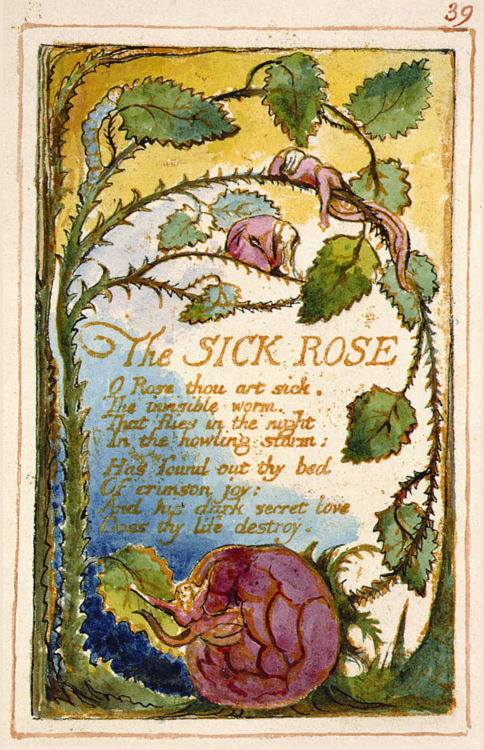

is the title of an Eavan Boland poem (and a point I wish to prove).

In that poem, Boland is walking with her husband in the woods. They come to a track that her husband identifies as a famine road, a place of forced labour and suffering. ‘Where they died, there the road ended,’ she writes:

and ends still and when I take down

the map of this island, it is never so

I can say here is

the masterful, the apt rendering of

the spherical as flat, nor

an ingenious design which persuades a curve

into a plane,

but to tell myself again that

the line which says woodland and cries hunger

and gives out among sweet pine and cypress,

and finds no horizon

will not be there.

The poem broke my heart the first time I read it, but it wasn’t until much later that I was able to find an explanation for its impact. It was at a talk by Rebecca Solnit on the subject of maps. At the time, she was embarking on a project called Infinite City, a radical remapping of her hometown, San Francisco. Her proposed ‘alternative’ maps included ones locating Butterfly Species, Murders, Zen Buddhist Centres, Queer Sites. ‘What we call places are stable locations with unstable converging forces,’ she said, and it hit me that this was a way of summing up what Boland is saying in her poem. A place can be altered by time, fate, a random meeting. These alterations are not evident, they cannot be expressed by coordinates, they are simply known and felt. One of my older students told me that as a child during the war she saw an entire London street levelled by a bomb. I could walk down that street, and to me it is another street, because it carries no personal associations, but she retains the image of the street in ruins, and nothing of its present can wipe away that past.

In the last few weeks, I’ve been thinking about this issue of ‘official’ and ‘unofficial’, ‘personal’ and ‘public’ maps, as Vici MacDonald and I have been revisiting the places we charted in our Formerly project. Our field trips took two whole days to complete, as we journeyed south, then east, crossing the river at Woolwich, heading west, then north. What struck me in our travels was how much London changes; whole blocks are toppled in the name of progress. But if you have been here long enough, the folk memory of what was there before is somehow ingrained in you. What struck me too was how some things never change; there are certain aspects, buildings, streets that connect me with strangers, fellow city dwellers, who walked the same steps and saw the same sights hundreds of years before. The official maps can tell you how to get somewhere, how to plan your route, but the unofficial ones tell you how you felt while you were doing it. Solnit spoke too about the personal map, created when one has lived in a particular city for many years. On that map are sites of liaisons and break-ups, streets of friends and lovers – a series of unofficial (and deeply internal) blue plaques.

Exhibition has now been extended until 3rd February: http://ticketing.southbankcentre.co.uk/find/literature-spoken-word/tickets/formerly-1000346

Eavan Boland poem in its entirety:

http://www.smith.edu/poetrycenter/poets/thatthescience.html

Rebecca Solnit: http://www.rebeccasolnit.com/infinitecity

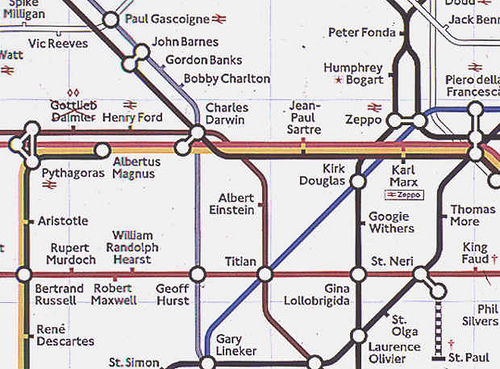

The Great Bear is an altered map of the London Underground by the artist Simon Patterson

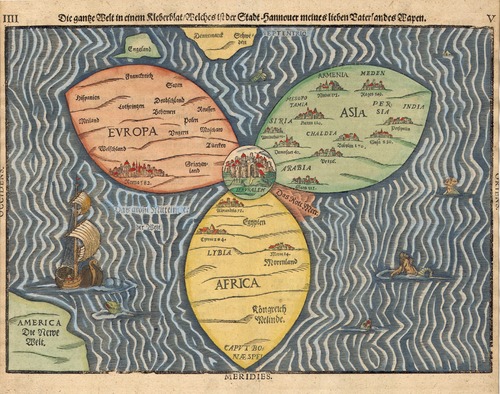

The cloverleaf map of the world, with Jerusalem at the centre, was created in 1581 by Bünting