I have finally acquired a copy of Elisabetta Benassi’s book, All I Remember, which documents her project to collect from both public and private archives press photographs spanning the 20th century – not for the images themselves, but for the texts on the reverse, the description of what we’d be seeing if the photographs were revealed to us. The title comes from one of the photos, which depicts (so the caption tells us) the author Gertrude Stein, meeting the mayor of a French village, on the occasion of the completion of ‘a new book, dealing with the human race entitled All I Remember.’ The book was never published. And so, the absence of this book, the absence of Stein herself from our view becomes a statement for what is missing, what remains. A statement about the power of words to evoke images. We have only these lean texts to give us the narrative, and in their brevity, they act as prose poems, the shortest of stories. Here’s one from 1928, taken in Chicago:

GANG LORD PAYS ON GALLOWS

This is the fourth of five unusual pictures depicting step by step, the hanging of Charles Birger, Illinois gang lord, who was hanged in the Franklin County Jail at Benton, Ill. His hanging also marks the passing of the gallows in Illinois, which is supplanted by the electric chair. Birger is shown as the last strap is being fixed, smiling his last farewell to friends in the crowd. This picture was made just before the hood was slipped over Bergers head and shows Phil Hanna, professional executioner, standing behind him with the noose in his hand. Sheriff Pritchard asked if he was ready and the hood was slipped on just after this photo was made

or this from 1963:

BUDDHIST SUICIDE

Hue, South Vietnam: In its final moments, The blazing body of Thich Tieu Dieu writhes on the ground of the local market place as flames consume it. The 71-years-old monk was dead before this stage but contortions caused by the heat continued in the body.

I find the description of that incident even more horrific than the picture (although I’m not sure if I have seen that particular photo, there are other photos of similar self-immolations gruesomely lodged in my mind), perhaps because it is detached, unflinching (the only word that suggests the pain and terror of the scene is the verb ‘writhes’). Also, whoever wrote the description has interestingly said ‘its’ instead of ‘his’, suggesting that the body of Thich Tieu Dieu has already become an object – the subject of the photo – no longer human. ‘The body’ is dispassionate, slightly scientific. Horrible.

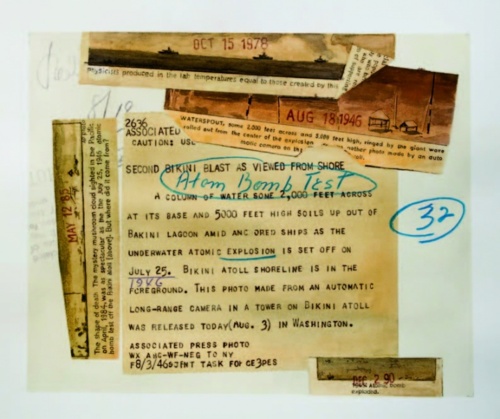

To return to the project as a whole, the irony of course is that the photo archive itself is also disappearing, an antique in the age of digital cataloguing. The texts on the photos are written by hand or typed (with the particular uneven look of old-fashioned manual typewriter lettering) and pasted to the reverse. Some of the texts are illegible with age, or the paper on which they’ve been typed is crumbling. So, Benassi has created an archive of an archive.

I don’t know why the back of a photo should be so moving, but it is. I think of the shopping bags full of photos my mother has, never properly organised into albums (although for years I’ve promised her I would), but all inscribed on the reverse in her own hand with the place, the date, and sometimes (helpfully) the subject – a way of retrieving the names of distant relatives who’ve become lost in the mists. Benassi’s project suggests that a photo is sometimes not enough on its own; it needs to be placed into a context, an occasion, an age.