I start the new year enjoying the sound of poems (always in tandem with thinking about how they look on the page, of course), how they enter ear and brain through being spoken and received. This consideration of the music of words comes from a pleasant conflation of events – my recent performances of Formerly with musician Douglas Benford; a great evening with the visiting American poet DA Powell (with equally terrific turns from Amy Key and John McCullough); a fabulous reading in Dorset, participating with fellow poets Tim Cumming, Annie Freud and Bethany Pope; and my attendance at last night’s TS Eliot Prize event. These readings and performances have coincided with a recording session of my first workshop as MP3 download: watch this space for more on that in the next few weeks.

Listening to other poets read their work is always a valuable experience – there are issues of pace and voice and cadence that can only be understood by hearing a poem in its composer’s voice. I was thinking of that the last time I heard Paul Muldoon – I find his work is best read aloud to get the extraordinary richness of his word play, but my flat American vowels can never quite do justice to his Irish lilt. We are lucky to have resources such as the Poetry Archive, which brings together recordings of some of the best living poets, but also those who are no longer with us. I regret never seeing Ted Hughes read his work, but his poems come to life for me in being able to hear him.

http://www.poetryarchive.org/poetryarchive/singlePoet.do?poetId=7078

Someone asked me if performing with Douglas, who has created an urban soundscape for the Formerly poems, alters the way I read. Invariably, Douglas’s rhythms change my own, and I find myself falling into the patterns of the soundtrack, but the soundtrack has also been created from listening to the poems, so the two complement each other.

http://www.youtube.com/channel/UCP6XsQQ4Yj3kKve1gPvyAFg

I’m sure working with him has made me bolder as a performer; I think of people like Patti Smith or Laurie Anderson who are constantly working in the space between music and words – I wish I were as amazing as either one of them, but they are certainly inspirational in showing me how it can be done. Then there are those extraordinary poets such as Paul Dutton, for whom the boundary between music and word merges, and an orchestra can be created from a human mouth.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zCaCHyj4ozk

Over the years, I’ve given much thought to how to present poems to an audience. A live reading is inevitably a very different experience than reading from a book or composing, as both of those are intimate and largely silent (although, as I’ve said above, sometimes speaking poems aloud helps me hear and comprehend, both in reading the work of others and composing my own). An audience is a dynamic structure, sometimes responding back to what a poet gives them; there’s such a thing as a poetry hum or sigh, which an audience emits if a poem pleases them. The beats many years ago used to click or snap their fingers, and sometimes if a poem is a real show-stopper, a round of applause is in order (although I feel poetry readings are like classical concerts, and it never feels quite right to me to applaud between poems!). There is also the vexed question as to whether poets should provide a bit of talk or banter or explanation between poems. As long as it doesn’t overpower or interrupt the actual work, I like it when a poet ‘talks’ to the audience. As a writer, I have always thought that I am a split personality – my writing isn’t necessarily like my speaking, and the way I order my words is a different experience than the way I tell a story when I’m just talking casually. Talking between poems is a way of connecting, a way of introducing not just the poems by oneself to an audience, and so an integral part of a reading, just as choosing what poems to read for each occasion (and selecting a pair of earrings of course. The American poet Tess Gallagher once said to me that it is crucial to wear ‘statement’ jewellery when doing a reading – I think she was wearing a stunning Native American necklace of silver and turquoise at the time – so that the audience has something to look at apart from face and book).

I often wonder if the reading the finalists give the night before has any bearing on the results of the Eliot prize. There were some fine readings last night (and a few jokes between poems too), so I’ll be interested to see what the result is when they award the prize this evening.

Picture is from Janet Cardiff’s installation Forty Part Motet.

I end with an image by Jasper Johns. Invective will take a short break for the holidays. The next post will be in the new year, assuming we survive tomorrow …

I end with an image by Jasper Johns. Invective will take a short break for the holidays. The next post will be in the new year, assuming we survive tomorrow …

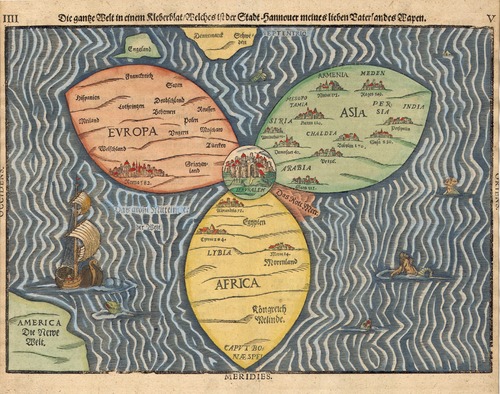

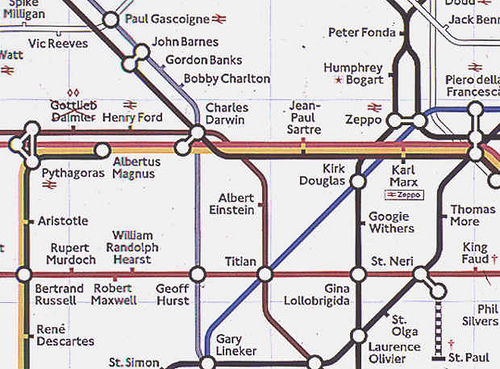

Formerly is an attempt to erect some unofficial blue plaques. The exhibition is looking lovely in its spot high over the Thames in the Poetry Library. From next week, we will be inviting visitors to create their own psychogeographical texts, based on their own wanderings, their personal maps. Watch this space.

Formerly is an attempt to erect some unofficial blue plaques. The exhibition is looking lovely in its spot high over the Thames in the Poetry Library. From next week, we will be inviting visitors to create their own psychogeographical texts, based on their own wanderings, their personal maps. Watch this space.