We embarked for the Ness on a boat from Orford Quay early on Saturday morning. The sky was grey, the sea darker – the colour of mutton-fat jade, as in Bishop’s poem ‘The End of March’. Our group had read the poem the night before, and discussed the various endings being marked, not just the end of winter, but also the end of wanderings (thinking about the pun in the title) – Bishop had travelled the earth, but her only wish was to retire to a little house (the proto-dream-house in the poem) where she could do nothing:

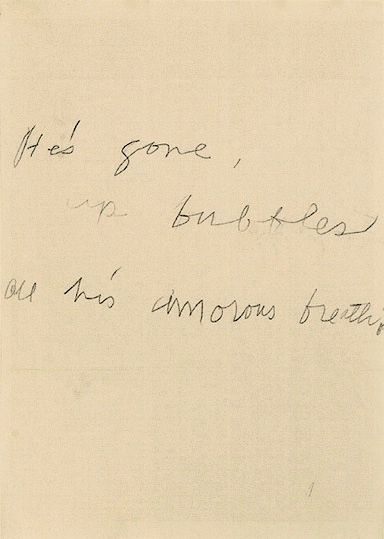

or nothing much, forever, in two bare rooms:

look through binoculars, read boring books,

old, long, long books, and write down useless notes,

talk to myself, and, on foggy days,

watch the droplets slipping, heavy with light.

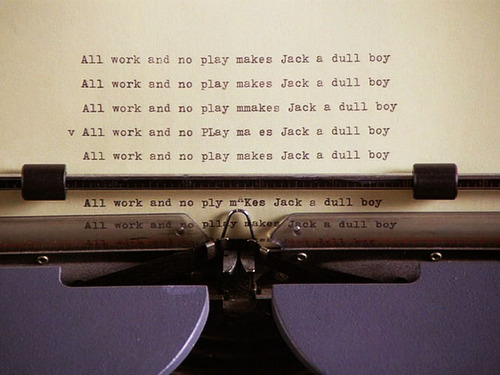

(We didn’t really believe her. That restless, active imagination of hers could never still). It is also an end of life poem – Bishop died two years after it was published. In a way it’s her version of ‘The Circus Animals’ Desertion’; a poet at the end of her career, not so much worried about the exit of imagination (as Yeats was) as almost willing her imagination to cease. How exhausting it is to always be thinking of the poem in every situation, the imagination working overtime.

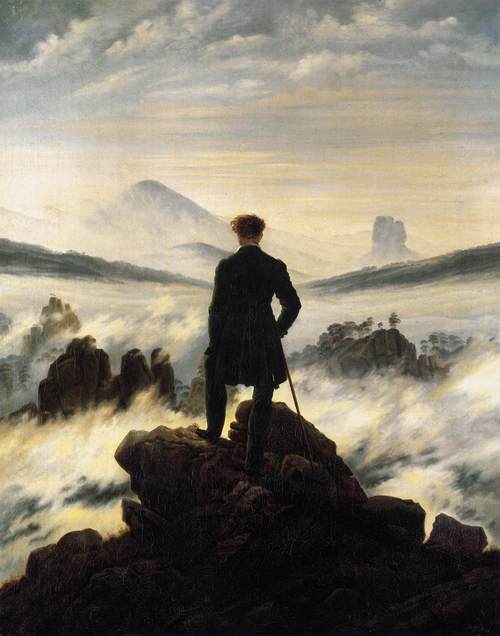

But back to the Ness, where we had come expressly to write poems. It is a place where you can’t stop the imagination from running off in all directions. It makes us question what it was like to be there in those heady secret days of code breaking and bomb making. It is a place of extraordinary contrasts: beauty and barrenness, an abundance of life amongst symbols of death, a frail ecosystem in a place that still contains unexploded ordnance.

When we arrived on the Ness, Silke, a National Trust volunteer, gave us the usual speech about staying on the paths (due to the aforementioned unexploded ordnance), where to find the information building and the toilets, but then broke into a moving and completely unrehearsed eulogy to the Trinity Lighthouse, which has stood on the Ness since 1792, and has survived storms, machine-guns and bombs, but will not survive the sea. The lighthouse will be engulfed in the next few years (in 2011, the section of the coast where the lighthouse is situated eroded by 200 meters). It has already been decommissioned, its light turned off, its mercury removed. Another ending. Silke suggested we all go and hug it one last time.

Before we took off to explore, I read a passage from The Rings of Saturn, in which WG Sebald describes his arrival on the Ness:

The day was dull and oppressive, and there was so little breeze that not even the ears of the delicate quaking grass were nodding. It was as if I were passing through an undiscovered country, and I still remember that I felt, at the same time, both utterly liberated and deeply despondent. I had not a single thought in my head. With each step that I took, the emptiness within and the emptiness without grew ever greater and the silence more profound. Perhaps that was why I was frightened almost to death when a hare that had been hiding in the tufts of grass by the wayside started up, right at my feet, and shot off down the rough track before darting sideways, this way, then that, into the field. It must have been cowering there as I approached, heart pounding as it waited, until it was almost too late to get away with its life. In that very fraction of a second when its paralysed state turned into panic and flight, its fear cut right through me. I still see what occurred in that one tremulous instant with an undiminished clarity. I see the edge of the grey tarmac and every individual blade of grass, I see the hare leaping out of its hiding-place, with its ears laid back and a curiously human expression on its face that was rigid with terror and strangely divided; and in its eyes, turning to look back as it fled and almost popping out of its head with fright, I see myself, become one with it. Not till half-an-hour later, when I reached the broad dyke that separates the grass expanse from the pebble bank that slopes to the shoreline, did the blood cease its clamour in my veins.

These days, now that the Ness has reinvented itself as a nature reserve, that sense of fear that Sebald describes has perhaps dissipated. Midas Dekkers talks about the ‘benevolent silence’ that reigns over military ruins. Is that sense of benevolence more relief on our part that this place has passed into peace? Or are some places always tainted by association, the very earth poisoned by the associations of its past (on the Ness, this is a literal tainting, if we consider the undiscovered bombs that may lie just below the surface)? Sebald gets this – he could never really go anywhere without excavating the layers of the place and finding all the glittery trash of history and memory. And now the Natural Trust, who acquired the Ness in 1993, operate a policy of ‘controlled ruination’, which is why the lighthouse is being allowed to fall into the sea. Christopher Woodward writes about this in his book In Ruins. Apparently, the NT originally thought to demolish the bunkers and sheds:

It was Jeremy Musson, an architectural historian working for the Trust at the time, who first argued their value as ruins. The Ness of shifting shingle, he said, was a palimpsest of twentieth-century history, from the wooden huts of the First World War to the Cold War’s Pagodas. In a new and hopefully more peaceful century the ruins would crumble into extinction in exposure to the wind and waves, as if the earth was being purified by Nature.

I guess if Sebald were still with us he might argue against the possibility of the last statement. It is true that Woodward’s book was published before September 11th and the new wars of the 21st century in which destruction is orchestrated largely by computers. And even Nature has turned against us, in a way, with the threat of Global Warming and ecological crisis. So maybe Sebald was right to embrace fear.

Later, after we returned to Mendham Mill, the well-manicured and picture-pretty birthplace of Sir Alfred Munnings (you couldn’t imagine a greater contrast to the landscape of the Ness), we read poems about ‘secret landscapes’ and ruin. I chose Derek Mahon’s ‘A Disused Shed in Co. Wexford’, written in the 70s, around the time that the MoD was clearing out of the Ness, and Northern Ireland was at the height of the Troubles. I have mentioned this poem before on Invective, loaded as it is with all the terrors of the century in which I was born. It’s worth quoting the whole poem, but I’ve found this, a recording of the poem read beautifully by Kevin Porter:

http://soundcloud.com/poemsbyheart/a-disused-shed-in-co-wexford

Hugh Haughton writes of Mahon’s poem:

it remains a haunting instance of the way a forgotten place — not an archaic, pre-historic place but a modern place full of historical rubbish — might become a place where thought might grow. The site of a new kind of poetics of commemoration.

Haughton could so easily be writing about the Ness in that passage, ‘a modern place full of historical rubbish’. But it’s Sebald I will finish on, as no one has written so meaningfully and so articulately about what it is like to stand on Orford Ness, with that huge sky lowering, and think about how it came to be:

My sense of being on ground intended for purposes transcending the profane was heightened by a number of buildings that resembled temples or pagodas, which seemed quite out of place in these military installations. But the closer I came to these ruins, the more any notion of a mysterious isle of the dead receded, and the more I imagined myself amidst the remains of our own civilization after its extinction in some future catastrophe. To me too, as for some latter-day stranger ignorant of the nature of our society wandering about among heaps of scrap metal and defunct machinery, the beings who had once lived and worked here were an enigma, as was the purpose of the primitive contraptions and fittings inside the bunkers, the iron rails under the ceilings, the hooks on the still partially tiled walls, the showerheads the size of plates, the ramps and the soakaways. Where and in what time I truly was that day at Orfordness I cannot say, even now as I write these words.

More images and poems from the weekend at Orford Ness will be posted on the Mendham Writers site. My thanks to Rochelle Scholar at Medham Writers: http://mendham-writers.com/news/