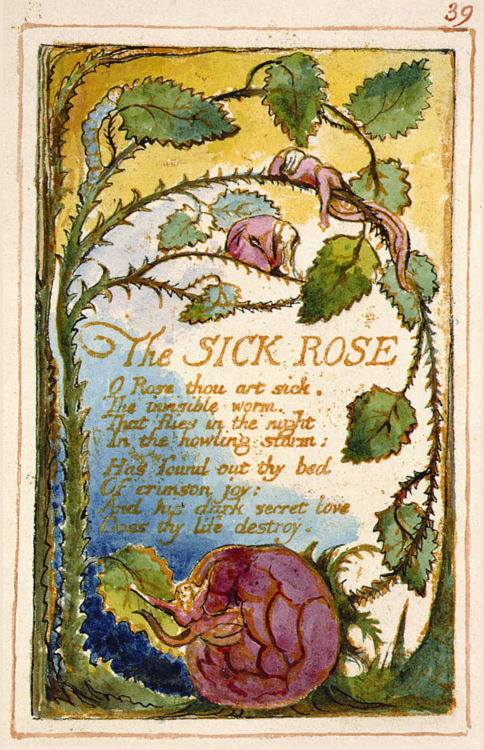

On Monday we celebrated the opening of David Harker’s new show at the Poetry Café (he’s in the picture with art critic and blogger Paul Carey Kent). Readers will know that my association with David began a couple of years ago, and we have been collaborating ever since. It made sense to bring the poems I’ve been writing together with the images that have inspired them, and so Monday also marked the publication of our book, Nowheres.

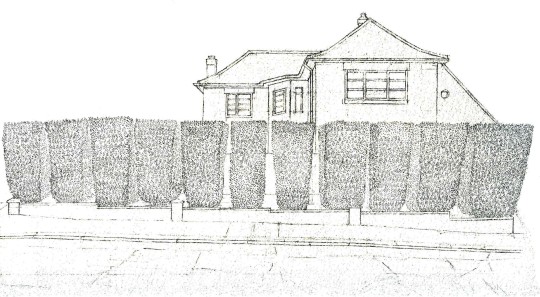

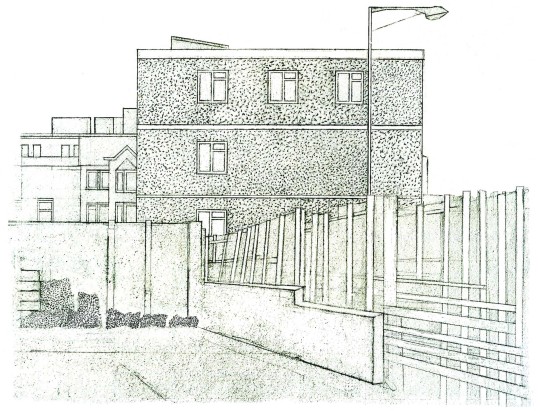

The title is taken from one of the poems that describes its location, somewhere along a motorway in Andalucía, as ‘the definition of nowhere’. But then a lot of the locations in David’s drawings could be described similarly, neither here nor there, possibly on the way to somewhere else, but often not destinations in themselves. David and I have remarked how the new drawings are unpopulated, but the once-presence of people is often indicated, through graffiti, or a well-manicured hedge, or a hole in a fence. David’s locations are always man-made environments, often on the point of collapse (or past it, in the case of his drawings of ruins). In writing my poems, I had other poetic nowheres in my head: the disused shed; the platform at Adlestrop; Stevens’ great structure, now a minor house. These are all images that attract me for making somewhere of nowhere, just by suggesting that these are places where people once came to make something, and somehow failed. The poem is the attempt perhaps to make something out of nothing, to suggest there is still hope.

Anyhow, David makes very beautiful drawings

out of these nowhere places, and the book is an equally beautiful production of

our combined efforts.

On Thursday, Vici and I launched the latest

Hercules Editions book, Silents by

Claire Crowther. Claire’s poetry taps into the misty world of early film, its

shadows and flickery movements, its voiceless wide-eyed expressions. The launch

was at the incredible Cinema Museum, the home of the Ronald Grant Archive,

which we raided for the book’s images.

The Museum is like one of those dreams you

might have of walking through a haunted house at night with the ghosts of the

past hot on your heels. The place is cluttered with old cinema marquees and

lobby cards, black and white stills of B-list actresses very nearly forgotten,

Technicolor posters. The building was once the Lambeth Workhouse, and the child

Charlie Chaplin, the original little tramp, was briefly a resident, when his

mother was too destitute to afford their lodgings nearby in Kennington.

Before the reading, we showed Nosferatu on the big screen in the main

hall. I was envisioning it as something to have on in the background, but I was

pleasantly surprised to see at least half our guests sitting in rapt attention

as Max

Schreck mounted the

stairs, his elongated claws reaching out for his victim. The pianist Alcyona

Mick played along to the film, and made us all yearn for the days when the organ would rise from the floor of the cinema as if by magic (familiar from

films about the golden age of film).

It was the perfect venue for Claire’s unsettling and strange poems.

Both books are now well and truly launched. Nowheres is available from the Poetry Café for the duration of David’s show: https://poetrysociety.org.uk/poetry-cafe/exh/

Silents is available from the Hercules website: www.herculeseditions.com

David and I will be running a cross-disciplinary workshop at the Poetry Café on 6th June: http://www.poetryschool.com/courses-workshops/face-to-face/crossing-the-line.php