Why is it that a pile of stones can make us so emotional? Think of the great abbeys toppled, mansions abandoned, the kind of ruin that represents the decline of the mighty and powerful. Then think of the modest shacks of Haiti razed to the ground, families picking through the pulverised remains of their homes. Or the Gaza Strip, or Basra, or Kabul, anyplace where war has created the kind of ruin which is instant and total and unsalvageable (not like the graceful ageing process of slow decline). Or the most cataclysmic, devastating and recognisable ruin of our age: the site of the former World Trade Centre in New York (I have never liked the phrase Ground Zero, which suggests that nothing was there to begin with). We encounter ruin everyday in our lives as city dwellers: empty office blocks like bulky ghosts, or crumbling houses, foreclosed or squatted. We become so accustomed to ruin as a normal state that we cease to notice it, so when a new building appears and alters the horizon, we can’t remember what was there before (although chances are we walked past it often enough). But there is still a sense of regret; these are the things we have built, and nothing is permanent, not even our efforts to make something of lasting value.

In perhaps the greatest ‘ruin’ poem of the last century, The Waste Land, Eliot gathers ‘fragments I have shored against my ruins’. The assembling of those fragments, those histories, myths, voices and places, is the poem itself, the monument he hopes will save him and his world from destruction. But in the ‘unreal city’ he portrays, destruction is present everywhere, and so what he seems to be saying is that we can gather our words around us, but nothing will stop the slow creep (sometimes immediate blow) of devastation.

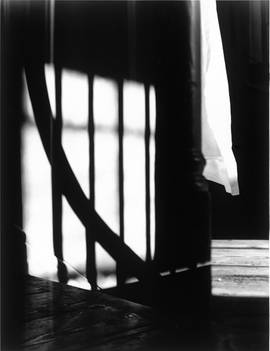

The image is Athanor by Anselm Kiefer