I have experienced Janet Cardiff’s Forty Part Motet on several occasions. The work consists of a circular arrangement of 40 speakers, each speaker playing a recording of an individual member of the Salisbury Cathedral choir singing Thomas Tallis’s Spem in allium. Visitors are invited to walk amongst the speakers seeking out single voices, to become a participant in the music, rather than simply a listener. Cardiff has said of the installation:

While listening to a concert you are normally seated in front of the choir, in traditional audience position. With this piece I want the audience to be able to experience a piece of music from the viewpoint of the singers. Every performer hears a unique mix of the piece of music. Enabling the audience to move throughout the space allows them to be intimately connected with the voices. It also reveals the piece of music as a changing construct. As well I am interested in how sound may physically construct a space in a sculptural way and how a viewer may choose a path through this physical yet virtual space.

I have heard the piece in pristine gallery spaces – at the Whitechapel in London and at the Baltic in Newcastle. The purity of the space, the absence of distractions (and the absence of human beings apart from gallery visitors – simply disembodied voices singing) has given it a particular ghostly resonance. So I was interested to see how my perception of the piece would alter hearing it in the hallowed spaces of the Cloisters, the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Medieval outpost, a gathering of French and Spanish ecclesiastical structures collected through many grand tours and bequests, and reassembled on a hill in Fort Tryon Park, overlooking the Hudson River and the bucolic shores of New Jersey.

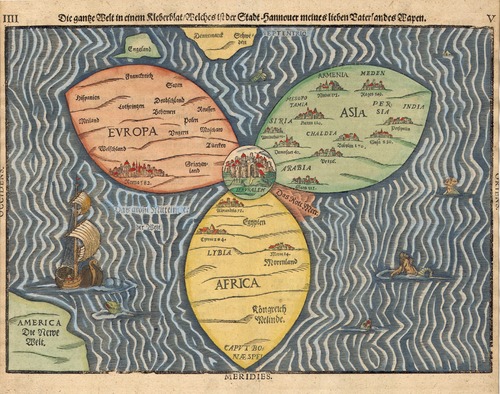

I lived in that neighbourhood, known locally as Inwood, during the summer before I moved to London. My boyfriend at the time found the sublet, attractive for its cheapness (we were both unemployed college graduates). I remember writing in a poem at the time about how the low rise 30s blocks looked like old radios. It was a proper old-style New York neighbourhood, completely untouched by gentrification, occupied by ancient Irish men, hard-up Julliard students (we had a tuba player across the courtyard from us who was not popular) and young Hispanic families. The Hispanic residents brought a bit of excitement to the place with their bright bodegas, full of votive candles depicting various saints we’d never heard of (which we used to collect and light in our kitchen), and coconut vendors, who occupied the corner near the subway. There were a lot of Haitians in the neighbourhood, and my boyfriend told me they held Voodoo ceremonies in the park on summer nights. I was never sure I believed this, until one day I found two pigeons tied together with their heads sliced off. Strange to think that the park might have been home to such rituals, and also home to the Cloisters, a little slice of Medieval Christianity in Manhattan. But that has always been the city’s gift, to be able to accommodate the community of the world in its tight grid.

Cardiff’s installation makes you forget all the clamour of the streets outside. In all the occasions I’ve experienced it, what has struck me is how it reduces the world to the moment you are experiencing it. In other pieces, Cardiff uses urban landscapes as stage sets for her narratives, but here, she wants you to forget everything else, so that the music allows you to explore internal narratives instead. And watching fellow visitors, you feel they are experiencing a similar shift, that they have forgotten where they are, and that this extraordinarily beautiful music is having a profound effect, whether they believe in God or not. In that respect, Forty Part Motet operates the same way in a pristine white space as it does in a religious setting – perhaps it works best when there are no distractions at all – but placing it in a chapel reminds us of the original source of the music, as a devotional piece. Conversely, it made me realise that for me the pure white gallery space is my place of refuge, and what I look for is that simple transaction between the artist and the viewer (or listener) that can change the way you feel about the world. I was just beginning to put those thoughts together the summer I lived in Inwood, the summer before I moved to London. I used to walk in the park and look out over the Hudson and wonder what my life in London would be like. Listening to that music, back in the Cloisters after many years, what I realised was that for me it taps into something much larger than individual or place, something unknown.

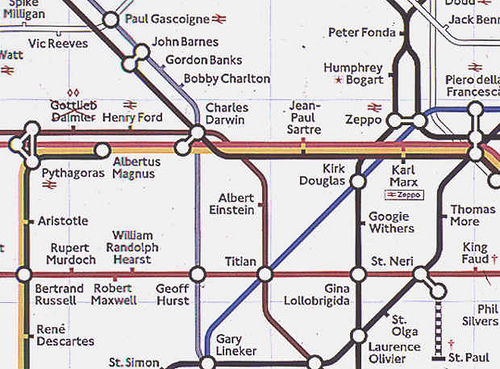

Formerly is an attempt to erect some unofficial blue plaques. The exhibition is looking lovely in its spot high over the Thames in the Poetry Library. From next week, we will be inviting visitors to create their own psychogeographical texts, based on their own wanderings, their personal maps. Watch this space.

Formerly is an attempt to erect some unofficial blue plaques. The exhibition is looking lovely in its spot high over the Thames in the Poetry Library. From next week, we will be inviting visitors to create their own psychogeographical texts, based on their own wanderings, their personal maps. Watch this space.